The author of the Gospel of John wrote that Jesus told Nicodemus “Amen, amen I say to thee, unless a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.”[1] Nicodemus responded in bewilderment, “How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother’s womb, and be born again?”[2] Elsewhere, to teach the necessity of humility, the author of the Gospel of Matthew wrote that Jesus told his disciples that “unless you be converted, and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.”[3]

The idea that one must be “born again” or become like a child to enter the kingdom of heaven has shaped Christian conceptions of conversion and spiritual development for millennia now. One scholar argues that the image of the child in early Christian texts appears as an important model “for explaining concrete qualifications for entering God’s kingdom.” That is, the “child” became a fundamental tool for imagining an ideal (adult) self.[4] This Christian image of childhood, however, is intwined with gendered conceptions of adulthood. We see this especially in the twelfth-century Cistercian conceptions of monastic maturation, as they imagined new adult recruits to mature from “children” to masculine monks.

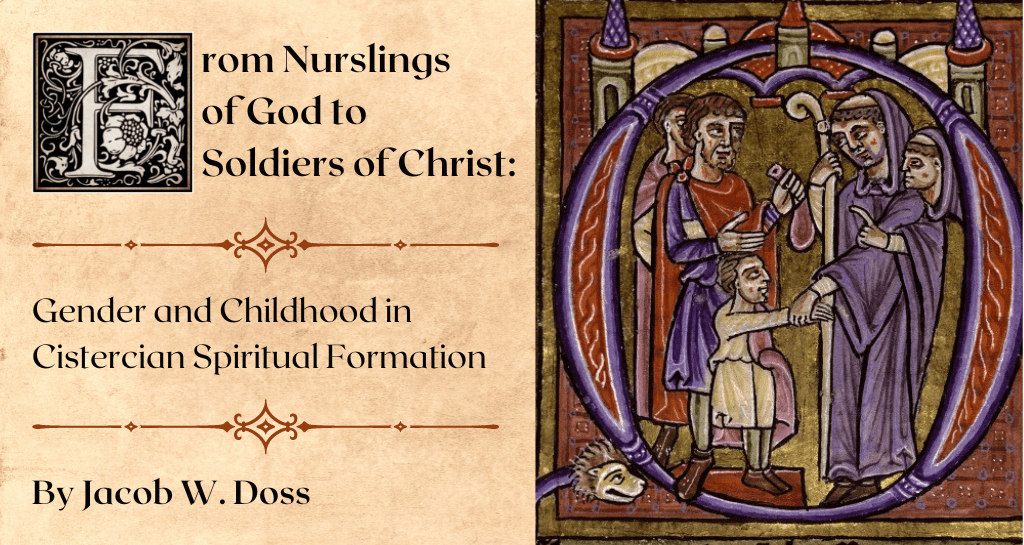

My book project, Making Monastic Men: Imagined ‘Childhood,’ Education, and Gender in Cistercian Formation, focuses on what would become the most famous and most successful new monastic group (in terms of numbers of monasteries) to spring out of the twelfth-century religious awakening, the Cistercians. The Cistercians began in 1098 when Robert of Molesmes and a group of followers left their monastery at Molesmes to start a new monastery at Cîteaux, just south of Dijon in the countryside of Burgundy, France. In this new monastery they aspired to a stricter observance of the Rule of Benedict (the foremost book of precepts for monastic living at the time) than what they had previously been practicing. This upstart group would institute substantial changes from traditional monastic customs. For example, in one of the most significant departures from conventional practices, they ended the custom of child oblation in their monastery, the practice whereby parents gave up their children to monastic communities as offerings to God. By ceasing this practice and accepting only adult recruits who had made a conscious decision to convert to the monastic life, the Cistercians not only jettisoned a traditional monastic responsibility of raising children, but also removed themselves from certain feudal responsibilities that often came with accepting children.

