Notes from the Field is a series with a long history at NEP. In this latest iteration, the series has three broad areas of focus. First, Notes from the Field is designed to take readers into unexpected corners of the world’s great archives and to explore the experience of working there. We aim to describe some of the spaces and places in which historians work every day. Second, we’re interested in fascinating stories that might not become the central focus of a book or an article but which nonetheless reveal intriguing corners of the past. And third the series discusses the often unexpected experiences of doing fieldwork in which each day can bring new challenges, joys or discoveries. Together these stories form our new Notes from the Field. Below we collect some of the wonderful early iterations of this series, seven pieces that illuminate different archives and the experience of working as historians. Together these stories create a tapestry of historical practice.

Mary Neuburger writes about her research on Tolstoyan-inspired vegetarianism in Bulgaria:

“By 1907, Bulgarian Tolstoyans had broken ground on their own agricultural commune in Yasna Polyana…The ties to Tolstoy were so strong that many claim that he was headed to Bulgaria in his final days—when he famously left his family estate and headed south. Alas, he died along the way. But if anything, the Tolstoyan movement gained in strength after his death, especially in the aftermath of World War I. The massive human casualties of the war brought an even greater urgency to the Bulgarian (and global) Tolstoyan project… I was most interested in the vegetarian strand of the commune’s intellectual and organizational work… This story is best told in a global context, and meat was one of the most hotly debated food sources in history—in the past as today. Is eating meat a human instinct or a learned behavior? Is it the gold standard of fortification, or will it kill us? Even if it is good for the human body, what about the ethics of killing animals, the implications of modern methods, or the environmental impacts of meat-eating?”

Read the full piece here.

Mary Neuburger writes about recovering Bulgarian food history through travelers’ accounts:

“The veritable sea of travelers’ accounts are among the sources that inform my current book project, a cultural history of food and drink in the Eastern Balkans, with a focus on Bulgaria from the 1860s -1989. Bulgarian foodways were clearly imprinted by the Empires that ruled or influenced the region, from the Ancient Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, to the Soviet. Some of these travelers were Bulgarians, mapping their own homeland and defining their own nation as they went, with the culture of food and drink as important components. But many more were foreigners who consumed and assessed food and drink as sources of pleasure and anxiety. They mapped patterns of restraint and gluttony, as well as the connections of food with identity, healing, and magic. They often used practices of food and drink—production, preparation, and etiquette—as a way of forming or confirming their own opinions about locals as savage and barbaric or alternatively as vigorous and sensible. Such accounts include mouth-watering descriptions of home-cooked meals and local inn or restaurant fare from the days of treks on oxen-drawn carts.”

Read the full piece here.

Mark Sheaves writes about research, travel, and research-through-traveling in Seville, Spain:

“It was a boiling hot day and I decided to take a break from my work. Offering a lazy “ciao” to the security guard on the way out, I walked into the wall of heat that surrounded this beautiful Andalus city in the summer. Strolling around the magnificent cathedral that integrates Moorish and Catholic elements, scurrying between the shadows provided by palm trees, I headed up one of the gaudy shopping streets that act as tributaries from the city’s historic center. Undistracted by the pulsating music and new flowery patterned shirts on display, my mind remained fixed on the sixteenth-century English merchant and botanist John Frampton, who had lived in the city nearly five centuries previously and was the subject of my research.”

Read the full piece here.

Andrew Straw writes about his reaction to the assassination of Russian politician Boris Nemtsov in 2015:

“When I came upon the news of Nemtsov’s murder two Friday nights ago, I immediately handed the iPad to my wife, and her jaw dropped. That Saturday morning, there was a pervasive shock — on Russian social media and in the state-run and independent media — because everyone knew Nemtsov. His political career in the 1990s included a post as Deputy Prime Minister in 1998 under Boris Yeltsin, and, before that, as Governor of the Nizhny Novgorod where he led agricultural and economic reforms. However, his liberalism often clashed with the former communist party members who made up much of the Russian government. More importantly, as corruption blossomed in the new Russian economy, he relentlessly attacked the perpetrators. His political career imploded because his idealism and activism had no place in the status quo Vladimir Putin created between society, the oligarchs and the state after 2000.”

