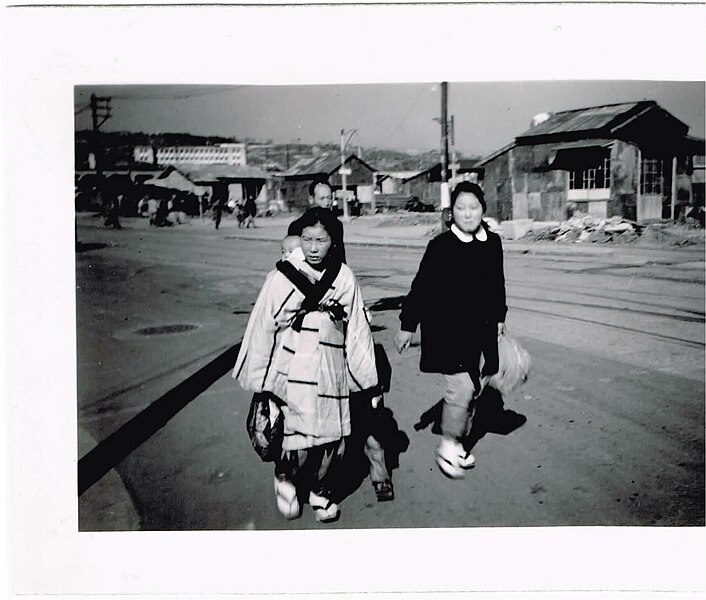

An orphaned boy and girl wander helplessly through a destroyed Japanese city toward the end of World War II. The boy, older but not old enough, has frustrating interactions with the adults they meet, most of whom are preoccupied with their own struggles to survive. Despite his earnest efforts, he cannot keep his little sister safe. He finally wanders alone into a train station full of other displaced people. The station is a literal junction but also a metaphorical one: the boy’s world ends here, but beyond it a new Japan will rise from the ashes.

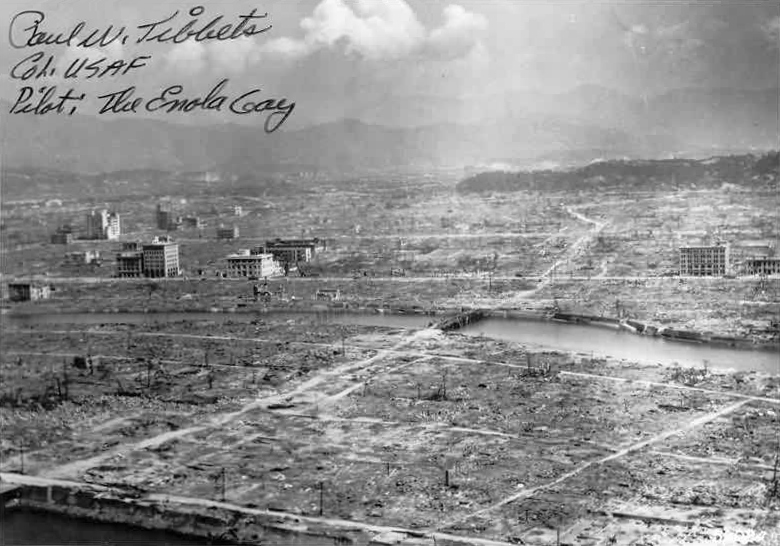

The plot briefly described above comes from Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima, a 1953 docudrama that used real survivors of the atomic bombs to bring the city’s darkest days to the big screen. From 1945 to 1952, Japanese movie studios followed the dictates of media censors in American occupation headquarters by avoiding discussion of wartime bombings, depictions of American occupation troops, and a host of other topics that Americans found uncomfortable. With the end of the occupation came a rush of bomb-themed movies, from Kaneto Shindо̄’s Children of Hiroshima (1952) to Ishirо̄ Honda’s Godzilla (1954) to Akira Kurosawa’s Record of Living Things (1955). Sekigawa’s Hiroshima, perhaps the most literal of the bunch, had little box office impact but exerted significant influence on cinema’s international New Wave movement that lay just around the corner.

It also foreshadowed a movie that the first paragraph of this piece describes equally well: 1988’s Grave of the Fireflies. When it came out 35 years after the release of Hiroshima, Grave of the Fireflies was largely forgotten outside of the cinephile community. But in the intervening years, its audience has only grown. Its Blu-Ray and streaming releases have allowed it to impact – one might say traumatize – new viewers around the world.

