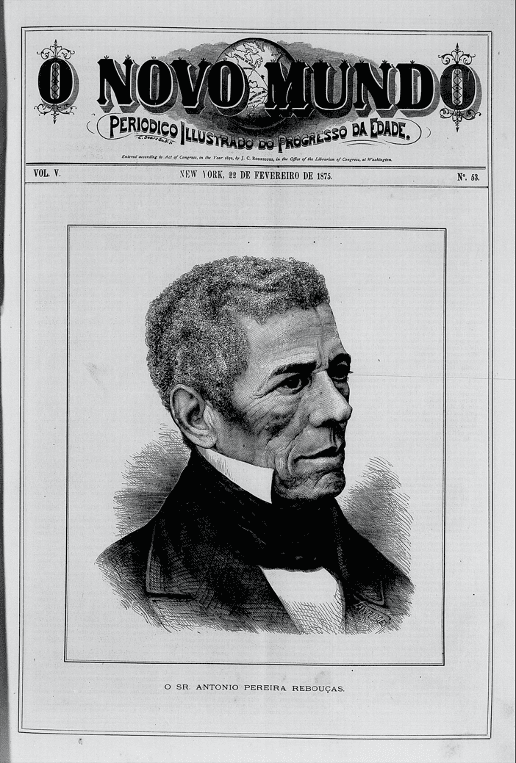

Like Borges, he spent his last years in a strange solitude: blind, dictating his last words. A life split between the practice of law and politics in nineteenth-century Brazil ended with a taste of failure and defeat—yet a life worth revisiting. Antonio Pereira Rebouças, the youngest child of nine, was born in Maragogipe, Brazil, in 1798. A mulatto born from a white Portuguese father and a free Black Brazilian mother, he benefited from his military participation in the struggle for Independence and rose to high levels in the intertwined, yet separated worlds of law and politics. Rebouças became a self-taught lawyer and a provocative politician despite the hindrance of his race in a slave society. His explanation of how this could happen would be, at the same time, his greatest achievement and the reason of his subsequent failures. “Race,” for Rebouças, did not matter, or at least it should not matter more than order, property, and the law.

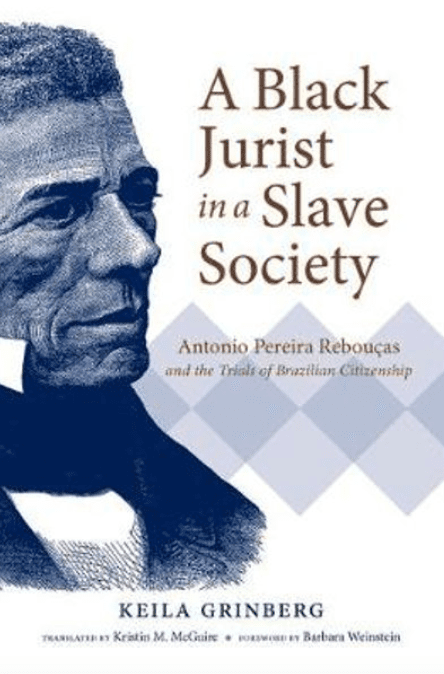

In A Black Jurist in a Slave Society, Keila Grinberg traces the life and works of Rebouças to explore how race, slavery, law, and politics worked in the complex, ever-changing context of early independent Brazil, and how they shaped ideas of law, citizenship, and liberalism. But Grinberg did not write a biography. She anchors her analysis in the life of Rebouças, his work as a congressperson and as a practicing lawyer in freedom trials (legal procedures where the concepts of freedom and property clashed) through his memoirs, court cases, and recorded speeches, while situating this in broader historiographical discussions of nineteenth-century Brazil. Rebouças’ work guides Grinberg through this clash when it took wider meanings in discussions on citizenship and liberalism, political and civil rights.

Race always played a role in shaping the outcomes in the life of Rebouças. Being mulatto restricted him from dinners and political positions; it raised suspicion and created endless rumors of resistance and rebellion he spent years trying to shut down. The specter of black violence followed him for the rest of his life. Yet Rebouças refused to put race at the center of his legal thinking and politics. Property and work belonged to no one, and as long as enslaved people and racialized bodies could rise to the top through effort and planning as he did, there was no reason to introduce it explicitly as part of the legal framework. In Rebouças’ mind, slavery did not entail an immoral, unacceptable system as long as anyone could overcome it. “Any pardo or preto can be a general,” he stated once, disregarding a world where it would be more difficult for them than from anyone else.

As Grinberg shows, Rebouças was not alone. In many ways—and sometimes against his will—Rebouças became a model for racialized figures in post-Independence Brazil. Formally a moderate speaker, legally a conservative thinker, his stances and ideas yield a striking portrait only when compared to renowned North American black intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass, who struggled and wrote for their collective freedom. Rebouças, in contrast, embraced the world he lived in and tried to change it via the mechanisms built into the system: law, politics, and the press. Like Borges, he lived the apparently contradictory life of a man of letters who is politically conservative. An avid reader and writer, he could not concede the structural difficulties others suffered. Yet, once put in context, it eventually makes sense. There lies the contribution of A Black Jurist in a Slave Society: to portray a man and his work as a product of his time.