At about nine o’clock on the morning of September 11, 1973, Beatriz Allende, the daughter of Socialist President Salvador Allende, arrived with her younger sister Isabel at the Chilean presidential palace in the heart of downtown Santiago.[1] The military coup that would end her father’s presidency, and Chile’s dream of a peaceful revolution, had begun around dawn that day. Though seven months pregnant at the time, Beatriz had come to join forces with the presidential bodyguard to defend, by force of arms if necessary, the legitimate presidency of her father and her country’s democratic transition to socialism.

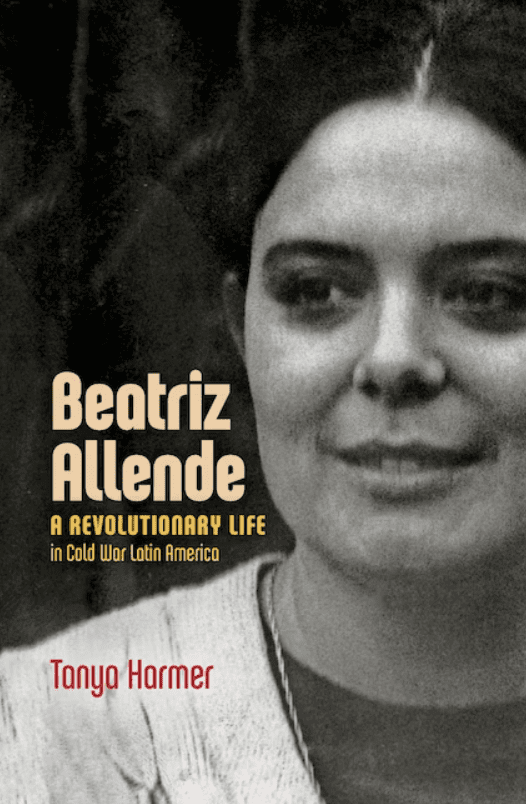

Beatriz had acted as her father’s right hand on the executive team since he took office. But in recent months, as signs of an imminent overthrow became clear, President Allende had begun to pull his daughter back from the political front lines in order to protect her. That morning, in spite of her resistance, he ordered Beatriz to leave, along with her sister and five other women. In the words of Tanya Harmer, author of Beatriz Allende: A Revolutionary Life in Cold War Latin America, Allende’s effort to shield his daughter from the impending attack “amounted to an act of betrayal from the person Beatriz loved most,” and he did it “because she was a woman” (212). Harmer’s recent monograph provides serious readers of history with a riveting close-up of how Chileans experienced their revolutionary years, focused especially on how leftist longings for a more just and equitable society challenged culturally-determined presuppositions. Like Harmer’s acclaimed masterwork, Allende’s Chile and the Interamerican Cold War (2011), this book prioritizes local agency and conflict over international interference to show how Chileans struggled to define their own history.

The primary subject of this volume, Beatriz Allende, shines in public memory as Allende’s favorite child, the middle daughter who became the son he never had. Educated in revolutionary politics from an early age, Beatriz followed in her father’s footsteps, first into the medical profession and then into Socialist Party militance. Though not outright wealthy, the family belonged to Chile’s comfortable intellectual middle class. They vacationed at the upscale seaside town of Algarrobo and, like any Chileans of means, they had domestic servants who did all their cooking and cleaning. The Allende clan could not be called armchair socialists, by any means, but they did not actually belong to the masses of working poor their political cause championed.

As a medical student at the University of Concepción, Beatriz grew close to the Enríquez brothers, Luciano Cruz, and Bautista Van Schouwen. Together with Beatriz’s first cousin, Andrés Pascal, they would become founding members of Chile’s most radical leftist organization, the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, usually remembered by its acronym, MIR. After some training in Cuba, and in opposition to her father’s lifelong commitment to the peaceful road to socialism, Beatriz embraced MIR’s option for armed insurrection as the only path to a meaningful revolution. She never made the switch to MIR, instead acting as a permanent go-between, informally linking MIR with Salvador Allende’s leftist coalition. In 1967, she did become a part of a very secret armed faction of the Socialist Party, called Organa, that mobilized in support of Bolivia’s ELN—Ejército de Liberación Nacional—as it attempted, in vain, to revive Che Guevara’s ill-fated insurrection there. Committed to actual armed participation, she found that the elenos (as ELN members styled themselves) protected her, partly because she was a woman, but mostly because she was Salvador Allende’s daughter and more valuable to their cause if she managed to stay alive.

Beatriz married a Cuban intelligence agent, Luis Fernández Oña, in 1970. Through him, she had already become a backchannel liaison between Allende’s coalition and the Cuban high command. After the coup in 1973, Beatriz fled to Cuba with her husband. She had her second child in Cuba, and she found herself thrust into a very public role, representing the exiled Chilean left, and the many victims of the military dictatorship back home. As the government of General Augusto Pinochet became an international pariah, Beatriz became an international celebrity, but it was not a role she wanted.

