Commentators and scholars have long represented the United States as the supreme guarantor of a well-tempered international order. Today, however, agents of American international relations find themselves confronting uncertainty both at home and abroad. Nevertheless, as they navigate the uncharted waters of contemporary global politics, representatives of the United States and its international interlocutors can still look to their shared past for insight. There are lessons, some positive, some deeply negative, to be learned in the long, complex, and decidedly messy history of the United States in the world.

Produced in collaboration with the Clements Center for National Security, Not Even Past‘s “Uncharted Waters” series is bringing that history to life in detailed case studies, highlighting moments when Americans have grappled with the uncertainties of power. Our aim is to document unease and confusion, hidden dangers and unexpected opportunities. In so doing, we will provide readers with a fresh and provocative perspective on the history of American foreign relations.

With an eye toward the 1960 presidential election, then-senator John F. Kennedy delivered a speech in 1959 describing “the Chinese word ‘crisis’ (危机) [as being] composed of two characters – one represents danger and one represents opportunity.” Kennedy’s command of Mandarin proved, however, as imperfect as his grasp of German (“Ich bin ein Berliner”). Many scholars have identified inaccuracies in his interpretation of 危机 (wēi jī). Although Kennedy’s translation was erroneous, it did suggest how crises can simultaneously present both grave dangers and unanticipated opportunities for change.

