I recently came across John Winthrop’s sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity,” delivered in 1630 on a boat to those about to establish a “New England” across the ocean from the old. Winthrop urged his congregation to create a “city upon the hill,” a model for others to imitate. Ever since Winthrop, the meaning of that city has been hotly debated. It is clear, however, that Winthrop’s city has come to stand for the ongoing experiment that is America: unique, exceptional, inspiring. Modern rebels, like those who have gathered on a platform of social and cultural conservatism around the Tea Party, a name full of references to Puritan Massachusetts, owe Winthrop, their alleged ideological ancestor, a careful reading.

Winthrop was a man of his age. He understood societies to be naturally divided into two camps: the “great ones” and the “inferior sort.” He thought that, for all their divisions, societies had built-in limits to social polarization so “that the riche and mighty should not eat up neither the poor, nor the poor and despised rise up against and shake off their yoke.” Natural instincts pushed the rich to be merciful and the poor not to be too rebellious. A society that has lowered the taxes of the wealthy so that it could then dismantle both collective bargaining and public education would have puzzled Winthrop. He would have been surprised by last summer’s developments in Wisconsin.

Winthrop was a realist and acknowledged that there were limits to giving and forgiving. Individuals needed to put aside some of their wealth to guard against future hardship; they needed to take care of their family before they practiced charity. According to Winthrop, even the Bible found this prudence virtuous: the wise Egyptian Joseph put grain away and saved his treasonous brethren, the sons of Jacob, from famine when drought struck Israel. Winthrop, however, also thought that members of communities under siege demonstrated unusual degrees of solidarity. Natural law dictated that, under these circumstances, the wealthy would openly share their property. Winthrop would have not recognized his city upon the hill in America today: a society whose most needy voluntarily sign up to fight wars while the most powerful avoid such sacrifices and tirelessly lobby to get ever larger tax cuts.

Winthrop was a realist and acknowledged that there were limits to giving and forgiving. Individuals needed to put aside some of their wealth to guard against future hardship; they needed to take care of their family before they practiced charity. According to Winthrop, even the Bible found this prudence virtuous: the wise Egyptian Joseph put grain away and saved his treasonous brethren, the sons of Jacob, from famine when drought struck Israel. Winthrop, however, also thought that members of communities under siege demonstrated unusual degrees of solidarity. Natural law dictated that, under these circumstances, the wealthy would openly share their property. Winthrop would have not recognized his city upon the hill in America today: a society whose most needy voluntarily sign up to fight wars while the most powerful avoid such sacrifices and tirelessly lobby to get ever larger tax cuts.

But it is perhaps the failure of America to live up to the laws of a Christian community that would have disoriented Winthrop. Winthrop made a distinction between societies ruled solely by natural law and those ruled by the “law of Grace or of the Gospel.” Christian societies were bodies whose disparate parts were also glued by the ligaments of “love.” For all our desire to remember the Pilgrims as peaceful Christians who fled England to escape persecution, the fact is that Puritans were just as intolerant as their enemies, and Winthrop was no exception. Winthrop drew a clear line separating true Christians from the rest. He argued that the ligament of love worked best in communities that were ideologically homogenous. And yet, Winthrop did think that love caused communities to be more egalitarian. His model was the primitive Church whose members “had all things in common, neither did any man say that which he possessed was his own.”

Tea Party radicals, the alleged ideological heirs of men like Winthrop, might be surprised by Winthrop’s views on love and same-sex relationships. Winthrop’s descriptions of the love required to create his city on the hill are moving. His examples are all biblical. He explained that the love Eve felt for Adam was so carnal because her flesh literally came from Adam’s. But Winthrop also acknowledged the love Jonathan felt for David, the courageous shepherd who would soon dethrone Jonathan’s father, Saul. Winthrop was deeply aware of the force and depth of homoerotic love: “so that it is said [Jonathan] loved [David] as his own soul.” These two lovers would have their hearts broken when they were apart, “had not their affections found vent by abundance of tears.” Winthrop also considered the love of Ruth and Noemi exemplary.

Tea Party radicals, the alleged ideological heirs of men like Winthrop, might be surprised by Winthrop’s views on love and same-sex relationships. Winthrop’s descriptions of the love required to create his city on the hill are moving. His examples are all biblical. He explained that the love Eve felt for Adam was so carnal because her flesh literally came from Adam’s. But Winthrop also acknowledged the love Jonathan felt for David, the courageous shepherd who would soon dethrone Jonathan’s father, Saul. Winthrop was deeply aware of the force and depth of homoerotic love: “so that it is said [Jonathan] loved [David] as his own soul.” These two lovers would have their hearts broken when they were apart, “had not their affections found vent by abundance of tears.” Winthrop also considered the love of Ruth and Noemi exemplary.

The city upon the hill that Winthrop sought to create in New England is a different world from that of his alleged ideological heirs. For Winthrop, the stakes of getting the city right were high (and they continue to be). To build a lasting “city upon the hill” the Puritans needed to create a society held together by charity, mercy, and love. A danger loomed: this new experiment could be overtaken by lack of either foresight or solidarity. Puritans then would meet the fate of so many failed social experiments. So let’s take Winthrop’s parting words as a warning: “The eyes of all people are upon us. So if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

The text of the sermon can be found here.

President John F Kennedy on the City Upon a Hill: video/audio

President Ronald Reagan on the City Upon a Hill, text

To read more of Canizares-Esguerra on Puritans in North American see our monthly feature on his work from May 2011.

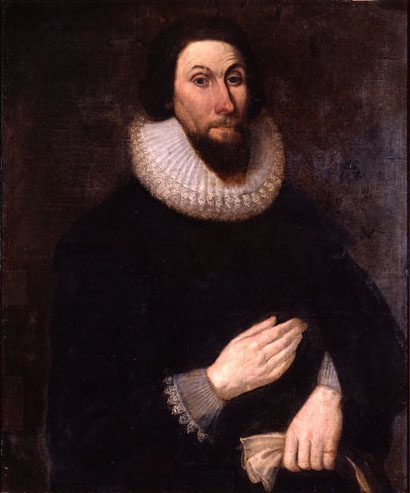

Portrait of John Winthrop, author unknown.

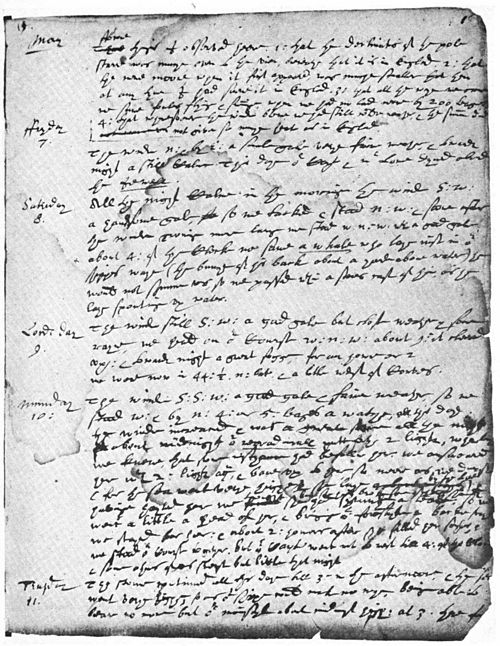

Page from John Winthrop’s journal: Wikisource, The Founding of New England