Johnny Tremain Cover (via Wikipedia)

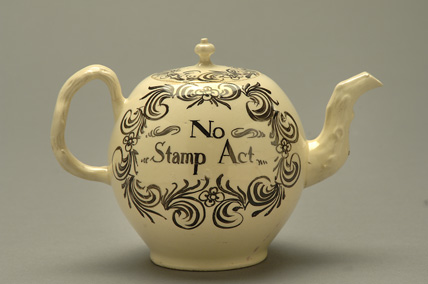

As a historian of early America, my subject predates the invention of film or video, voice or music recording, or even photography. When I watch my modernist colleagues deliver multi-media lectures – including film clips, snatches of popular music or speeches, and photos – I feel a twinge of envy. The closest 18th-century Americans ever got to a multi-media presentation was to paint the words: “No Stamp Act!” on the side of a porcelain teapot. A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the Boston tea party, including reading contemporary newspaper accounts, letters, and cartoons, I treated my students (and I will admit, myself) to the Boston tea party scene from Disney’s 1957 film Johnny Tremain, based on the 1943 novel by Esther Forbes. The depiction of the “tea party” as an oddly orderly act of vandalism is probably accurate, but one cannot escape the impression of watching 1950s Americans playing at being 18th-century revolutionaries, and not even bothering to wash the Brylcreem out of their hair. Of course, as I told my students (in self-defense) before showing them the clip, any historical film is a document of the age that produced it rather than of the age it depicts. So what can Johnny Tremain tell us about America in the 1950s?

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the Boston tea party, including reading contemporary newspaper accounts, letters, and cartoons, I treated my students (and I will admit, myself) to the Boston tea party scene from Disney’s 1957 film Johnny Tremain, based on the 1943 novel by Esther Forbes. The depiction of the “tea party” as an oddly orderly act of vandalism is probably accurate, but one cannot escape the impression of watching 1950s Americans playing at being 18th-century revolutionaries, and not even bothering to wash the Brylcreem out of their hair. Of course, as I told my students (in self-defense) before showing them the clip, any historical film is a document of the age that produced it rather than of the age it depicts. So what can Johnny Tremain tell us about America in the 1950s?

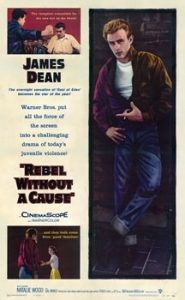

At the start of the film, Johnny Tremain, a young orphan and silversmith’s apprentice, is portrayed as petulant, conceited, and disdainful of authority. In one scene that anyone who has ever seen the movie will remember, Johnny breaks the rules by working on the Sabbath and gets his come-uppance when he accidentally puts his hand into a puddle of molten silver. Audiences in the 1950s would likely have recognized Johnny as a colonial version of an emerging cultural phenomenon: the “teenager.” Newspapers, radio, and the new medium of television were full of stories of teenage “rebellion,” which, sociologists warned, was creating a new social problem called “juvenile delinquency.” In the spring of 1954, a Congressional sub-committee held televised hearings on the causes of juvenile delinquency that competed for viewers’ attention with the simultaneous, and subsequently far more famous, Army-McCarthy hearings. The troubled and violent teen became a common character in popular films. Perhaps the best known were Marlon Brando in “The Wild One” (1953), and James Dean in “Rebel without a Cause” (1955).

Theatrical Release Poster, 1955 (via Wikipedia)

Hal Stalmaster, who plays Johnny Tremain, is no Brando or Dean in terms of acting skills. Similarly, Johnny’s angst is depicted far more crudely; with a crippled hand he literally cannot find a place for himself in society.

