When people outside of Mexico think of Día de Muertos, they often imagine something very specific: altars with multiple levels, covered in bright orange cempasúchil flowers, decorated sugar skulls, candles, and photos of the departed. It’s a beautiful image—one made globally familiar by films like Disney–Pixar’s Coco and even the opening sequence of the James Bond movie Spectre. These images have turned Día de Muertos into a global symbol of “Mexicanness,” blending heartfelt remembrance with cinematic spectacle. But they also tell only part of the story. Mexico is a vast and diverse country, and its ways of honoring the dead vary dramatically from one region to another.

There’s a common saying that “in the north, culture ends and the carne asada begins.” It’s usually meant as a joke, but it reflects how many people conceive of northern Mexico as less culturally developed when compared to the Indigenous and colonial legacies of the center and south. But that couldn’t be further from the truth. The north, and particularly the Yaqui and Mayo territories in Sonora and Sinaloa, hold some of the most fascinating and enduring traditions, especially concerning the remembering of the dead.

The Yaqui (or Yoeme) and Mayo (or Yoreme) peoples are two of the largest Indigenous groups in northwestern Mexico, living mainly along the Río Yaqui and Río Mayo valleys. Though distinct, they share close linguistic and cultural ties. For centuries, both groups have endured waves of encroachment—from colonial missions to persecution and extermination campaigns, and modern struggles over land and water rights.

Among the Yaqui and Mayo peoples, Día de Muertos has deep roots that blend Catholicism with Indigenous spiritual elements. The Jesuits, who arrived in the seventeenth century, left a long-lasting missionary legacy in the region. They introduced the Catholic calendar of saints, masses for the dead, and prayers for souls in purgatory—but these ideas intertwined with preexisting Indigenous understandings of the spirit world. The result is a complex, layered ritual cycle that lasts several weeks, involving tapancos (wooden altars built high above the ground), offerings of food, candles, and water, and collective gatherings and prayers in homes and cemeteries.

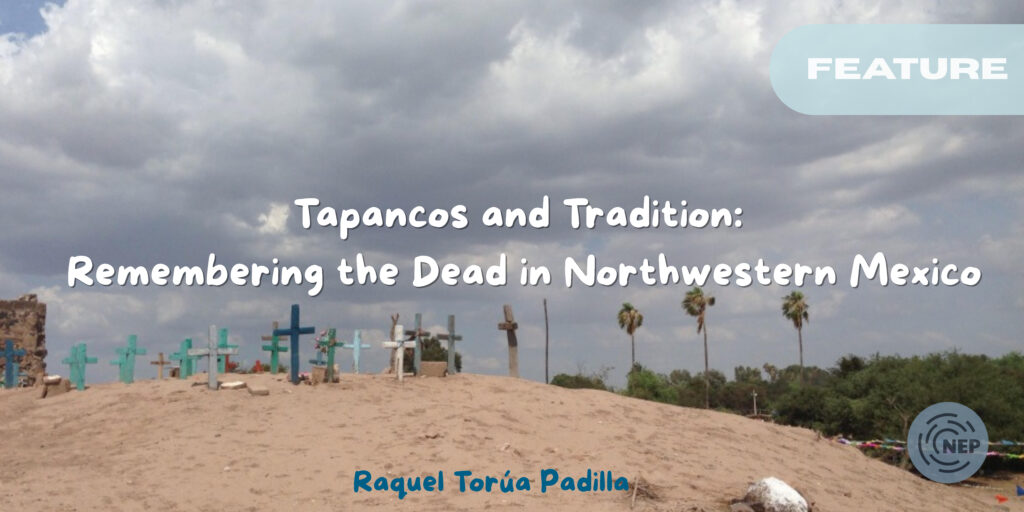

Yaqui cemetery. Source: author

When a Yaqui or Mayo person dies, a long spiritual process begins. Family members choose padrinos––often translated as “godparents,” though the term refers more broadly to ritual kin who sponsor key life events–– to help organize the funeral and the novenario—nine days of prayer that follow the burial. A year later, they hold the luto pajko, a ceremony marking the soul’s final passage into the Sewa Ania, or “Flower World.” During the year between death and the luto pajko, the spirit is believed to remain close to the living, not yet fully at rest. If Día de Muertos arrives before the luto pajko has taken place, the recently deceased are not yet included in the offerings, as inviting them too soon could prevent their soul from completing its journey.

