by Amber Abbas

Professor Masood ul Hasan was born in Moradabad in 1928. He completed high school from Hewat Muslim High School. His father was an employee of the Municipal Board. He completed his F.A. (Intermediate) from Government Inter-College, Moradabad. He studied in the Aligarh Muslim University from 1943 to 1947 where he completed his B.A. and M.A. in English Literature. He completed his Ph.D. in Liverpool while he was appointed as a Reader in the Department of English at AMU. He retired from AMU in 1988 after serving as Professor of English, Chair of Department of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts. He also served as the Proctor of the University. He continues to live in Aligarh, in Sir Syed Nagar.

I met Professor Masood ul Hasan first in July 2008, and I interviewed him a total of three times in 2008 and 2009 while I was living in Aligarh to conduct my dissertation research on the role and experience of Aligarh students in the freedom movement and the movement for Pakistan. He was extremely supportive of my project, and frequently introduced me to other senior and retired professors who had been his friends and colleagues for generations. I always looked forward to a visit and a cup of tea at his home during my stay in Aligarh!

I met Professor Masood ul Hasan first in July 2008, and I interviewed him a total of three times in 2008 and 2009 while I was living in Aligarh to conduct my dissertation research on the role and experience of Aligarh students in the freedom movement and the movement for Pakistan. He was extremely supportive of my project, and frequently introduced me to other senior and retired professors who had been his friends and colleagues for generations. I always looked forward to a visit and a cup of tea at his home during my stay in Aligarh!

Professor Hasan was also one of only a few students of the 1940s who was willing to speak about his involvement with the Muslim League in the 1945-46 elections. He frequently made sure that I understood that he regretted his involvement with the League and chalked it up to youthful enthusiasm, a desire for adventure, and naivete. He chose not to leave for Pakistan despite his involvement with the League and remained his entire career at Aligarh University as a professor of English.

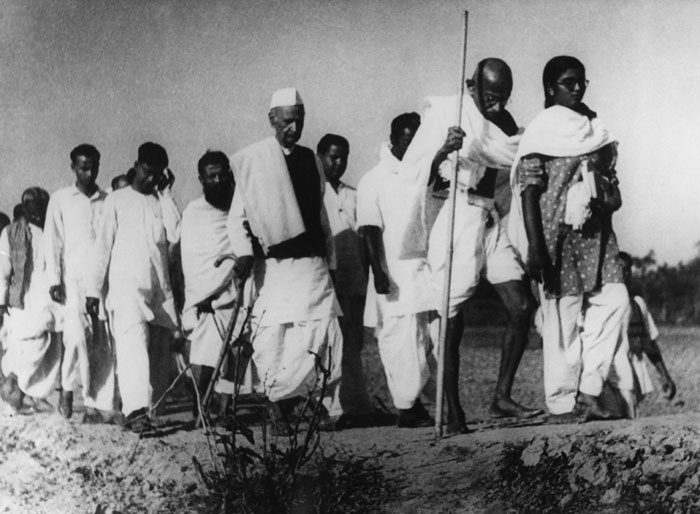

In this interview he describes his experience on the day of Gandhi’s assassination, a mere five months after the partition of the country. On that day, Masood ul Hasan was traveling from Aligarh to his home in Bhopal. He took a train from Aligarh to Agra and was to buy his onward ticket in the Agra Cantonment Station. When he sat in the train, he made a deliberate choice to avoid the “minority compartment,” a concession made by the railways to protect Muslims and other minorities in the wake of the partition violence when trains became sites of massacre. It was his “little assertion of self-confidence” to ride in the general compartment, clad in a sherwani – a typically Muslim coat that was a gesture of pride in his heritage but marked him as a minority. These choices would have been only slightly risky on any other day. On this day, however, as he stepped onto the train platform at Agra and found it deserted, Masood ul Hasan felt afraid. The news of Gandhi’s assassination created a difficult position for him. If a Muslim had killed Gandhi, all Muslims would be held responsible, and the violence of partition could be reignited. As he stood on the platform, terribly alone, in the city made famous by Shah Jahan’s majestic Taj Mahal, a monument to India’s Muslim heritage, he feared what might happen if he were unable to leave.

Luckily, the ticket collector took pity on him, arranged for a ticket and Hasan was able to depart for the safer environment of his home in Bhopal. He did not become a victim of violence on that day, but the fear he experienced speaks to the uncertainty that Muslims in India felt, especially when traveling through unfamiliar environments, in the early years after India’s independence. Whereas they were supposed to have the same rights and privileges as other Indian citizens, the trauma of 1947 was still fresh, and, especially when traveling, Muslims often feared for their safety.

Hasan’s narrative picks up on some familiar themes from other stories Muslims tell about this day. It is singular, it stands out in the memory; he, like others, is able to tap into his emotions and experience with remarkable clarity. Muslims almost without exception feared a Muslim assassin. After everything they had been through in 1947 and Gandhi’s selfless efforts to protect Muslims in places they were threatened, a Muslim assassin would unseat in one shot the tenuous but safe position of Muslims in early 1948. Everyone knew this, not just Muslims. And when it was revealed that the assassin was a fundamentalist Hindu, Muslims heaved a collective sigh of relief. No conservative Hindus were targeted or held responsible for the actions of Nathuram Godse. Muslims were spared, but one of their staunch allies was lost.

LISTEN TO THE ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW HERE

READ THE ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT HERE

Photo credits:

Amber Abbas, untitled portrait of Professor Masood ul Hasan

Author’s own via Not Even Past

Yann, Gandhi in Noakhali, 1946

Author’s own via Wikimedia Commons

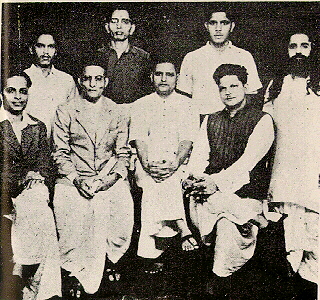

Unknown author, “Group photo of Hindu Mahasabha, the group accused of successfully staging Gandhi’s assassination. Standing: Shankar Kistaiya, Gopal Godse, Madanlal Pahwa, Digambar Badge (Approver), Guruji M.S. Golwalkar. Seated: Narayan Apte, Vinayak D. Savarkar, Nathuram Godse, Vishnu Karkare.” via Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

Voices of India’s Partition, Part III: Interview with Professor Irfan Habib

Voices of India’s Partition, Part II: Interview with Mr. S.M. Mehdi

Voices of India’s Partition, Part I: Interview with Mrs. Zahra Haider