Fireflies is set in Kobe, not Hiroshima or Nagasaki or the even more heavily-bombed Tokyo, but it is grim enough all the same; the brother dies in a train station not long after the sister succumbs to illness. In Hiroshima, which has less finality but more overt messages for the present, the brother does not die in the station but leaves to find work in a factory until, seven years later, it begins to produce artillery for American soldiers in Korea. Unwilling to contribute to more war deaths, the young man quits and disappears into the drop-out world of pachinko gambling. He never discovers what became of his sister after they lost each other in the ruins of their childhood city, and that uncertainty underlines the movie’s message that Hiroshima’s agony is not over. As long as war goes on, nobody is safe from Hiroshima’s fate.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988) has its messages, too, though they can be harder to detect beneath the intense tragedy of its protagonists. More than the story of doomed siblings, the movie is an uncompromising critique of Japanese society in the waning months of World War II. It is also a milestone in the development of Studio Ghibli’s Japan-centric but universalist storytelling.

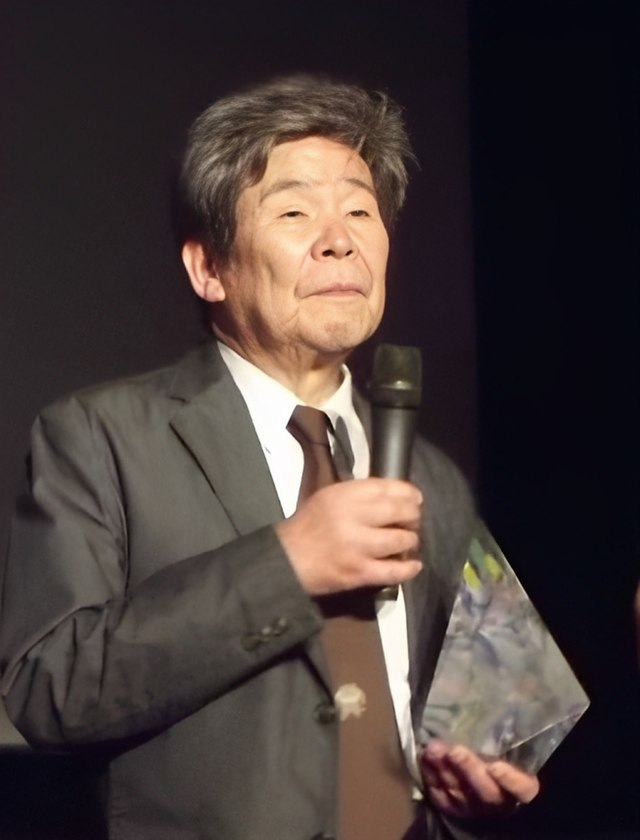

1988 was a year of firsts for the young Studio Ghibli. The studio’s creative frontman Hayao Miyazaki directed My Neighbor Totoro, his first film set in historical Japan rather than in a fantasy world. The studio did not expect Totoro to be a financial success, so it decided to package it with an adaptation of a wartime melodramatic novel titled Hotaru no Haka, or Grave of the Fireflies. Fireflies was Ghibli’s first film neither written nor directed by Miyazaki. Instead, it was helmed by longtime animator Isao Takahata, who would go on to direct other adult-oriented features like Only Yesterday (1991), My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999), and The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013).

The studio’s calculation was correct in the short term, but when Totoro aired on television – paired with the release of an adorable plushy – it found massive success. It soon became an international hit too, and Totoro’s title character is now Ghibli’s mascot and studio logo. Fireflies’ success has been quieter but also impressive. Disney, which for many years owned the foreign distribution rights to Totoro and most other Ghibli films, didn’t touch Fireflies, but the movie has received English dubs and frequent home media releases nonetheless. It appears on numerous Best Films lists and is many people’s go-to answer to the question: “What’s the saddest movie you’ve ever seen?”

Yet in many ways it cuts against the studio’s grain. Miyazaki’s renowned fantasies, Takahata’s later stories, and other Ghibli directors’ efforts are almost always characterized by capable people working toward clear-cut, laudable objectives. Not so much with Fireflies. Its protagonists, a boy named Seita and his younger sister Setsuko, think irrationally, make bad decisions, and don’t ever seem to know what they should do next. They are, in the most difficult ways, children, and they are caught up in terrible events.

This is particularly true of Seita. As the older sibling, he is responsible for the care of his sister when their mother dies in a bombing raid that destroys their house and their father is killed in battle. At first he does well enough. He finds lodging for himself and Setsuko in the home of a woman who provides them with food in exchange for their mother’s clothes. This woman embodies the attitude that, in wartime, everyone must make sacrifices for the good of the nation. The most poignant touches of visual detail in the movie come as she scrapes burnt leavings from the bottom of a cooking vessel, and when her young lodgers eat every grain of rationed rice and each infinitesimally-small crumb of candy in front of them.