What has generally been missing in scholarly examinations of Cistercians and gender is the ways in which Cistercian conceptions of childhood shaped how they understood their masculinity. My work examines how the traditional Christian language about childhood changed during the twelfth century within a Cistercian monastic context. With the Cistercians only accepting adult men, usually clerics, knights from the minor aristocracy, and other monks, childhood became a useful metaphor for imagining these new recruits’ place in the monastic hierarchy and for conceptualizing the extent of their monastic abilities. It was at this time that Cistercian authors merged images of “childhood” with increasingly gendered and erotic metaphors used to explain a spiritual maturation intended to culminate in the experience of mystical union with God. For medieval Cistercian monks, becoming like a child entailed the first and perhaps the most important step in the process of maturing into a masculine, battle hardened monk ready for the Jesus’ mystical bedchamber. Rather than only the specter of “woman,” Cistercians often used childhood as a foil to conceptualize an ideal Christian masculinity.

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a turbulent time that saw a ferment of religious enthusiasm, such language about the child became important for those trying to explain conversion and spiritual formation. In the midst of this period of religious enthusiasm, many Christians turned inward. With this emotional turn, medieval Christian thinkers began stressing the humanity, frailness, and emotions of Jesus and Mary in their devotions.[5] Similarly, new attitudes toward love entangled with a violent ethos emerged in the blossoming chivalric and Romance traditions. Such attitudes influenced and were influenced by Christian thinking.[6] Ecclesiastical authorities also attempted to enforce new ideals that separated the clergy from the laity, and enhanced clerical prestige. For example, many church officials made a concerted push to codify and enforce clerical celibacy and to end the buying and selling of church offices (simony).[7] In all of this, Christian authors increasingly turned to human relationships, especially those of the family, to model and conceptualize everything from church hierarchy and authority to ideal individual behavior.[8]

