One of the core values of studying history is objectivity: an ability to weigh evidence, read documents and then dispassionately judge the actions of our ancestors. But let’s be honest, it’s impossible to study the past without feeling something. Confusion, fascination, excitement—this is what motivates historians to spend their days poring over obscure manuscripts.

Is it possible that emotions actually help to produce better history? Sweden’s Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of medical arts thinks so. So when readers navigate its stunning online archive of medical, zoological and biological documents from the 15th-20th-century world, “Emotion” is literally a search option. In addition to place and topic, users can select a set of documents based on the feelings they evoke.

Is it possible that emotions actually help to produce better history? Sweden’s Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of medical arts thinks so. So when readers navigate its stunning online archive of medical, zoological and biological documents from the 15th-20th-century world, “Emotion” is literally a search option. In addition to place and topic, users can select a set of documents based on the feelings they evoke.

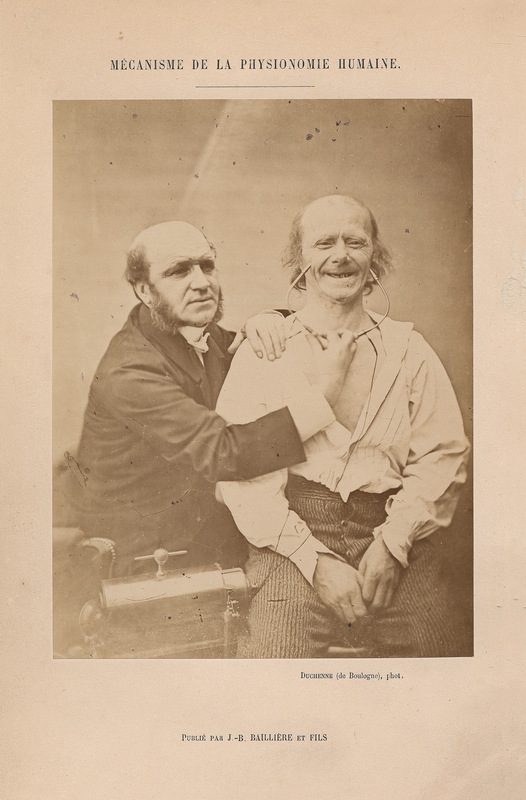

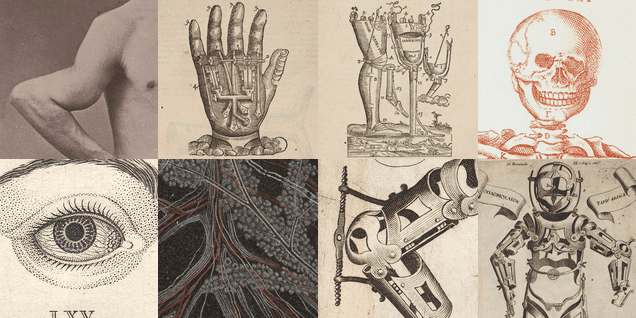

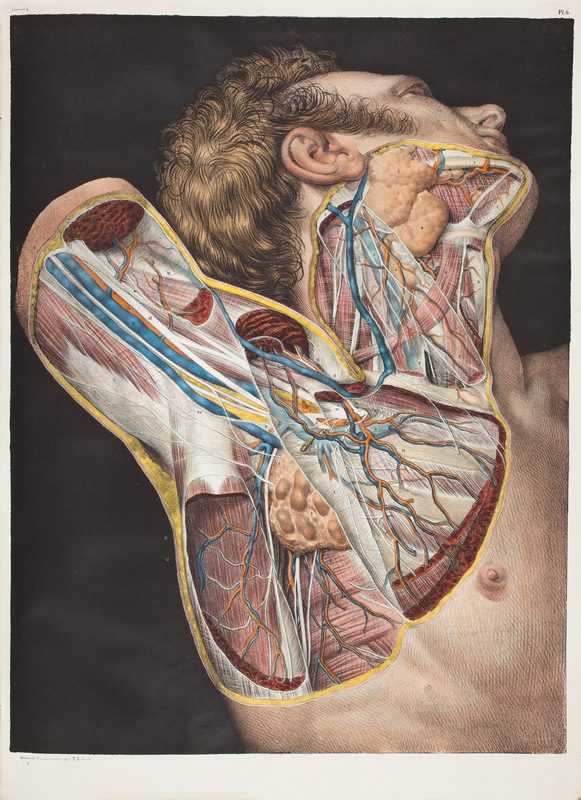

And each category seems very appropriately titled. “Beautiful” cues a stunning collage of images from across time and space: a 17th-century Dutch anatomical display of the human skeleton, an early modern Italian etching of mythical beasts, and one Viennese botanist’s exquisite rendering of a strawberry. True to form, “Scary” turns toward the macabre, with gruesome surgical photographs of American Civil War amputees, a 16th-century doctor’s guide to battle wounds and a European naturalist’s perturbing bat exhibit. “Fascinating” lies somewhere in between. There are photographs of French psychiatry patients gawking at the camera as they’re examined, sublime—yet slightly unsettling—medical lithographs of the human form, and even a 19th-century physician’s guide to the miracle of life. Depending on your mood, you can also peruse the Artistic, the Colorful, the Instructive, the Marvelous, the Remarkable and the Strange.

And each category seems very appropriately titled. “Beautiful” cues a stunning collage of images from across time and space: a 17th-century Dutch anatomical display of the human skeleton, an early modern Italian etching of mythical beasts, and one Viennese botanist’s exquisite rendering of a strawberry. True to form, “Scary” turns toward the macabre, with gruesome surgical photographs of American Civil War amputees, a 16th-century doctor’s guide to battle wounds and a European naturalist’s perturbing bat exhibit. “Fascinating” lies somewhere in between. There are photographs of French psychiatry patients gawking at the camera as they’re examined, sublime—yet slightly unsettling—medical lithographs of the human form, and even a 19th-century physician’s guide to the miracle of life. Depending on your mood, you can also peruse the Artistic, the Colorful, the Instructive, the Marvelous, the Remarkable and the Strange.

The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library of medical arts is a strange, colorful and captivating resource for scholars and the general public, especially those interested in the history of science, medicine and its visual portrayals. But its unorthodox design openly challenges the assumption that historians ought to leave their emotions at the archive door. Instead, it asks users to take a risk—to forgo the comforts of traditional categories and experiment. And perhaps most importantly, the site acknowledges that our own emotional reactions are of historical significance. By declaring 17th-century medical drawings to be “strange,” we reveal our own modern biases—arrogance, even—about the past. This is a subversive new form of research in which emotions do not distort historical understanding, but actually enable more of it.

Don’t miss the latest New Archive posts:

How does the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary relate to the present crisis in the Ukraine?

And what does the local music in Carlistrane, Ireland sound like?

Photo Credits:

Screenshot of Wunderkammer’s “Fascinating” gallery (Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library)

Anatomical plate from Traité complet de l’Anatomie de l’Homme, 1867–1871. Found in Wunderkammer’s “Fascinating” section (Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library)

Portrait of a psychiatric patient from Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, 1876. Found in Wunderkammer’s “Fascinating” section (Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library)