On November 11, 1938, Pearl Buck awoke to learn that she had won the Nobel Prize for Literature.Her first reaction—in Chinese—was “Wo bu xiangxin (我不相信)” or “I don’t believe it.” She added in English: “That’s ridiculous. It should have gone to [Theodore] Dreiser.” Despite tremendous popular support, the literary establishment shared Buck’s disbelief. Critic Norman Holmes Pearson labeled the choice “hammish,” while William Faulkner derided Pearl as “Mrs. Chinahand Buck.” To this day, scholars often dismiss Buck’s writings as didactic or trite.

Pearl Buck was the first American woman—and only the third American after Sinclair Lewis (1930) and Eugene O’Neill (1936)—to win the Nobel Prize. Many of her contemporary critics burned with obvious misogyny, a racist disinterest in her Chinese subjects, and just plain jealousy at her titanic commercial success. Indeed, although writers win the Nobel for their body of work, it was Buck’s smash-hit novel The Good Earth (1931) that had most seized the world’s attention.

Pearl Buck was the first American woman—and only the third American after Sinclair Lewis (1930) and Eugene O’Neill (1936)—to win the Nobel Prize. Many of her contemporary critics burned with obvious misogyny, a racist disinterest in her Chinese subjects, and just plain jealousy at her titanic commercial success. Indeed, although writers win the Nobel for their body of work, it was Buck’s smash-hit novel The Good Earth (1931) that had most seized the world’s attention.

Despite scholarly reserve, The Good Earth is a remarkable novel. Many critics have chosen to see simplistic melodrama and even offensive stereotypes in its pages; however, for millions more worldwide readers, the novel is distinguished by its deeply moving sincerity. Set in the grinding poverty of rural Anhui, the novel opens as the humble farmer Wang Lung wakes on his wedding day. Rejoicing, he boils water for his ailing father and sprinkles in a few tealeaves, a luxury his father complains is “like eating silver.” But Wang Lung is too excited to care and even wastes precious water on washing himself for the first time in months. He hurries to the great House of Hwang, where his intended bride O-lan is a slave. Decadent opium addicts, the powerful Hwang family often sells off minor slaves as wives for poor men. Plain but loyal and uncomplaining, O-lan becomes Wang Lung’s companion, the mother of his much-desired sons, and at several crucial junctures, his salvation.

We follow the ambitious Wang Lung and dutiful O-lan from their wedding day through to their deathbeds. Although beautifully written, their journey is rarely pretty. The young couple is hardworking and scrimps and saves to buy small tracts of land from the debauched House of Hwang. Buck’s descriptions of O-lan’s pregnancies and deliveries are stark and painful even now. In a devastating famine, Wang Lung’s pernicious aunt and uncle commit cannibalism, while O-lan must secretly kill her hungry newborn girl. They abandon their home, beg by the roadside, and only a windfall saves their lives. But as Wang Lung regains his fortune, he also accretes a hubris and dissipation that once consumed the House of Hwang. Throughout the novel, Buck’s genuine investment in the emotional lives of her characters shines through against even the most determined critiques.

The Good Earth holds a special appeal for students of history. It was the best-selling American novel of 1931 and 1932, the darkest days of the Great Depression. Its sequel novel Sons (1932) and silver screen adaptation (1937) were also runaway successes. Moreover, the novel is a testament to the American expatriate world that thrived in prewar China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries, Pearl Buck (née Sydenstricker) grew up in China, spoke Chinese as her first language, and only at the age of forty-two came to live permanently in the United States. As her biographer Peter Conn emphasizes, throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Buck exerted “more influence over Western opinions about Asia than any other American”—with the possible exception of another American expatriate born in China, Time founder Henry Luce.

The Good Earth holds a special appeal for students of history. It was the best-selling American novel of 1931 and 1932, the darkest days of the Great Depression. Its sequel novel Sons (1932) and silver screen adaptation (1937) were also runaway successes. Moreover, the novel is a testament to the American expatriate world that thrived in prewar China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries, Pearl Buck (née Sydenstricker) grew up in China, spoke Chinese as her first language, and only at the age of forty-two came to live permanently in the United States. As her biographer Peter Conn emphasizes, throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Buck exerted “more influence over Western opinions about Asia than any other American”—with the possible exception of another American expatriate born in China, Time founder Henry Luce.

Finally, The Good Earth calls us to revisit a great American writer who fought for her beliefs in the face of dark international horizons and withering criticism—in both China and America. Indeed, most contemporary Chinese critics were privileged elites who found it offensive that international readers might define China by its unsophisticated farmers rather than the refined arts and literati culture of imperial China. A woman in a man’s profession, Buck boldly wrote from the viewpoint of Chinese peasants and underscored their resolution and dignity. True to this novel’s title, her work also champions respect for nature and its finite resources. She condemned Japanese imperialism and evangelical Christianity alike. In 1938, she urged the U.S. government to open immigration to European Jews and personally sponsored as many as the law permitted. Her critiques of Chiang Kai-shek and acknowledgement of Chinese Communist accomplishments drew a firestorm from hysterical Cold Warriors. She was an outspoken advocate for birth control, international adoption, and the rights of children with special needs (her daughter Carol suffered from Phenylketonuria, or PKU). And while The Good Earth racked up enormous sales, a Pulitzer Prize, and even eventually Buck’s Nobel, this engrossing novel is most profoundly a testament to the worth of underestimated human beings, whatever their creed, color, shape or size.

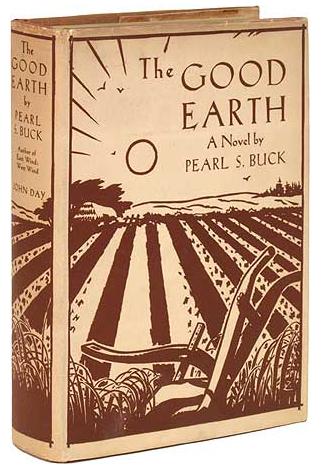

Photo Credits:

Between the Covers, Rare Book Inc., First Edition Cover of “The Good Earth,” released in 1938

www.betweenthecovers.org via Wikipedia