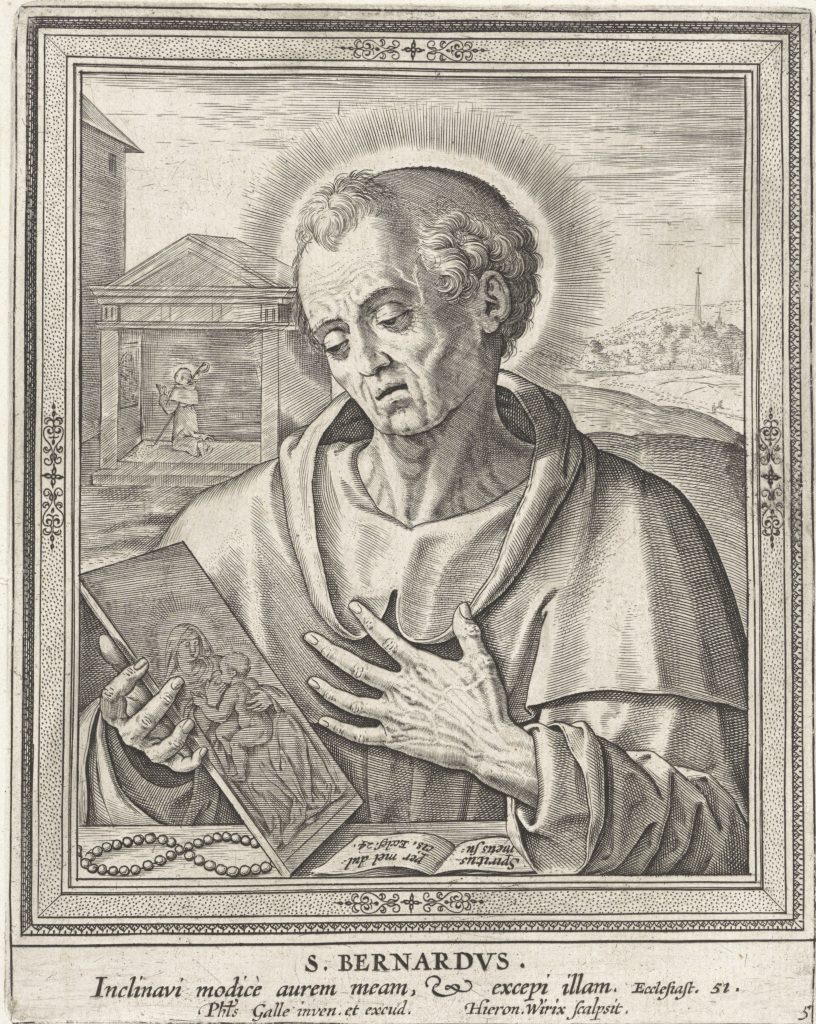

Celibate men, and especially new monastic groups, increasingly disentangled from family life and social obligations, and living in communities where they experienced few interactions with women, began re-imagining their masculinity as something flexible. Medieval Cistercians, in particular, are famous for their fluid use of gendered images. The Cistercians’ plumbed the allegorical depths of the Song of Songs, and in so doing stressed, in a more intense way than previous commentators, the individual feminine soul’s relationship to the male Christ. In this formulation the soul became the bride to Christ’s bridegroom. For example, the most famous Cistercian, Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), in his commentary on Song of Songs 1:2, affectionately expounded on the sweetness of the kiss of Christ’s mouth.[9] Cistercians also have described themselves as pregnant and nursing mothers, authoritarian fathers, brides, little girls, children, and soldiers, while teaching with images of female soldiers, both male and female prostitutes, lascivious adolescents, and virgins. In the words of Jo Ann McNamara, “Celibacy freed men from women. It enabled the clergy to use elements from both [sic] genders to construct a new model of humanity in which men could play all the roles.”[10]

To experience the ecstasy of Christ’s bed, however, Cistercians usually needed to mature in their monastic life and practice. Cistercians imagined childhood as part of their model for maturing into a masculine monk. Aelred of Rievaulx (d. 1167), in his treatise Jesus as a Boy of Twelve (c. 1160-1162), succinctly explained this when he wrote: “In order that we who by disposition are little children . . . might be born spiritually and grow up and make progress through the distinctive spiritual ages. Thus his [Jesus] bodily growth is our spiritual growth; and the things that are said of him at every age [of his life] are to urge us through each step of progress spiritually . . . . Therefore, may his bodily birth be our spiritual birth.”[11]

Aelred urged his monks to look to the childhood of Jesus as a model for their own spiritual growth. By implication, those new to the monastic life were like children who then metaphorically aged and matured as they progressed by gaining experience in their monastic practice. Elsewhere, Aelred describes this maturation as a progressive training of the feminine, childish flesh that resulted in the monk becoming rational and masculine as he learned to control his body and mind. In his work the Mirror of Charity written in 1142, which he composed for new monks, Aelred warns that when pleasure “contaminates the flesh, and effeminates the mind, whatever is honorable in the soul, whatever is beautiful, and at worst whatever is manly is equally crushed and destroyed.”[12] The Benedictine monk and, later, Cistercian convert, William of St.-Thierry (d. 1148), contrasts new recruits with mature monks by combining the language of age and gender. He suggests that the undisciplined are like the young; they are hot-blooded, have a fiery soul, are labile in their age, and full of restless curiosity. However, their opposite “possesses a manly maturity, a serious soul, [are] chaste, sober, [and] disgusted by outward things.”[13]

Bernard of Clairvaux fleshed out this idea in one of his sermons which he delivered to his monks in their daily chapter meetings. In the talk, which the medieval editors of Bernard’s sermons called “On the Various Affections or States by which the Soul is under God,” Bernard overtly explains monastic progression as maturation.[14] New converts, he says, are those “who are like little children in Christ who still long for milk, as if living under a teacher and a pedagogue.”[15] He goes on to explain that “just like children,” these novices “fear they might offend their teacher, lest they receive a beating or be cheated of a small present that that kind instructor uses to entice them.”[16]

New monks, eventually, ought to advance and mature past the need for consistent reassurance and correction. As novices became more adept at regulating and correcting themselves, everyday practices became easier, and they could turn their focus to heaven. Bernard suggests that novices, at this point, take on the status of sons of a “robust age,” the Latin robustae aetatis, conveys the masculine image of someone that is firm, solid, and, of course, robust.[17] No longer should monks be restless, easily moved to sin, or distracted. Monks of a “robust age” stand in contrast to those of the childish, “labile age” that William of St. Thierry described.