Fortunately, the American Revolution arrives to give Johnny a healthy outlet for his destructive (and patricidal) impulses. At the tea party, Johnny gleefully smashes tea chests alongside approving and participating adults (Paul Revere, Sam Adams, and Joseph Warren). Even an on-looking British admiral admires the tea partiers’ politeness and principles. The only disapproving authority figure is, significantly, also Johnny’s only blood relation, his uncle, played with panache by Sebastian Cabot as an effete popinjay who is eventually revealed to be an anti-revolutionary loyalist and thus, in a phrase that was loaded with meaning in the 1950s, “un-American.” The film’s depiction of the American Revolution as an Oedipal conflict resembles (in a far less disturbing and simplified fashion) the version provided by Nathaniel Hawthorne in his 1831 short story: “My Kinsman, Major Molineaux.”

After the tea party, Johnny joins the “Sons of Liberty” and becomes active in the revolutionary underground. Eventually, he finds himself on Lexington green when the first shots in the war are fired, and takes part in the running battle to drive the redcoats back to Boston. The film ends that night with Johnny in the camp of the patriot army gathering outside of Boston, a warrior in the cause of American (and his own) freedom. But unlike Forbes’s novel, in which the outbreak of the war (and the death of a friend) forces Johnny to grow up and accept the responsibilities of adulthood, the film’s Johnny makes no such psychological breakthrough. He is the same callow, smart-alecky teen at the film’s end as at the beginning. War (and revolution) do not change him. In the film’s depiction of combat, it is disconcerting to watch Johnny cackle with laughter as he ambushes and kills the king’s soldiers (as if fulfilling a long repressed desire). The film also shies away from espousing any overt political ideology. James Otis, the only character in the film who tries to articulate a larger meaning to the struggle, is described and portrayed as mentally unbalanced.

The film’s reluctance to ground the revolution on either abstract ideals or nitty-gritty class struggle closely reflects the views of American historians writing in the 1950s, who argued that, by crossing the ocean, the colonists had left the ideological conflicts of the old world behind them and instead shared in a broad liberal consensus. In 1955, Louis Hartz argued, in The Liberal Tradition in America, that colonial American society was an egalitarian world of small property holders. Lacking either an aristocracy or a peasantry, concepts such as class (and class struggle) were meaningless. Not that they thought about politics much. Lockean, possessive individualists by nature rather than persuasion, early Americans were blessed with a “charming innocence of mind.” For obvious reasons, these historians tended to focus their attention on the northern colonies, where slavery was of relatively small consequence.

In retrospect, one can readily see how the hopes and fears of larger 1950s society shaped this so-called “consensus school” of early American history, both in terms of its celebration of middle class values and bourgeois conformity, and its dread of radicalism. Forbes’s novel, written in 1943, reflected the concerns of the depression era and was far more focused on issues of class and poverty than was the film. After a brief theater run – it premiered on July 4, of course – Johnny Tremain was broadcast on Disney’s weekly television program in 1958 and was rerun many times thereafter. Like me, the vast majority of Americans probably first saw Johnny burn his hand in the comfort of their living rooms. For this reason, Johnny Tremain perhaps should be compared not to contemporary movies, but to 1950s television. More than Brando or Dean, the fictional teen who Stalmaster’s Johnny Tremain most closely resembles is Eddie Haskell, played by Ken Osmond in the T.V. series Leave it to Beaver, who made his first appearance in 1957. Although a wiseass and troublemaker when adults are absent, Eddie’s sycophancy in their presence indicated his desire to conform. Likewise, with the singular exception of his loyalist uncle, Johnny is deferential to all the adults in the film. Even when he takes up arms against the establishment, it is a reflexive, almost thoughtless, act rather than the result of a deliberate decision to turn the world upside down or from a radical hope to build a new heaven and a new earth. Johnny Tremain’s version of the revolution is an orderly one, in which rebellious teens fall in line behind their patriotic elders, Brylcreem tubes in hand.

For more on history writing in the 1950s, see

Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession

On the invention of juvenile delinquency:

James Gilbert, A Cycle of Outrage: America’s Reaction to the Juvenile Delinquent in the 1950s

On the Boston Tea Party, take a look at:

Alfred Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution