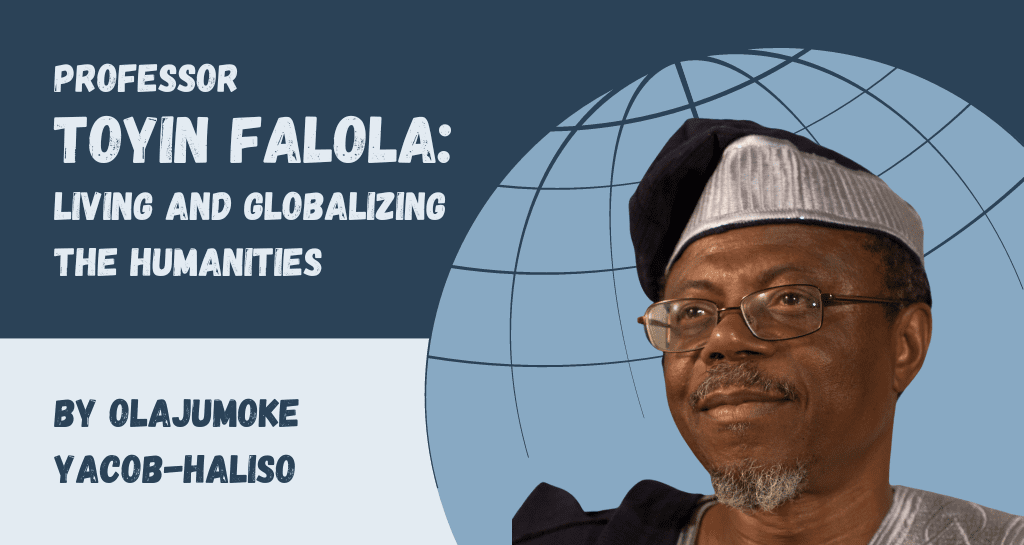

On Tuesday, October 11, 2022, at State House, Abuja, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari conferred one of the nation’s oldest and highest merit honors, the Member of the Order of the Niger (MON), on University of Texas at Austin professor of history, Toyin Falola. Professor Falola is University Distinguished Teaching Professor and Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities at UT Austin. Falola is also one of the foremost humanities scholars today. As Africa’s most decorated and celebrated academic at home and abroad, with over thirty lifetime achievement awards, sixteen honorary doctorates, eight festschriftens in his honor, seven teaching awards, three chieftaincy titles, book awards named after him and several honorary conferences, Falola is at home with achievements, accolades, awards, and unparalleled distinction.

Last year, on November 17, 2021, Nigeria’s premier university, the University of Ibadan, awarded an academic Doctor of Letters (D. Litt.) degree to Dr Falola, exactly 40 years after the award of his PhD by the University of Ife in 1981. The University of Ibadan is the first African academic institution ever to award the academic D. Litt., an epochal event, and to none more deserving than to such a distinguished global humanities scholar. Falola is a teacher of teachers, a mentor of mentors, an academic leader, astute administrator, writer, poet, polymath, and, without doubt, a far-ranging genius. These recent conferrals provide, therefore, a good occasion to recognize and reflect yet again on his towering contributions to the academy and global scholarship.

Falola is the preeminent African-born academic of our times, with a sprawling breadth of publications and contributions unrestrained by disciplinary boundaries, transcending all the traditional fields of the humanities and social sciences combined and covering a truly global geographical and cultural scope. It is a somewhat daunting task for anyone to attempt to distill and parse his oeuvre, which comprises so many published books—thirteen in the last year alone, hundreds of journal articles, book chapters and essays, countless keynotes and distinguished lectures delivered in countries on every continent, and so much more. In this age of renascent intellectual and activist movements to decenter hegemonic knowledge and reinscribe the contributions, experiences, and perspectives of non-Western and Global South peoples within entrenched knowledge production systems, Falola’s body of work is pioneering, even prescient, and is a compass for what it means to truly achieve the knowledge transformation aims of this movement. While the humanities have been criticized as partial and incomplete, having been built on an essential image of Man and humanity that is discernably western, Falola’s work boldly destabilizes established canons, consolidates knowledge from the margins, centers these within mainstream theoretical, academic, and policy conversations, and ultimately globalizes the humanities. It is, quite simply, an extraordinary achievement.