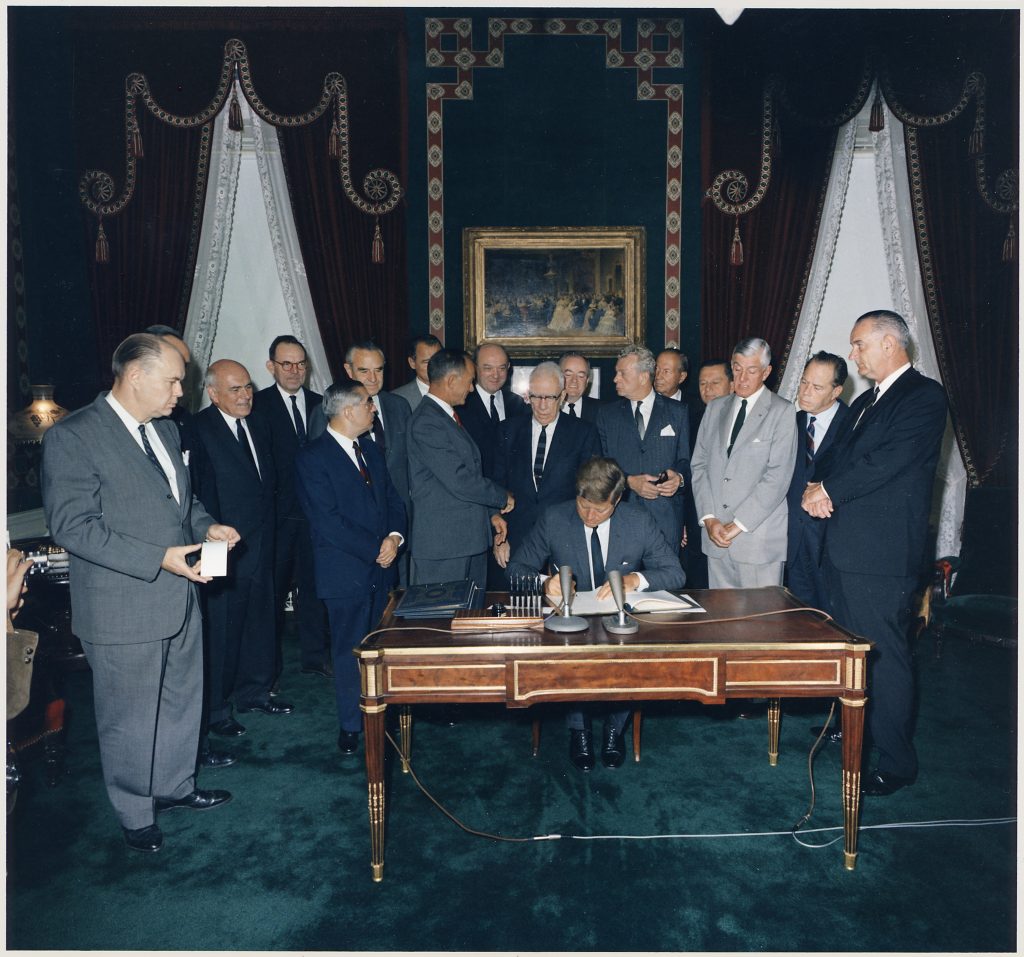

A few years later, in the fall of 1962, President Kennedy faced just such a double-edged crisis when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev deployed nuclear missiles to Cuba. The ensuing showdown took the US and the USSR to the edge of a nuclear exchange with an alarming potential for damaging escalation. Indeed, the risk for inadvertent escalation was even higher than US policymakers at the time realized, as over a hundred tactical nuclear missiles had already arrived in Cuba but were not detected by US intelligence.[1] Yet this unnerving incident also provided the impetus for a series of crisis management measures and arms control agreements over the ensuing decade that dramatically reduced the risk of nuclear war between the Cold War rivals. The following year, the “hotline” link was established by bilateral treaty and both the US and USSR signed off on the Partial Test Ban Treaty. Talks over the latter part of the 1960s eventually yielded the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty.[2] These steps signaled a new era of engagement between the Cold War rivals on nuclear issues even as their broader strategic rivalry persisted.

At first glance, the Soviet decision to deploy missiles to Cuba and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine appear as very different developments separated by sixty years and a drastically different geopolitical environment. However, a closer look reveals how a thoughtful understanding of the Cuban Missile Crisis, its context, and its aftermath can inform US responses to the ongoing upheaval in Ukraine and prepare for a postwar period that may present an opportunity for détente.

The current conflict in Ukraine reflects the continued deterioration of Russo-American relations. The two countries have grown increasingly at odds with each other across a host of issues ranging from NATO expansion to the Syrian Civil War. Moments of agreement – such as concluding the New START Treaty – have been few and far between. The demise of several landmark arms control agreements and the frostiness of US-Russia relations has led some to wistfully bid “farewell to arms . . . control.”

Similarly, the Cuban Missile Crisis marked the culmination of a series of confrontations, including an intensifying showdown over Berlin, the downing of a U-2 spy plane, and the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion, all of which occurred during the final years of the Eisenhower administration and early months of Kennedy’s presidency. Any observer of the deepening Cold War in the fall of 1962 would have had little reason for optimism for arms control or productive diplomacy, especially as news broke that the US had detected Soviet nuclear armed missiles destined for Cuba.

Putin’s nuclear threats in Ukraine and stern US warnings against using these weapons suggests the likelihood for a nuclear exchange between the US and Russia is higher than at any point since the Cuban Missile Crisis.[3] In light of this, the prospects for productive diplomacy between the US and Russian Federation appear equally bleak. However, moments in which the threat of nuclear war loom largest have historically served to catalyze critical moves towards arms control. To adapt an old aphorism, “Nothing so sharpens the mind as the sight of the nuclear gallows.”

This is not a call for naïve optimism but rather a measured reflection on patterns that may reproduce similar progress. Crucially, an overarching sense of pessimism about Russo-American relations must not preclude continued preparation for engagement on specific questions of nuclear risk reduction. On this point, several steps taken on the margins before and after the crisis in Cuba are instructive.