Though fascinated by Cuba, Beatriz found no peace there. Cuban authorities detained Loti, her long-time housekeeper—who had been caught in a lesbian relationship—and sent her off for reeducation. Fidel’s revolution considered homosexuality, and even feminism, to be capitalist vices that would naturally fade away in the socialist utopia of tomorrow. Moreover, classless revolutionary Cuba could offer no replacement for Loti. As a consequence, in her early thirties, with her fine medical training and her unfulfilled revolutionary aspirations, Beatriz Allende found herself isolated in a foreign land, facing the unknown challenge of traditional feminine domesticity for the first time (249). To make matters worse, news of the assassinations of former comrades, including Miguel Enríquez and Orlando Letelier, began to trickle in, making Beatriz feel increasingly helpless. That fatal combination drove her into a severe depression. She died by her own hand in 1977.

While Harmer’s work is rich in personal details and human drama, she did not set out to write a biography. Her study focuses on the catalytic agency of an extraordinary person pivotally situated in the unfolding of many previously untold historical connections. In the process, she reveals many previously unrecounted historical connections. The author’s sensitivity to the particularities of Chilean revolutionary culture is unparalleled. Elegantly written and abundantly sourced in memoirs, letters, and periodical sources—much of them from Cuba—Harmer’s skillful treatment of extensive personal interviews makes this work unique and remarkable. Harmer has created a rigorous, unbiased, but very gendered study, showing how the patriarchal patterns of even the most revolutionary movements consigned Beatriz Allende and others like her to a very particular kind of evolving agency. Ultimately, the author attributes her protagonist’s untimely demise to the internal contradictions and unviability of that gendered but revolutionary role.

Through the lens of this one conflicted revolutionary life, Harmer shines light on the many contingencies that contributed to the Chilean revolutionary phenomenon. Her study examines, for example, the growing influence of Chilean youth in the long decade of the 1960s. Compounded by the disruptions of an enormous earthquake in 1960, which united young people in massive solidarity efforts, sheer numbers, a fact that can be attributed to the post-war baby boom, made Chilean twenty-somethings a new and powerful contingent. Universities became the room where it happened. As Harmer observes, “university student numbers rose from 7,800 in 1940 to just over 20,000 in 1957, and 120,000 by 1970” (10). That university experience, as Beatriz knew it, represented a quantum leap in the political potential of the younger generation.

But even that giant leap would not be enough. In the most hopeful early days of the Popular Unity experiment, Harmer observes that “the opposition was strong and united. Indeed, the Left’s defensive measures . . . paled in comparison with the Right’s organization, resources, and propensity for violence” (196). Right wing women, as historian Margaret Power observed in her foundational study from 1998, formed the ideological bedrock of that opposition.[2] But there were left wing women, too, with unique struggles, decisive agency, and an untold story. Harmer has opened a new window on them.

Despite its many strengths as a work of multilayered analysis, the book has some flaws. One is a simple editorial failure: a propensity to reproduce grammatical and orthographic errors in the Spanish language. Población, a Chilean settlement of the urban poor, has an accent mark in the singular form. Poblaciones, in the plural, does not, but Harmer’s work consistently maintains that telltale accent mark. This kind of defect does not detract from the overall argument, nor from the English reader’s appreciation. Chilean scholars, on the other hand, ever mindful of their legalistic traditions, especially when it comes to proper Spanish grammar and spelling, may be frustrated by these minor orthographic failings.

A second misunderstanding goes deeper. The author observes that, in her mid-thirties, Beatriz didn’t even know how to fry an egg. This is by no means an overstatement, but the author leaves it at that, as if to say, it would only occur to the unjust patriarchal universe to expect that women should be frying eggs (185, 233). In making such statements, Harmer elides over the fact that an ignorance of domestic skills in Chile often revealed more about social class than about gender roles. This was especially true for the revolutionary left. What good was a revolutionary who could shoot an AK-47, but then needed to be fed by someone else at the guerrilla hideout?

Among pobladores, Chile’s shantytown dwellers, anyone who could not buy fresh bread, fry an egg and slice a tomato would be esteemed pituco—haughty or snobbish—a fish out of water. In the informal economy of extreme poverty, where women could earn cash frying the eggs uptown, their unemployed menfolk often took care of housekeeping by default. Egg frying, a fact of life for the poor, became an asset and a virtue for a true guerrilla fighter.

Harmer recognizes that with regard to gender equality, it would be “unfair to expect the Left to have adopted practices not found anywhere else in society” (14). In fact, it would be anachronistic. And Beatriz Allende never identified as a feminist, but as a revolutionary guerrilla fighter. But cultural presuppositions allotted her only a supporting role. In exile after the coup, travelling between solidarity events, she commented to a friend that she had grown tired of being “Allende’s daughter” (260). She wanted to be Tania, the legendary compañera of Che Guevara, who supposedly died fighting by his side in the Bolivian altiplano (257). Though Beatriz Allende never achieved that dream, her experience made it possible for other women to dream it, too. Her prominence helped to shape a vocabulary that, as Harmer points out, contributed to “a searing call to end gender violence” during the 2019 protests in Chile (274). That call went viral worldwide.

[1] Isabel Allende, the daughter of the President, should not be confused with her second cousin, Isabel Allende, the acclaimed author of the novel The House of the Spirits (1982).

[2] Margaret Power, Right Wing Women in Chile: Feminine Power and the Struggle Against Allende, 1964-1973 (New York: Routledge, 1998)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.