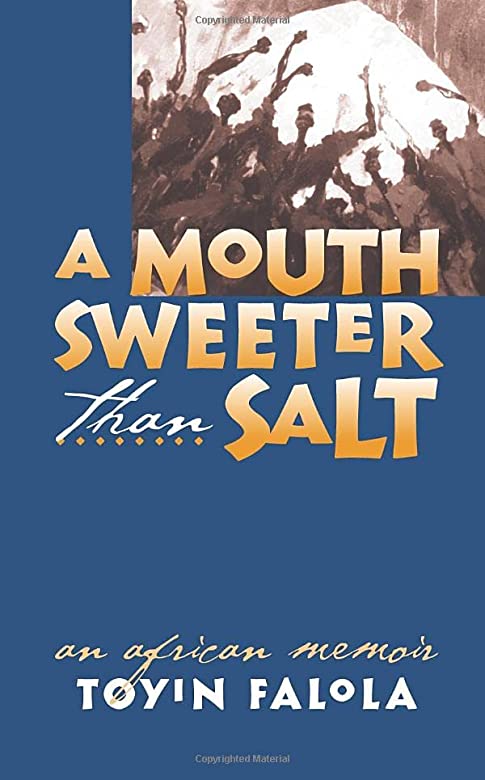

Such is his stature that Toyin Falola needs no introduction—but permit me to highlight some key biographical moments. Forty-one years ago, in 1981, he was awarded his PhD in History, completed in record time, from the prestigious University of Ife, Nigeria. What is remarkable here is his journey up to this point which marked a triumph over monumental life challenges, including childhood poverty, dropping out from high school, becoming a child street hawker, and then a self-motivated and self-sponsored student. His young years in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria, are captured in his award-winning memoir, A Mouth Sweeter than Salt, and his teenage years of drifting, in its sequel, Counting the Tiger’s Teeth. Fellow students at the University of Ife called him “indigo,” short for “indigent,” his public badge of circumstance, and yet, those fellow students, some of whom would become his colleagues as lecturers, were already calling him “prolific writer” by the time he graduated with his PhD. By all accounts, Falola was already a prodigy, having published in leading journals in the field early in his career and even before many of his teachers. This phenomenal intellectual productivity has marked his career, as has his prodigal generosity, by which he combats the demons of a difficult past.

Nigeria of the 1980s was a very troubled nation, and Falola’s story closely parallels that of the nation at this point. The monumental wealth of the oil boom of the 1970s had been squandered, while the deep fractures of a multi-ethnic nation that had fought a bitter civil war had led to the abandonment of cohesive values and the reification of a gluttonous elite that would preside over the exploitation of public office for personal and parochial gain. The 1980s would see a return to military misrule, unprecedented human rights violations perpetrated by the state, a national debt crisis, and enforcement of IMF debt conditionalities, in particular, devaluation of the naira and the imposition of structural adjustment programs which rang the death knell of social infrastructure and state welfare programs.

Prestigious Nigerian universities such as Ibadan, Ife, Nsukka and Zaria, which had debuted in the 40s and 50s at the rank of similar institutions globally were hard hit by the socioeconomic and political crises of the 80s and became part of the national decline. Many academics who refused to be coopted were hounded and arrested for their opposing views and labor union activities—including Falola. This combined with their rapid impoverishment and the deterioration of teaching and learning facilities caused many professors to take the exit option, heralding an unprecedented era of brain drain. Similar travails beset other African countries in this gloomy period of the continent’s history.

Here Falola’s path would diverge from that of his beloved nation when things fell apart at Ife and the center could no longer hold. In pursuit of a more productive academic environment for his vaulting talent, creative energy and innovative scholarship, he left Ife, first as visiting fellow at Cambridge in the UK, then York University in Canada, before finally settling at UT Austin in 1991 as a full professor of African history.

It was in this phase of his work that Falola surpassed his own established record of high-quality scholarship to join the rarefied pantheon of globally recognized scholars and thought leaders from every continent. His wide-ranging scholarship placed him at the zenith of the global academy. It made him keenly sought after from Australia to Europe and South America, and across the length and breadth of Africa and the United States. His capacious penchant for seeking out, recognizing, promoting, mentoring, supporting countless other scholars along the way, and extending compassion and hospitality to humanity in all its shades and colors would quickly turn him, literally, into an orisa, one of the gods, affectionately revered by multitudes of his protegees, friends, and colleagues.