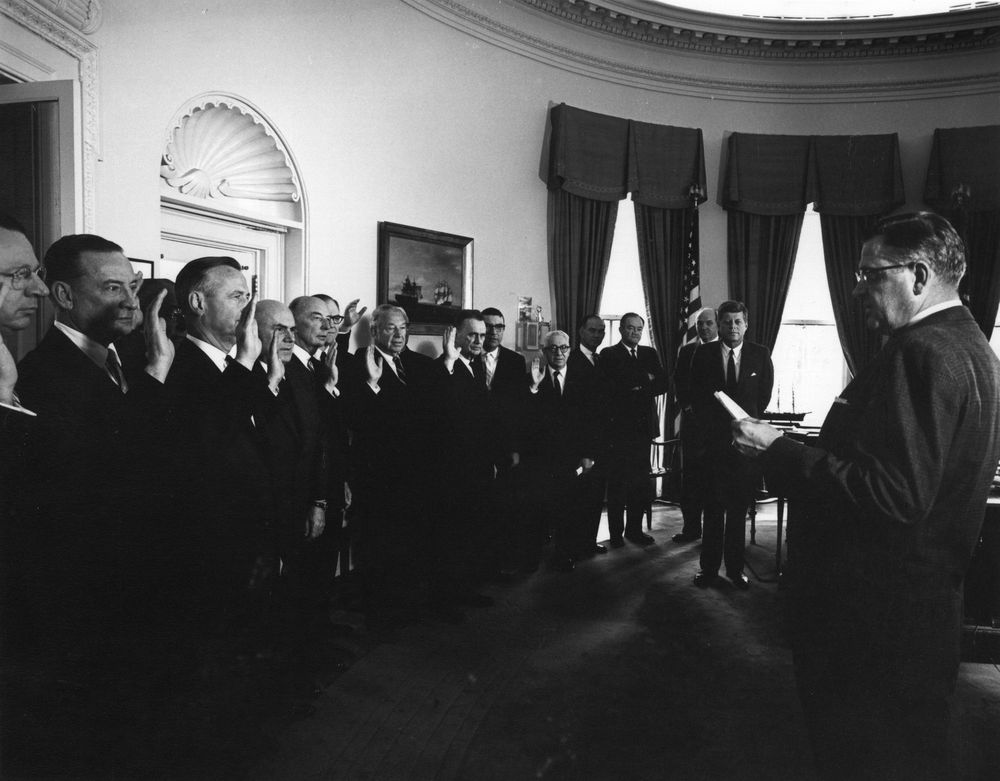

The transition between the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations marked a moribund period of negotiations on a nuclear test ban or other arms control measures with the Soviet Union. However, despite prolonged deadlock on these issues, the Kennedy administration bolstered its commitment to arms control by supporting the creation of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA) in September 1961. Even as talks in Geneva reached an apparent stalemate, ACDA spearheaded research on how to streamline an inspection regime to verify compliance with a ban on nuclear weapons tests. Furthermore, ACDA helped delineate a proposal for a limited test ban verified without on-site inspections.[4]

ACDA’s work on this issue informed a shift in the US position that overcame the impasse on inspection that had stymied years of negotiations. In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee William C. Foster, director of ACDA, pointed to this work as reason for optimism that “various steps on [arms control] may be negotiable in the foreseeable future.”[5] In the window of opportunity opened after the missile crisis, ACDA’s proposals served as the basis for the Partial Test Ban Treaty reached in August 1963. Although a large gap stands between US and Russian positions on thorny arms control questions today, continuing similar work to bridge this divide may yield dividends in discussions after the current standoff between Russia and the West.

The situation in Ukraine remains dire and its outcome uncertain. If recent Ukrainian advances continue to erode Russia’s grip on captured territory, pressure on Putin and his political cabal will continue to mount on multiple fronts. An imperiled Putin may take increasingly desperate measures, including breaking the nuclear taboo. Implicit in Kennedy’s conception of a crisis is a need to first mitigate dangers before taking advantage of any opportunities present afterward.

To reduce the risk of a dangerous escalation with Russia, the US and Western allies will have to walk a difficult tightrope, providing support to Ukraine while stopping short of becoming co-combatants. Balancing competing interests of countering Russia with alleviating economic pain caused by the disruptions to the global energy trade will only grow more challenging. However, successfully navigating these dangerous days may in fact serve to reinvigorate the listless prospects for arms control at present. Even if the broader relationship between Russia and the West remains frigid, there is some reason for optimism that Putin’s reckless nuclear saber rattling will in time lead to steps to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons.

Like Khrushchev during the fall of 1962, Putin is operating from a position of weakness. Whereas Khrushchev faced a strategic deficit in the form of massive missile gap, Putin’s aggression in Ukraine seeks to reverse the westward drift of a country that he envisions as a core component of a reconstituted Russian empire.[6] Battlefield defeats have been damaging enough, leading the Kremlin to announce a partial mobilization to try to reinforce troops in the field and reverse recent losses. The mobilization has ignited fierce opposition to the war among a populace that had thus far been largely indifferent to Putin’s supposed “special operation.” Hundreds of thousands of potential conscripts have fled Russia and thousands have taken to the street to protest the war.