Elsewhere, Bernard explains that this maturation happens through learning to fight. By doing battle against the flesh, that is the process of learning to overcome and control one’s urges, the monk becomes a masculine warrior. In a letter to the former archbishop Malachy of Armagh (d. 1148) in Ireland, Bernard writes that two new monks were not ready to leave his monastery to return to Ireland “until the battles of the Lord are taught to these new troops by combat.”[18] In a letter to a man named Fulk, who had abandoned his vow to join a religious community known as the Canons Regular, Bernard insults Fulk’s masculinity by claiming that, in a fit of youthful vacillation, he had succumbed to the feminine urges of his flesh by fleeing to the city, duped by his uncle and attracted by the city’s lewd and luxurious enticements. Trying to convince Fulk to honor his vow, Bernard calls him an “effeminate soldier (delicate miles)” and urges him to “Take up arms, man up, while the battle still rages.” If only Fulk will do this he will come to know Christ as a comrade in arms. Bernard writes, “If Christ recognizes you in the fray, he will recognize you in heaven.”[19]

Returning to Bernard’s sermon on the soul, we find that there is a final stage in a monk’s maturation. In this stage the mature, masculine, battle hardened, virtuous monk’s soul experiences the ecstasies of Christ’s bedchamber. Bernard writes that the “whole soul proceeds into God, who is for her [the soul] the perfect and singular desire, so the king leads her into his bedchamber so that he can pull close to her and enjoy himself.”[20] Bernard sums up this progression from non-masculine child to masculine spiritual warrior, to bride and mystical lover of Christ (which Bernard insists is a rare experience for monks), succinctly in the beginning of his parable, On the Son of the King. In this short parable Bernard appeals to new Cistercian recruits using imagery they likely found familiar. He tells the salvation history of humankind using maturation, battle, and sex as analogies. He begins by saying that God made humankind his son, and gave this “delicate child” the pedagogues of the Law and Prophets until the time of his consummation.[21] The child (both a stand-in for humankind, but also presumably for new monks as well), however, like the prodigal son, succumbs to the desires of his flesh and must be rescued by the virtues. The virtues then teach him to fight the vices as part of their rescue mission. Eventually, the virtues and the boy reach Lady Wisdom’s walled city (the monastery) where Lady Wisdom meets him in the streets and whisks him off to her bed.[22]

As we have seen above, Cistercian authors used an imagined “childhood” to teach about what a mature, manly monk should be like. The image of the non-masculine “child” also shaped the ways the Cistercians thought and talked about hierarchy and authority. New recruits were like children, their seniors in the monastic life were their teachers, pedagogues, and seasoned warriors, and abbots were like fathers and mothers. Hopefully, by following their lead, the new recruit might mature into a masculine spiritual warrior fit to be a bride of Christ and experience the joys of Christ’s bed. All of these gendered articulations of monastic hierarchy, conceptions of authority, and expressions of elite practice, depend on the presence of a “child” for their analogical power.

When child oblates comprised a majority of monastic recruits, the need for maturation was apparent and experienced as a hierarchical reality in the monastery. By ending child oblation, however, Cistercians began deploying “childhood” as a powerful metaphor for adults progressing in the monastic life. In doing so, the Cistercians’ imagined the monastic “childhood” of the adult monk as a fundamental stage in their maturation into a masculine monk. The “child” became a non-masculine foil against which they defined masculinity. These metaphorical gendered formulations gained more force as monks, and later the friars, drew on them in their teaching and preaching to the laity as the papacy began stressing Christian education at the turn of the thirteenth century, thus solidifying this intwined understanding of gender and childhood in Christianity.

