From the editors: Since its creation, Not Even Past has published hundreds of reviews covering a wide range of periods, places and issues. In this series, we draw from our archives to suggest three great books focused broadly around a single topic. In this article, we present three fascinating and important studies related to Japan.

Our three book suggestions cover a lot of ground from John Dower’s classic examination of Japan’s experience of defeat in the years following World War II to Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci’s pioneering investigation of birth control and eugenics in Japan and the US to the rowdy and unexpected life of a Tokugawa samurai. These books showcase some of the best scholarship on Japan. Our reviews come from three wonderful scholars, David Conrad, Kellianne King and Edgar Walters who provide insightful analysis of these important studies.

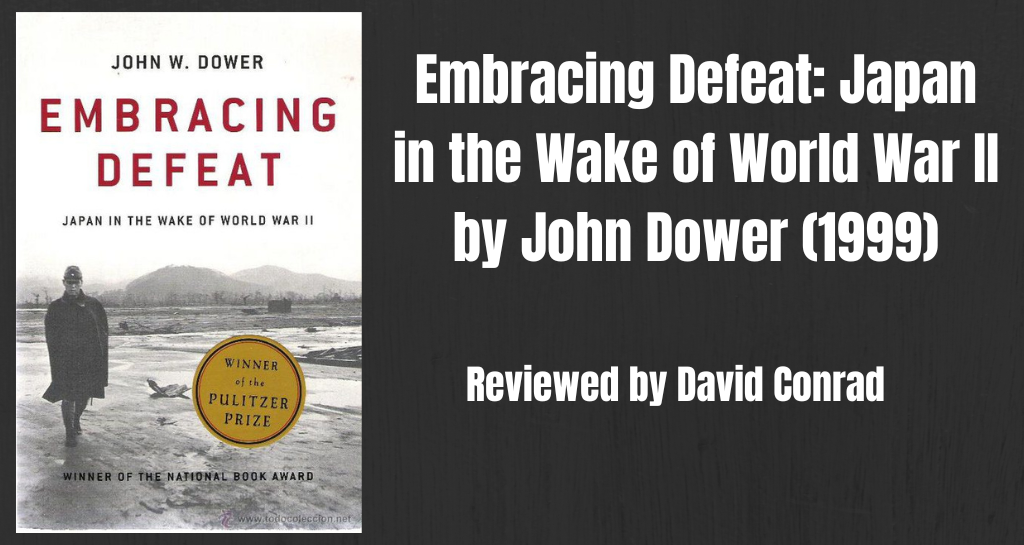

David Conrad writes:

“Dower sets out to convey “some sense of the Japanese experience of defeat by focusing on social and cultural developments. . . at all levels of society.” Initially, the bitter reality that their exhausting war had ended in defeat proved profoundly demoralizing for many Japanese citizens. Dower’s portrayal of the shantytowns of bombed-out Tokyo provides poignant evidence of the impoverished condition in which many Japanese found themselves at war’s end. But as Japan embarked on its long occupation interlude, its citizens seized opportunities to start over, rebuild, and redefine their nation. Defeat became a creative process rather than a destructive one and the people of Japan embraced it with eagerness. In the atmosphere of reform that characterized the occupation, an efflorescence of what Dower calls “cultures of defeat” emerged. For example, kasutori culture explored the sleazy underside of urban life. Radical political movements tested the limits—and sincerity—of American reformism. Changes in artistic images, popular entertainment, songs, jokes, and even the Japanese language itself reflect the vitality and diversity of Japanese culture during the American occupation.”

Read the full review here.

Kellianne King writes:

“Contraceptive Diplomacy travels uncharted territory by investigating transpacific attempts to bolster state power through a combination of birth control and eugenics. Takeuchi-Demirci’s work reminds us that U.S. eugenics projects did not exist in isolation, but on the world stage during a century fraught with international conflict. In working together to promote population control, Japan and the United States actually competed to demonstrate their cultural and scientific superiority. Feminist-led initiatives became, as Takeuchi-Demirci calls it, “a tool for patriarchal control and world domination” (210). Born in an anti-imperialist and socialist climate during the first World War, birth control traveled in imperialistic ways to facilitate international diplomacy. Takeuchi-Demirci shows the different ways discourses can be manipulated to serve dominant desires, and how even those who initially resisted this co-option, such as Sanger, become complicit. While the argument that eugenics served state goals is not particularly new, Takeuchi-Demirci does shed light on previously ignored Japanese-American projects. Her work makes this scholarly oversight appear all the more glaring given Sanger’s extensive involvement with the Japanese government and women’s groups.”

Read the full review here.

Edgar Walters writes:

“Musui’s Story is an exceptional account of one man’s hell-raising, rule-breaking, and living beyond his means. The autobiography documents the life of Katsu Kokichi, a samurai in Japan’s late Tokugawa period who adopted the name Musui in his retirement. Katsu is something of a black sheep within his family, being largely uneducated and deemed unfit for the bureaucratic offices samurai of his standing were expected to hold. As such, he typifies in many ways the lower ronin, or masterless samurai, many of whom famously led roaming, directionless lives and wreaked havoc among the urban poor and merchant classes. The autobiography follows Katsu’s whirlwind of adventures, which involved a great deal of fighting, name-calling, and extortion. What Katsu lacks in ambition is more than made up for by his knack for getting into trouble. The supposed premise of the autobiography is to serve as a cautionary tale for his descendants, as Katsu advises from the very beginning, “Take me as a warning.” In actuality, however, the story smacks of a thinly veiled account of braggadocio.”

Read the full review here.