Read to full piece here.

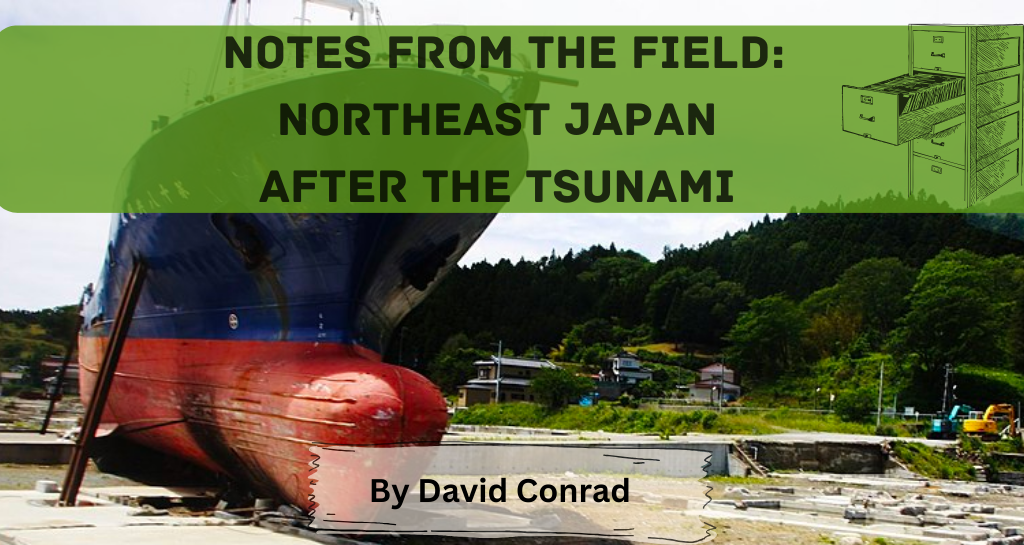

David Conrad writes about visiting the port city of Kesennuma, in northeastern Japan after it was hit by a deadly tsunami:

“Nothing I had heard could have prepared me for what I saw there. While many buildings I recognized were still standing, and some had already been rebuilt, large swaths of the town were simply gone. One of Kesennuma’s two rail stations had been destroyed, and I did not have a car, so I traveled there by bus. It dropped off in the middle of several cracked foundations. Only by memory could I tell that I was a stone’s throw from the site of a restaurant I used to frequent. A friend picked me up at the bus stop, and on our way to his home in my old neighborhood we passed a fishing vessel tipped on its side. The ocean was several meters away on the righthand side of the road, and the ship was on the left.”

Read the full piece here.

Joan Neuberger writes about a dinner at Trinity College, University of Cambridge, that shaped her research on Russian filmmaking:

“And yes, the Trinity dining hall looks just like the one at Hogwarts, with long tables and benches for students running the length of the hall and a more formal High Table along the width. It does, however, have only an ordinary, though impossibly high, ceiling made of wooden beams rather than one that reflects the weather, and while there are plenty of candles, they don’t float in the air. And then there’s Henry VIII. A large copy of Hans Holbein’s famous portrait of Henry, who founded Trinity, watches over diners, as imperious as ever, from above High Table at the end of the hall. What’s the connection between the accidents of research, a Soviet film about a bloody tyrant of the past –- a film that was commissioned by Joseph Stalin, bloody tyrant of the then-present — and Trinity High Table?”

Read the full piece here.

Kristie Flannery writes about how her archival research in Manila was interrupted by Pope Francis’ visit to the Philippines:

“It is not surprising that the government of the third largest Catholic country in the world would declare the days of the Pope’s visit “Special non-working days” in the national capital. All non-essential government activities (including the national archives) are closed, all school and university classes have been canceled, and many businesses will not open their doors. The enforced holiday is supposed to clear usually congested roads of cars and jeepneys so the Pope and pilgrims move more easily from A to B.”

Read the full piece here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.