Reaching the very brink of nuclear war in October 1962 jolted Khrushchev and Kennedy to take steps to improve communication and restart stalled negotiations on a test ban treaty. Although we cannot know, a similar experience may prove sobering for Putin as well and bring Russia back to the negotiating table on arms control. Chastened by military defeats and under attack at home, a weakened Putin may be obliged to make concessions in search of stability to allow him to remain in power. Furthermore, if the massive Russian stockpile of nuclear weapons fails to secure battlefield victories in Ukraine, Putin may be more willing to negotiate limits on non-strategic nuclear weapons as a follow-on to New START.

Admittedly, Putin’s previous actions suggest the chances for such an epiphany are remote. Indeed, the more promising avenue for arms control may be a post-Putin Russia, a prospect that seems more plausible today than even a few months or even weeks ago. Back in 1964 Khrushchev’s apparent capitulation to Kennedy, his erratic behavior, and waning popularity led to his removal by his own proteges in a Kremlin coup.[7] Likewise, Putin’s recent rash actions have shaken his authority. While trying to forecast exactly when and how Putin might lose power is impossible, preparing for how to engage with a prospective successor regime is imperative.

Following Khrushchev’s ouster the Johnson administration saw an opportunity to improve relations with the Soviet Union. The administration reflected at length on US-Soviet relations and tried to identify essential trends in Soviet society that shaped the Kremlin’s behavior.[8] Steps taken in both Washington and Moscow helped to pave the way for the détente that characterized the next decade of superpower relations. This episode shows how successful diplomacy requires both a keen memory and historical sensibility alongside a discerning ability to discard past grudges and grievances. US policymakers would be wise to borrow from the Johnson administration’s playbook in negotiating a post-Putin transition of power – regardless of what form it takes.

At present, the ongoing war in Ukraine will continue to

require careful crisis management, especially to reduce the dangers of nuclear

escalation threatened by Putin in recent days. Still, the crisis may also

afford opportunities analogous to previous confrontations between the Soviet

Union and the West. Capitalizing on such an opportunity to revitalize arms

control negotiations will require foresight and planning by the US and its

allies. While the transition to a new Russian government –if it happens – may

not rapidly thaw relations, it may – at the very least – open space for

conversations to reduce risk and begin reintroducing confidence-building

measures that have served as a bedrock for earlier arms control regimes.

[1] Graham Allison, “The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50,” Foreign Affairs (August 2012), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/cuba/2012-07-01/cuban-missile-crisis-50.

[2] “Castro Says Cuban Missile Crisis Helped Generate Detente,” The New York Times, February 17, 1985, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/17/world/castro-says-cuban-missile-crisis-helped-generate-detente.html; Brian White, “The Concept of Detente,” Review of International Studies 7, no. 3 (1981): 165; C Lalengkima, “The Role Of Crises In The Arms Control Process: A Lesson for India and Pakistan,” World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 17, no. 1 (2013): 108–23.

[3] Many scholars and commentators have pointed to NATO’s Able Archer 83 as another instance which almost inadvertently triggered nuclear war. However, subsequently declassified documents have shown that Warsaw Pact leaders did not seriously consider this exercise a likely cover for a NATO nuclear first strike. For a more detailed discussion of this debate, see Simon Miles, “The War Scare That Wasn’t: Able Archer 83 and the Myths of the Second Cold War,” Journal of Cold War Studies 22, no. 3 (2020): 86–118.

[4] “Arms Control and Disarmament – Hearings Before the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services United States Senate” (Washington D.C.: US Government Printing Office, September 17, 1962), 5–6.

[5] “Arms Control and Disarmament,” 8.

[6] Brian Beedham, “Cuba and the Balance of Power,” The World Today 19, no. 1 (1963): 38.

[7] Simon Miles, “Envisioning Détente: The Johnson Administration and the October 1964 Khrushchev Ouster,” Diplomatic History 40, no. 4 (2016): 726–32.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.