As we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, it’s easy to imagine the 1860s as a historical stage dominated by northerners and southerners, fighting to make their voices heard as the debates about slavery and the great drama of emancipation unfolded in a series of costly battles and sweeping presidential proclamations. While that narrative certainly serves as a key to our nation’s history, Scott Berg urges us to broaden our geographic perspective to include the Western US to fully understand a decade that saw the nation splinter, reunify, and begin to grapple with new definitions of “freedom.” In his new book, 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End, Berg casts this decade as a pivotal moment of contention when the Dakota nation staked a claim to their land in a series of battles that would come to be known as the Dakota War of 1862.

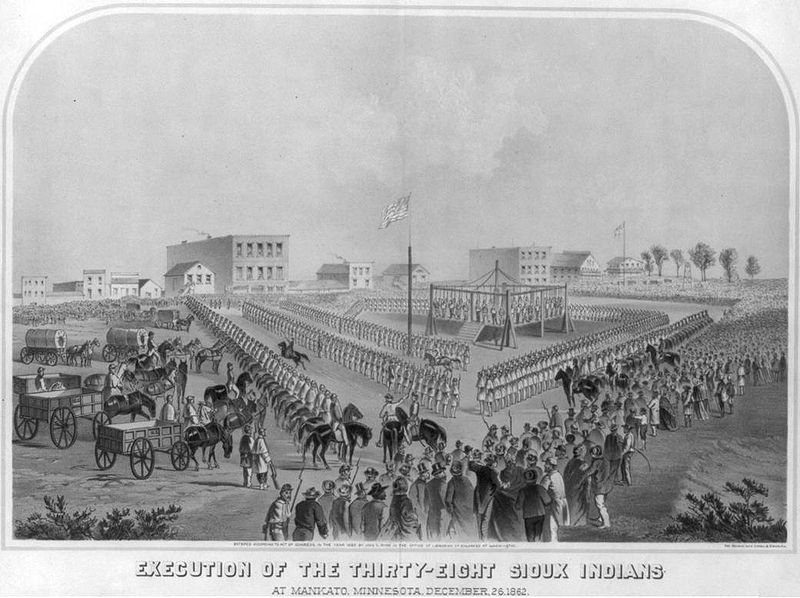

In twenty brief yet power-packed chapters, Berg uses a variety of sources to tell the social, political, and military story of the Dakota people leading up to and during the war, drawing heavily on the narrative of a captive white woman named Sarah Wakefield who lived with the Dakota nation for most of the duration of the conflict. As Civil War raged in the east, Berg recounts how the Dakota left towns smoldering in their wake, capturing women and children, only to face extreme retaliation from whites who failed to see how continued encroachment on Native lands and delayed annuity payments might have lead to their current predicament. By December 26, 1862, approximately four months after the start of open hostilities, violence between the Dakota and their white counterparts had escalated to such a fever pitch that President Lincoln himself would order thirty-eight Dakota men – after questionable trials and some faulty convictions – hanged for their actions. With a stroke of his pen, Lincoln effectively ordered the largest federally sanctioned mass execution in the nation’s history. When one compares the result of this conflict with the results of the Civil War, this decision suggests that punishment for violent action against the federal government had a decidedly racial dimension. Over one million southern whites took up arms against the Union to defend slavery in a conflict that saw massacres on an unprecedented scale for four years, and yet the former Confederacy faced only one execution as punishment for its rebellion. In the West, on the other hand, when a few hundred Dakota took violent action to ensure that the government upheld its end of the treaty and protected Dakota lands in a set of conflicts that lasted less than a year, the result was the largest government approved mass execution in our nation’s history. In the context of the 1860s, the federal government, Lincoln included, meted out “justice” in racial terms as those who challenged the government in the East faced a much different fate than those who defied the government in the West.

In twenty brief yet power-packed chapters, Berg uses a variety of sources to tell the social, political, and military story of the Dakota people leading up to and during the war, drawing heavily on the narrative of a captive white woman named Sarah Wakefield who lived with the Dakota nation for most of the duration of the conflict. As Civil War raged in the east, Berg recounts how the Dakota left towns smoldering in their wake, capturing women and children, only to face extreme retaliation from whites who failed to see how continued encroachment on Native lands and delayed annuity payments might have lead to their current predicament. By December 26, 1862, approximately four months after the start of open hostilities, violence between the Dakota and their white counterparts had escalated to such a fever pitch that President Lincoln himself would order thirty-eight Dakota men – after questionable trials and some faulty convictions – hanged for their actions. With a stroke of his pen, Lincoln effectively ordered the largest federally sanctioned mass execution in the nation’s history. When one compares the result of this conflict with the results of the Civil War, this decision suggests that punishment for violent action against the federal government had a decidedly racial dimension. Over one million southern whites took up arms against the Union to defend slavery in a conflict that saw massacres on an unprecedented scale for four years, and yet the former Confederacy faced only one execution as punishment for its rebellion. In the West, on the other hand, when a few hundred Dakota took violent action to ensure that the government upheld its end of the treaty and protected Dakota lands in a set of conflicts that lasted less than a year, the result was the largest government approved mass execution in our nation’s history. In the context of the 1860s, the federal government, Lincoln included, meted out “justice” in racial terms as those who challenged the government in the East faced a much different fate than those who defied the government in the West.