Seita begins to go astray, though, both from his familial duties as a caregiver and his social duties as a Japanese citizen. He quarrels with the woman sheltering them and leaves the comparative comfort of her house. At 14 he is old enough to work, to “contribute to the war effort” as the woman commands him to do, but he opts not to seek employment at a munitions factory or other work detail. He never articulates his reasons, but it is not anti-war sentiment; Seita is as emotionally invested in the success of Japan’s imperial mission as are all of the adults he knows. Rather, he seems to be motivated by a vainglorious search for individual autonomy.

Seita takes Setsuko to an abandoned bomb shelter near a small lake outside of town. In his mind, and at first glance, this appears to be an idyllic retreat from the horrors of the war. They spend their first night there catching fireflies, delicate creatures that live a lifespan of mere days before winking out of existence. The symbolism is obvious, and it leads to the movie’s most haunting images.

It is not long, though, before it becomes clear that Seita is not equipped to handle life in exile. Setsuko develops a rash that grows increasingly painful, and she begins to exhibit the disturbing physical symptoms of malnourishment. Though Seita has some money in a bank account, he turns to stealing food, a serious and increasingly common crime during the American naval blockade of Japan. Perhaps unconsciously, in his orphanhood Seita becomes obsessed with living outside the strictures of society. The death of the four-year-old Setsuko is a consequence of that determination, and Seita himself dies homeless and starving in a dilapidated train station.

The movie is a cautionary tale about young people who recklessly buck social mores, but Seita is not portrayed as solely responsible for his and Setsuko’s deaths. In fact, he hardly seems to realize what he is doing or what is happening to them. He is a child, well-intentioned but confused and psychologically shattered. The movie reserves its moral censure for the adult characters. Director Takahata, who also wrote the screenplay, shows adults to be willfully apathetic about the children’s desperate plight. The woman who takes them in and takes their mother’s possessions as payment also drives them out with harsh criticism and justifies it as an act of patriotism. A doctor diagnoses Setsuko with malnutrition, but he refuses to give her medicine and sends the brother and sister away with no food. The worker who discovers Seita’s body in the movie’s flash-forward prologue seems unmoved, poking his and other corpses and searching their possessions before casting them aside. During the course of the movie only a police officer shows Seita some kindness when he declines to press charges for theft, but in Seita’s case it might have been a greater kindness to take him into custody. Takahata has said that Fireflies is not an anti-war film, as many of Miyazaki’s movies quite clearly are, but it is certainly a bleak portrayal of the material and social conditions that Japan faced at the end of its last great war.

Like its predecessor Hiroshima, Fireflies is tightly rooted in place and time, so why does it continue to resonate with global audiences? Hiroshima’s artistic influence, for example, on French filmmaker Alain Resnais, whose film Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) stars one of the lead actors from Sekigawa’s film, is thanks in part to the unique nature of the atomic bombings. That film’s comparative scarcity for many years also made it especially alluring for those who knew about it. Released at the other end of three decades of miraculous economic growth, Fireflies has always been readily available, and it has become something of a rite of passage for anime fans. Starting with an anonymous bombing, one of thousands of similar aerial attacks, it follows marginal lives that leave no historical record. That has increased its universal appeal. People born long after the war and on the opposite side of the globe can see themselves in Seita and Setsuko. They might have been them, if they’d been born at the wrong time and place. If all-ages Ghibli fantasies like Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) and Spirited Away (2001) work because of universalist “hero’s journey” elements, Fireflies speaks to people because its arcs are so pathetically pedestrian. Its lives, like the titular insects, are brief and leave no trace on a world that moves quickly on.

As a work of art and a piece of historical fiction set during an especially difficult era, Grave of the Fireflies is a valuable achievement. Embracing Defeat, John Dower’s 1999 Pulitzer-winning nonfiction book about early postwar Japan, would make an excellent non-fiction pairing with Fireflies. The movie is also an unconventional herald of Studio Ghibli’s turn-of-the-millennium dominance in sophisticated animated entertainment. If the recent success of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is any indication, movies that touch on Japan’s unique wartime experience – whether through well-known stories like Hiroshima’s or obscurer ones like Fireflies’ – will continue to fascinate international audiences for a long time to come.

David A. Conrad received his Ph.D. from UT Austin in 2016 and published his first book, Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan, in 2022. He is currently working on a second book, which will also focus on postwar Japan. David lived in Japan’s Miyagi prefecture for three years and can’t wait to go back to his home away from home.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.