Jacob Doss is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Historical Studies. Before completing his Ph.D. at the University of Texas he earned his B.A. with a double major in history and anthropology and a minor in religious studies from the University of Arkansas, and his master’s in church history from Boston College. He has published in Church History and Studies in Medievalism. His current book project, Making Monastic Men: Imagined ‘Childhood,’ Education, and Gender in Cistercian Formation, examines the emergence of “childhood” as a fundamental element in medieval monastic gender ideologies. This research has been supported by the American Historical Association, The Medieval Academy of America, The American Catholic Historical Association, The Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, and the University of Texas at Austin.

[1] John 3:3 (DRA). The Greek ἄνωθεν can be translated either as born “again” or “from above” and forms the basis of Nicodemus’ misunderstanding of Jesus in the text. The Latin in the Vulgate, the language of the medieval Christian Bible, is less vague than the Greek and translates into English as “born again.” The Latin reads “Amen, amen dico tibi, nisi quis renatus fuerit denuo, non potest videre regnum Dei.” On the ambiguity of the Greek and how it works in the context of Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus, see Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (i-xii), The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.), 130.

[2] John 3:4.

[3] Matthew 18:3.

[4] Eunyung Lim, Entering God’s Kingdom (Not) Like A Little Child: Images of the Child in Matthew, 1 Corinthians, and Thomas (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021), 3, 141.

[5] See for example Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 2-7, et passim.

[6] Jean Leclercq, Monks and Love in Twelfth-Century France: Psycho-Historical Essays (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1979), 8-23.

[7] See Helen Parish, Clerical Celibacy in the West: c. 1100-1700 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010). For the eleventh and twelfth centuries, see 87-122. For the relationship between simony and monasticism see Joseph H. Lynch, Simoniacal Entry into Religious Life from 1000-1260: A Social, Economic and Legal Study (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1976).

[8] Megan McLaughlin, Sex, Gender, and Episcopal Authority in an Age of Reform, 1000-1122 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 5-15.

[9] See Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons 1-4, in Song of Songs I, trans. Kilian Walsh (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1981), 1-24. For an overview of the Cistercian mystical tradition see Brian Patrick McGuire, “Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercian Mystical Tradition,” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Christian Mysticism, ed. Julia A. Lamm (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 237-250.

[10] Jo Ann McNamara, “The Herrenfrage: The Restructuring of the Gender System, 1050–1150,” in Medieval Masculinities: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages, ed. Clare A. Lees (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 22.

[11] Aelred of Rievaulx, De Iesu puero duodenni, CCCM 1, 258-259.

[12] Aelred of Rievaulx, Speculum caritatis, CCCM 1, 43.

[13] “What are these if not the young, naturally hot-blooded, and a fiery soul, a labile age, restless curiosity; and the other possesses a manly maturity, a serious soul, chaste, sober, disgusted of outward things and as far as possible hides himself within the self?” For the Latin see William of St.-Thierry, Epistola ad fratres de Monte Dei, CCCM 88, 268.

[14] In the collected works of Bernard this is Sermo 8, SBO 6-1, 111-117. An English translation can be found in Bernard of Clairvaux, “Sermon 8,” in Bernard of Clairvaux: Monastic Sermons, trans. Daniel Griggs (Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2016), 49-57. Citations from Bernard of Clairvaux, Sancti Bernardi Opera, eds. Jean Leclercq, C.H. Talbot, and H.-M. Rochais. 8 vols. (Rome: Editiones Cistercienses, 1957-1977), will be abbreviated as SBO vol. no., pg. no.

[15] Sermo 8, SBO 6-1, 115.

[16] Sermo 8, SBO 6-1, 115.

[17] Sermo 8, SBO 6-1, 116.

[18] Epistola 341, SBO 8, 282–283.

[19] Epistola 2, SBO 7, 22.

[20] Sermo 8, SBO 6-1, 117.

[21] De filio regis, SBO 6-2, 261.

[22] De filio regis, SBO 6-2, 264-265.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.