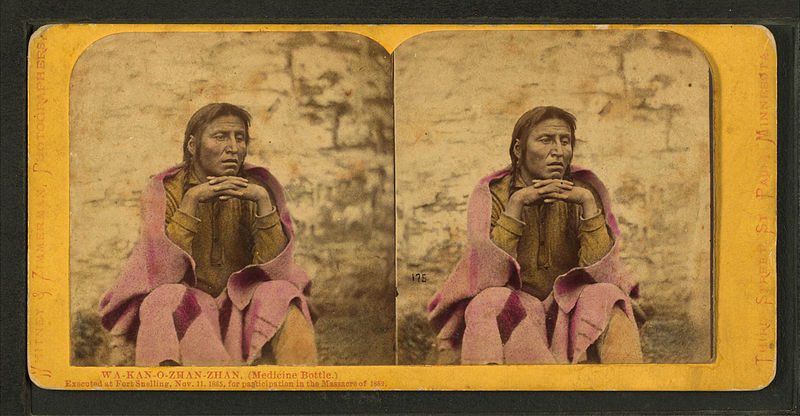

More than just a story of battles and raids, however, Berg manages to give both an on-the-ground, local perspective of the violence in Minnesota and widen his lens to put the conflict in a national context.. Lincoln, George McClellan, and John Pope all find space in Berg’s pages as he draws interesting connections between the Indians wars in the West and the Civil War in the East. In one particularly striking example, Berg describes a group of recently captured Dakotas held at Fort Snelling as the government continued to pursue Little Crow and his band. Six-hundred captives stood on the banks of the Mississippi River and watched the approach of a steamboat – the Northerner – that would transport them out of Minnesota to a reservation in southern Dakota territory. They quickly noticed that the boat was peopled “by a hundred or so black men from the southern reaches of the Mississippi, contraband slaves who were now free under the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation,” brought north to be used in the effort to subdue the unyielding bands of Dakota warriors. In that moment, Berg tells us that “captive Indians and free blacks exchanged stares and, according to one observer, entered into conversations that were not recorded by any reporter, diarist, or letter writer.” If one was to speculate on the nature of that exchange (and Berg does not), it seems quite possible that both parties – neither unfamiliar with the other – would find more than a little irony in their new situations and their changed relationship to whites.

More than just a story of battles and raids, however, Berg manages to give both an on-the-ground, local perspective of the violence in Minnesota and widen his lens to put the conflict in a national context.. Lincoln, George McClellan, and John Pope all find space in Berg’s pages as he draws interesting connections between the Indians wars in the West and the Civil War in the East. In one particularly striking example, Berg describes a group of recently captured Dakotas held at Fort Snelling as the government continued to pursue Little Crow and his band. Six-hundred captives stood on the banks of the Mississippi River and watched the approach of a steamboat – the Northerner – that would transport them out of Minnesota to a reservation in southern Dakota territory. They quickly noticed that the boat was peopled “by a hundred or so black men from the southern reaches of the Mississippi, contraband slaves who were now free under the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation,” brought north to be used in the effort to subdue the unyielding bands of Dakota warriors. In that moment, Berg tells us that “captive Indians and free blacks exchanged stares and, according to one observer, entered into conversations that were not recorded by any reporter, diarist, or letter writer.” If one was to speculate on the nature of that exchange (and Berg does not), it seems quite possible that both parties – neither unfamiliar with the other – would find more than a little irony in their new situations and their changed relationship to whites.

A professor of nonfiction writing, Berg’s command of the literature and engaging writing style combine to give him that elusive blend of readable narrative and accessible analysis. Instead of casting our eyes back and forth between the North and South, with occasional glances over our shoulders to the West to see if slavery would flourish there, Berg shows us how Native actions on the Minnesota frontier made their way back to Washington and landed on the desk of a President who, though mired in a Civil War, was forced to listen to Native voices of dissent and grapple with instances Native resistance in a conflict that would set the stage for the Battle of Little Bighorn and Wounded Knee.

A professor of nonfiction writing, Berg’s command of the literature and engaging writing style combine to give him that elusive blend of readable narrative and accessible analysis. Instead of casting our eyes back and forth between the North and South, with occasional glances over our shoulders to the West to see if slavery would flourish there, Berg shows us how Native actions on the Minnesota frontier made their way back to Washington and landed on the desk of a President who, though mired in a Civil War, was forced to listen to Native voices of dissent and grapple with instances Native resistance in a conflict that would set the stage for the Battle of Little Bighorn and Wounded Knee.

Photo Credits:

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper depicting the execution of 38 Sioux in Mankato, Minnesota, January 24, 1863 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Stereoscopic image of Wa-kan-o-zhan-zhan (“Medicine Bottle”), a Native American executed in 1865 for his participation in the 1862 Dakota War (Image courtesy of New York Public Library)