For the Yaqui, the ritual cycle of the dead begins on October 1, when it is believed that souls begin their return to the world of the living. Members of the cofradía—local religious leaders who guide ceremonies in the absence of priests—build an altar draped in black cloth with a human skull placed on top. They then carry it from house to house, praying in what is called “the procession of the priest’s head”. This solemn procession happens every Monday throughout the month until the cycle concludes on November 30th.

Among the Mayo, the cycle begins a bit later, on October 24, when families start building their tapancos. A tapanco is simpler than the elaborate altars most may imagine—it’s placed outside on the patio and built high above the ground, about 1.5 to 2 meters tall. Four posts of mesquite wood support a mat or plank where offerings are placed. The four posts symbolize the padrinos who once carried the coffin, while the height of the altar reflects the belief that souls descend from above to receive their offerings.

This elevated structure echoes pre-Hispanic funerary practices, when both the Yaqui and Mayo bid farewell to their dead on raised platforms before eventual cremation. When the Jesuit missionaries arrived, they prohibited cremation, but Indigenous communities found a compromise: they kept the vertical structure and the symbolic presence of fire, now represented by candles burning beneath the tapanco. Food, water, and flowers are placed on top. However, unlike the popular imagery seen in films like Coco, photographs of the deceased are rarely used— mainly because photos have historically been difficult to obtain.

Tapanco Yaqui in Torim. Source: author

On November 2, Día de Muertos, the cofradía makes its rounds from home to home, praying and reciting aloud the names written in each libro de las ánimas, a sacred family book kept by Yaqui and Mayo households, that records the names of deceased relatives. When the prayers conclude, they receive the offerings as a token of gratitude for their work throughout the month. The tapanco remains standing for several weeks afterward, until November 30, when it is believed that the souls return once more to the Sewa Ania.

These are the only Indigenous groups in northwestern Mexico with such deep traditions surrounding Día de Muertos. This distinctiveness can be explained, in part, by the Jesuit presence in the Yaqui and Mayo valleys, where evangelization took root more firmly than among other Indigenous communities of the north. Even for mestizo families in northwestern Mexico, for much of the twentieth century, it was rare to celebrate Día de Muertos in this way. My parents, for example, grew up more with Halloween than with altars. Living close to the U.S.–Mexico border meant that American culture seeped in easily—pumpkins, trick-or-treating, and dressing up often replaced alebrijes and cempasúchil. Most families would go to mass or visit the cemetery, but altars were rare.

This started to change around the turn of the century, when the Mexican Education System began promoting school projects in which children built altars modeled after those from central Mexico. Suddenly, Día de Muertos aesthetics appeared in classrooms, civic plazas, and even shopping malls. It was part of a broader national effort to “standardize” cultural practices and promote a shared sense of Mexicanness.

These new practices didn’t erase local customs in indigenous territory, but they did reshape how younger generations of mestizos in the north think about Día de Muertos. My generation grew up making altars at school, learning the symbolism of each level, and memorizing the meaning of every element—from salt and water to papel picado. In a sense, we learned a nationalized version of the celebration, one that connects us to a broader Mexican identity but sometimes distances us from our own regional histories.

“Ofrenda del Norte” (Northern Offering). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The projects of the Mexican education system did not affect the Yaqui and Mayo, largely because these communities tend to be reserved and resistant to outside cultural interventions, and because the policies were primarily aimed at mestizo populations to counter U.S. cultural influences rather than reshape Indigenous traditions. However, there has been little reflection or critique from the northern mestizo population itself, despite their pride in regional identity.

In places like the Yaqui and Mayo towns along the Río Yaqui and Río Mayo valleys, older traditions persist. There, the ceremonies remain community-centered, intimate, and deeply spiritual. The tapancos are still built. The souls of the dead are still awaited and welcomed home. And these practices remind us that the north has always been a region of cultural richness, adaptation, and resilience.

So perhaps there is culturally more to Northern Mexico than carne asada. The north is not a cultural void—it’s a crossroads. It’s where Indigenous, missionary, and transborder influences coexist, sometimes uneasily, sometimes harmoniously. Día de Muertos in the north may not always look like the ones in Oaxaca or Michoacán, but it carries the same essence: remembering, honoring, and reaffirming the ties that bind the living and the dead.

Raquel Torua Padilla is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a B.A. in History from the Universidad de Sonora and is currently a CONTEX Fellow. Her research focuses on the history of the Yaqui people in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.