“Historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory,” wrote Robert Penn Warren in a preface to a poem on Thomas Jefferson in 1953. “For if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.”

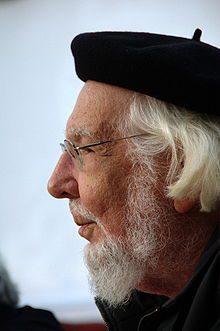

Warren’s poem, Brothers to Dragons, was an objection to Jefferson’s complicity in the slave trade as well as an appeal for the conciliation of poetry and history. Nicaraguan priest, poet, and revolutionary Ernesto Cardenal has enlisted in this select brigade of historian-poets with a remarkable work of art and history. The Doubtful Strait is entirely composed of dozens of historical documents rearranged, but not rewritten, to form an epic poem made up of 25 cantos. Originally published in Spanish in 1966, Cardenal uses the chronicles of Nicaragua’s discovery, conquest and sordid colonial misrule in the sixteenth century to condemn its present under the Somoza regime.

Warren’s poem, Brothers to Dragons, was an objection to Jefferson’s complicity in the slave trade as well as an appeal for the conciliation of poetry and history. Nicaraguan priest, poet, and revolutionary Ernesto Cardenal has enlisted in this select brigade of historian-poets with a remarkable work of art and history. The Doubtful Strait is entirely composed of dozens of historical documents rearranged, but not rewritten, to form an epic poem made up of 25 cantos. Originally published in Spanish in 1966, Cardenal uses the chronicles of Nicaragua’s discovery, conquest and sordid colonial misrule in the sixteenth century to condemn its present under the Somoza regime.

If Warren’s Brothers to Dragons is a condemnation of a revered but long-dead American head of state, Cardenal’s poem is an indictment of a considerably bolder nature, targeting the infamous contemporary Somoza dynasty that ruled Nicaragua from 1937 until the 1979 Sandinista revolution. The method employed by The Doubtful Strait is similarly bold. In the early 1960s, Cardenal combed the Nicaraguan archives, the Colección Somoza, retooling the archive’s documents into a poetic arsenal. From the Colección was born a collage comprised of otherwise unaltered historical documents arranged into a seamless body of poetry. The woes of 1960s Nicaragua are in this way masked in the historical documents of the 1500s and early 1600s, and dictators Luis (1922-1967) and Anastasio Somoza (1925-1980) are transfigured into reviled colonial governors Dávila (1440-1531) and de Contreras (1502-1558). The struggles of those trodden upon by the Spanish colonists and governors reflected in colonial petitions and chronicles implicitly mirror oppression in 1960s Nicaragua. The idioms of divine Judgment and liberation theology are brought to the fore with the masterful subtlety of a seasoned priest. A hypnotic rhythm of archaic legalese, often masking brutal acts of violence committed by Dávilas and de Contreras against Indians and colonists, regiments the poem’s flow. By enticing the reader to engage with rather restricted historical documents with the interpretive eye of the poet, The Doubtful Strait achieves a rare and lasting power as a condemnation of the Somoza monocracy.

Cardenal’s vulnerable position under the watchful eye of the Somoza dictatorship ultimately drives The Doubtful Strait to its most curious aspect – an outward absence of authorial fingerprints. Obscured behind historical documents from the Colección Somoza, the poet fades into his sources. Present only as an unseen Creator in a constellation of testimonies by oppressors, champions, and victims of Nicaragua’s past, Cardenal creates his diatribe without once authoring a line of prose. The result is a subversive work of poetry reminiscent of Ezra Pound and favorably likened to Pablo Neruda’s masterpiece, the Canto general, and yet created without a single stroke of the quill.

Written in prose constructed exclusively from centuries-old documents, The Doubtful Strait may appear of limited interest to the casual reader. But the questions its format raises are intriguing and have broad appeal: should such works be shelved under history, or poetry, or both? Are poetry and history altogether unlike? What responsibilities do poets and historians each come to shoulder in shaping our societies?

“The chronicler must not fail to do his duty.” Cardenal borrows verbatim these words aimed by historian Antonio de Herrera (1549-1626) in condemnation of brutal Governor Dávila. Surely enough, as insurgent Nicaraguans began to unravel the Somoza regime in 1977, Cardenal’s socialist community on the island of Solentiname would be bombarded and the poet sent into exile for subversive beliefs. After fighting for the Sandinista cause and serving as the Minister of Culture for the victorious insurrection, today Cardenal claims political persecution under a new “family dictatorship” – that of Sandinista strongman Daniel Ortega.

Following in the footsteps of Antonio de Herrera and Robert Penn Warren, this historian-poet uses memory to devastating effect. And like many historians and poets, Cardenal fulfills the chronicler’s duty – to remind us that, however different the façade, the past is often not even past.

You may also like:

Cristina Metz’s review of Greg Grandin’s The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War.