I have refrained from pigeonholing Falola’s scholarship into any specific academic field or specialty as I firmly believe it would be diminishing to refer to him as merely an African historian. To do so would be to affirm Eurocentric assumptions of modern knowledge systems that consider Western-originated systems of thought as the center, the norm, the legitimate locus of knowledge, and all other scholarship as peripheral, liminal and merely contributory or reactive to Western thought. Contrarily, Falola’s lifelong work, overturns these assumptions in two major ways: by reshaping global knowledge systems by the breadth, depth, originality, and pluriversality of his work, and by creating his own intellectual constellations, forging alternative paths. Let me examine each in turn.

For the first pillar of intervention, reshaping global knowledge systems, the breadth of themes that have emanated from Falola’s pen bestride the disciplines of history, philosophy, international relations, cultural studies, literature, languages, the visual and performance arts, religion, politics, sociology, technology, education, and many more. He has refused to be contained within one discipline, redefining multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity in his work. He has researched African worlds, as well as those of its diaspora, flung far and wide across the globe from Europe to the Americas and beyond. But even more so must be the recognition that Falola’s work has been about humanity, in all their diversities and locations, unearthing and celebrating their unique qualities but also commonalities, rehumanizing the minimized, animalized, brutalized, and minoritized peoples of the world, uncovering and reconstructing systems of knowledge disappeared by colonial structures, interpreting subordinated cultures, probing hegemonic politics, forecasting futures.

Falola’s oeuvre actively and conscientiously rejects the notion of a universe of knowledge from which all other kinds of knowing are rendered derivative and secondary, merely the “other,” and thereby made powerless. Rather, he embraces and canvasses pluriversalism, not just as the title of one of his riveting essays but as the sum of his ontology, epistemology, and methodology. Pluriversalism maps out a world of knowing, of being, and of becoming whereby the epistemological standpoints of peoples and societies are taken as sui generis, original unto themselves, and complete, in a world of mutually existing epistemologies, a pluriverse, not an artificially hierarchized universe of ostensibly subordinate and superior systems of knowledge. In taking this path, he actively combats the epistemicide, decimation, and relegation of African and other non-Western systems of knowledge and seeks to restore them to their rightful place in society.

Falola distills these foundational ideas in several of his metatheoretical works that help us understand the hundreds of other books and essays where he presses these ideas into intellectual service in exploring varied subjects. In his 2016 lecture (now published) presented as the Kluge Chair of the Countries and Cultures of the South at the US Library of Congress, titled “Ritual Archives,” Falola shifts the ontological focus towards African texts, symbols, shrines, rituals, images, performances, art, objects, which in their agglomeration expand our knowledge of multiple bodies of philosophy, literature, languages, histories and more in our world. In this ground-breaking conceptualization, he asserts a redefinition of the central idea of the “archive” in extant historical studies to a methodological embrace of an unbounded world of data encompassing the natural and supernatural, secular and non-secular, human and non-human objects and species, dismantling the existing canon.

In his recent book, Decolonizing African Studies: Knowledge Production, Agency and Voice (University of Rochester Press, 2022), Falola takes on colonial hegemonic knowledge, as well as the decolonization and decoloniality movement. In this brilliant book, Falola demonstrates he is the doyen on global intellectual traditions and the master of the protocols of knowledge production. Falola skillfully deconstructs Western philosophies and epistemologies, dissecting how they have positioned African and Global South experiences as subaltern and silenced their voice and agency in a historical continuum that persists into the present, dominating every facet of life including development prospects. But beyond this, he does what a master does: he turns the critique inwards, explaining the failure of the decolonization and liberation movements of the last century to achieve the emancipation needed for progress, and its implications. The book provides a magisterial synthesis of diverse and divergent decolonial perspectives from across Africa and the Global South, reinstating their authority, affirming their relevance, projecting their voices, reconstructing their world, globalizing the humanities. As if this were not enough, the sequel, Decolonizing African Knowledge: Autoethnography and African Epistemologies (Cambridge University Press, 2022), unveils the mechanics and methodologies for engaging the self as an archive, and the vast pluri-disciplinary potentials of mainstreaming these subaltern methodologies into the annals of global humanities.

