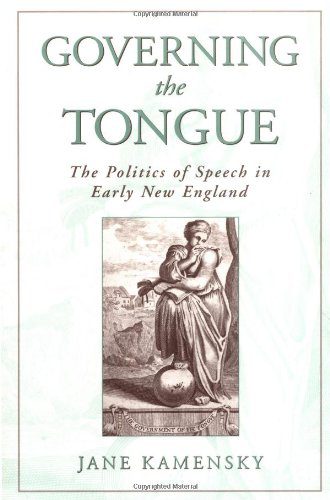

Governing the Tongue discusses the importance of verbal communication in seventeenth-century New England society. Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with Puritan religious beliefs and represented a way of directly interacting with God’s word. Right speech could represent a link with the divine, but incorrect speaking constituted a break with the natural order. Regulating oral communication presented both philosophical and practical difficulties that informed larger issues of social status and order, and Puritans thought uncontrolled speech could corrupt their fragile society.

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with Puritan religious beliefs and represented a way of directly interacting with God’s word. Right speech could represent a link with the divine, but incorrect speaking constituted a break with the natural order. Regulating oral communication presented both philosophical and practical difficulties that informed larger issues of social status and order, and Puritans thought uncontrolled speech could corrupt their fragile society.

Multiple social hierarchies governed correct speaking, including class, wealth, age, and gender, Kamensky’s most useful lens of analysis. A married woman, she argues, had to be a “goodwife,” supporting the head of the household, her husband. Women made up the majority of the nonconformist congregations and often held radical beliefs, most famously Anne Hutchinson, banished from Massachusetts Bay in 1638. For Puritan leaders, ungoverned speech equaled the threat of uncontrollable women, exemplary of the social disorder they feared. Women faced some of the harshest penalties for violating speech limitation. Ann Hibbens, for example, was brought to court for complaining too loudly in public about a dispute with male carpenters over the quality of their work, but the trial soon became an evaluation of Hibbens’ continued violation of right speech expectations and her failure to support her meek husband. Excommunicated in 1641, Hibbens was executed for witchcraft fifteen years later because of a “quarrelsome” tongue.

Kamensky also focuses on speech expectations among men, emphasizing the contested verbal domains of fathers and sons. Sons often found it difficult to establish patriarchal order in their own households while remaining verbally respectful to their fathers, exemplified by the case of John Porter, Jr., the only Puritan ever brought to trial for rebelling against his father. John, Jr. insulted and criticized his father repeatedly, failing to live up to high expectations in a society that valued the orderly transmission of status and property from father to son. Although John Porter, Sr. was one of the wealthiest men in Salem, his son died destitute after being taken to court for his disobedience. Kamensky contends that Porter’s parental disrespect echoes a larger struggle in New England during the 1660s, when generational tension between the founders and their children brought the issue of verbal respect to a head.

After illustrating the elaborate rules that governed women’s and men’s tongues, Kamensky convincingly argues for the decline of this system at the end of the seventeenth century. A falling away from original ideals for speech behavior, aided by the increased importance of the written word, paralleled the larger religious and intellectual declension of Puritanism. Discussing the witchcraft trials of the 1690s, Kamensky emphasizes the role of speech in the supposed activity of those practicing witchcraft, including curses and demonic possession, and in the public trials, which depended upon verbal testimony. The emotional and physical trauma of the accusations and executions in towns like Salem helped to debase the “currency of speech” for New Englanders. Numerous apologies from both accusers and judges failed to restore social order, as they once had done.

Kamensky acknowledges the difficulty of hearing Puritan voices in the available evidence. Writing a book about speech, solely using written records is a paradoxical and ultimately unachievable task, but she does an excellent job of finding examples of recorded speech in court records, sermons, and other writings.. Kamensky argues that although it is impossible to get back to the “hearfulness” of New England, the careful recording of court documents, responses to sermons, and quotations in diary entries brings us close to being able to hear the Puritans speak.

Kamensky’s study is a valuable account of the people and ideas responsible for the Puritans’ complicated relationship with the spoken word. She ably identifies the tension between free and governed speech, leaving the reader with the impression that, in Puritan New England, public speech could be both necessary and dangerous.

Photo credits:

George Henry Boughton (artist) and Thomas Gold Appleton (engraver), Puritans Going to Church, 31 March 1885

Library of Congress

You may also like:

UT professor of history Jorge Canizares-Esguerra’s DISCOVER feature on John Winthrop’s famous speech “City Upon a Hill.”