Importantly also, the texts described above advance a thesis of the humanities that undercuts its conservative underpinnings as a field essentially preoccupied with Western elite concerns relating to aesthetics and arcane subjects, to one that is actively bent and shaped to provide the good life by practical epistemological and policy interpolations that deliver progress and development for societies that would otherwise be left behind. His mode for doing this has been varied, from using his membership of the governing boards of universities to advocate for transformative humanities curricula and pedagogy to breaking through the barriers of conventional texts and media to initiate his own digital dialogues platform, the Toyin Falola Interviews, to facilitate the conversations that must be had.

For Falola’s second major intervention in the humanities, creating new constellations, we must understand that the majestic intellectual offerings discussed so far have not taken place in a narcissistic bubble. In personal decolonial praxis, he has actively sought to demystify, democratize, and dismantle the colonial intellectual gatekeeping that had hitherto obfuscated and denied many scholars from marginalized and precarious contexts worthy publication and academic advancement opportunities. For decades now, he has strategically created initiatives that opened up the humanities to global contributions. He founded several book series with top international presses, such as Cambridge, Palgrave, Routledge, Bloomsbury, Rowman and Littlefield, and the University of Rochester, to create avenues for the publication of a broader range of humanities scholarship than would have been possible otherwise. Presently, Falola actively manages nine book series and is substantive editor/co-editor of at least five journals while serving on the editorial board of at least five dozen others. About five years ago, he persuaded Palgrave Macmillan to establish a series of major reference texts to bring global studies of Africa up-to-date with innovative developments for another generation of scholars—and the result was twenty Palgrave Handbooks on Africa, including three on African women’s studies that I had the privilege of co-editing with him.

Not satisfied with all these pathways to enlarging humanistic studies, Falola created a consortium of African presses under the Pan-African University Press to open even more paths for subaltern voices to emerge. His annual Africa conference in Austin, has for more than twenty years served as a talent incubator that has pushed the careers of many junior scholars to stardom, including the publication of dozens of edited volumes from the conferences which started so many scholars on their publication and promotion trajectories. These efforts make Falola personally responsible for curating and producing humanistic knowledge outputs numbering in the hundreds every year, outside his own prolific writing. His constant quest for collaboration and mentorship of others on these projects have propelled many hitherto unknown scholars to shared prominence with him. A restless spirit, a courageous pathfinder, Falola exists without limits to his creativity, compassion, and optimism.

Professor Falola is the living embodiment of the loftiest objectives of humanistic studies. His extraordinary life and achievements speak to the unending capabilities of a life of the mind, of the limitless potentials inherent in all of humanity beyond borders and boundaries. Just as he has resisted the restrictive compartmentalization of humanities fields and geographies, he has personally invited and warmly welcomed colleagues from literally the entire globe as co-travelers on the academic journey. A pan-ethnic Nigerian, a true Pan-Africanist, and a global cosmopolitan, Falola is as at home in the ghettos of Lagos as in the presidential palaces in Pretoria and Lusaka. Despite his extremely lofty position in the academy, Falola can be found engaging the street trader, the lowly undergraduate, and the junior professor with the same keen interest, humility, and enthusiasm as he would royalty. And he would regularly turn the spotlight on others, extolling their achievements, as in his book, In Praise of Greatness: The Poetics of African Adulation (Carolina Academic Press, 2019), in which he deploys poetry and prose to pay homage to other scholars, artists and intellectuals for their impact and ideas, a rare phenomenon.

At UT Austin, Falola has been bestowed many major teaching awards the institution has on offer, seven of them, and he is often called upon to train teachers at other universities. Unassuming and always approachable, he goes out of his way to seek out budding talents and promising scholars, to provide opportunities for them to develop and grow, and makes the time to help them navigate the stages of climbing the academic ladder. At the same time, he finds time to advise kings and presidents, provide scholarships for needy students, share drinks with friends, and be committed to family. It is confounding how he is so deftly able to seamlessly integrate scholarship, pedagogy, mentorship, professional service, family, and community leadership.

Ultimately, on account of his generous habit of promoting and celebrating others, and returning his achievements as greater service to Africa and all of humanity, we celebrate Toyin Falola as our own, one of the best to have come out of the womb of Africa, who has fought difficult epistemic battles on our behalf and come out not just undaunted but indeed victorious. We rejoice with him. We are proud of him. Falola, rise still.

Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso is Associate Professor of African and African American Studies at Brandeis University, Massachusetts.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

This article’s banner incorporates a modified version of an image originally published on Wikimedia Commons and licensed by Creative Commons.