Some of the most important documents for historians of Jewish history are documents that haven’t been saved at all. In fact, they’ve been discarded – into a closed storage space known as a geniza. This custom has its origins in Jewish law, which prohibits Jews from simply throwing away worn out or unneeded texts that contain the Hebrew name of God. To the great benefit of scholarship, Jews have often extended the precept to include all kinds of texts, sacred and profane.

The greatest treasure of this kind is the Cairo geniza, an enormous cache of some 300,000 documents or fragments discovered in 1896 in a synagogue in Old Cairo and brought to the attention of the great Judaica scholar Solomon Schechter. For a thousand years, Cairo Jews deposited texts and documents here that were no longer of use. Aside from the sacred texts – Hebrew Bibles, prayer books, tractates of the Talmud, etc. – there were shopping lists, marriage contracts, divorce deeds, leases, secular poetry, philosophical and medical works, business letters, account books, and private letters. Examining these documents has allowed scholars to paint a vivid and dynamic picture of Jewish society in the medieval Muslim Mediterranean. Today, anyone can go on line and see how scholars have dealt with the mass of material from this geniza, with photographs and translations of examples.

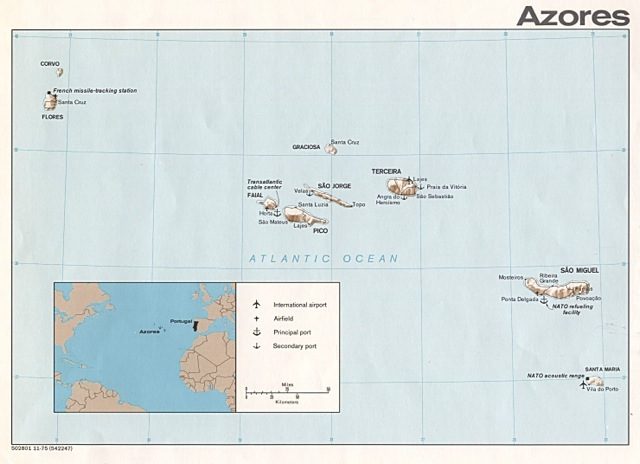

Fast-forward to 2014, when I joined my colleague Jane Gerber of CUNY Graduate Center to study material from another geniza, one that was far less important than the one in Egypt, but that had the attraction of never having been examined. With the indelible image of the two Scottish sisters in mind, we traveled to an abandoned synagogue in the Azores – an archipelago of nine islands in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, far from the historical centers of Jewish life. The trip was part of an effort organized and financed by the Azorean Heritage Foundation, whose mission is to bring to light the history of the now extinct community of Sahar Asamaim (Sha’ar Ha-Shamayim, or “Gate of Heaven”) that was established in the town of Ponta Delgada in 1821 by a group of Moroccan Jews. The community’s small synagogue, which has lain for years in disrepair, is now being restored, and the geniza materials – filling about 50 large filing boxes – have been recovered and deposited in the Municipal Archives of Ponta Delgada.

Map of the Azores. The geniza archive is stored in the Municipal Archives of Ponta Delgada on the island of São Miguel

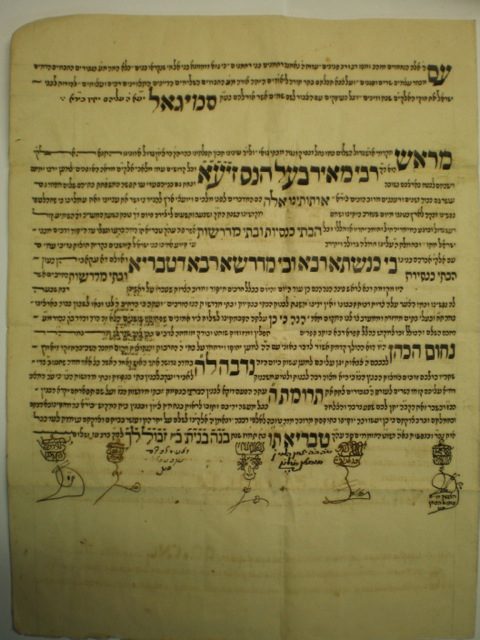

It’s too soon to know just how much the fragile, sometimes worm-eaten, occasionally mildewed material we found in this cache can tell us, but even at this early stage, the contours of the community have begun to emerge. Communal documents and commercial letters we examined confirm that this was a mercantile community dominated by a few wealthy families. It was quite traditional: the materials include many well-used Jewish sacred books, as well as phylacteries, prayer shawls, mezuzah scrolls, and other religious items. It was a distinctly North African community: the boxes contain documents signed by rabbis in the ornate Magrebi style, and members of the community had names like Bensaude, Zagorey, Bozaglo, Azulay, Zafrany, and Biton.

Yet the community was strongly oriented toward Europe. A commercial letter discussing trade in textiles mentions Liverpool, Bahia, Lisbon, and Hamburg as cities that were part of the author’s trade network. Hebrew books whose remains are in the geniza were imported or brought from Livorno, Vienna, Amsterdam, Paris, and Berlin. One of our favorite finds was a set of wrapping labels from packets of matzah (unleavened bread for Passover) imported from Manchester. The labeling, in Hebrew letters, had been carefully cut from the wrapping and placed in the geniza.

Among the materials we found were a number of appeals from the Holy Land, seeking funds for Jews living in the four cities Jewish tradition held to be holy – Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed. These petitions attest to the strength of the ties the Azores community maintained with a Jewish center that had no commercial importance but immeasurable spiritual significance.

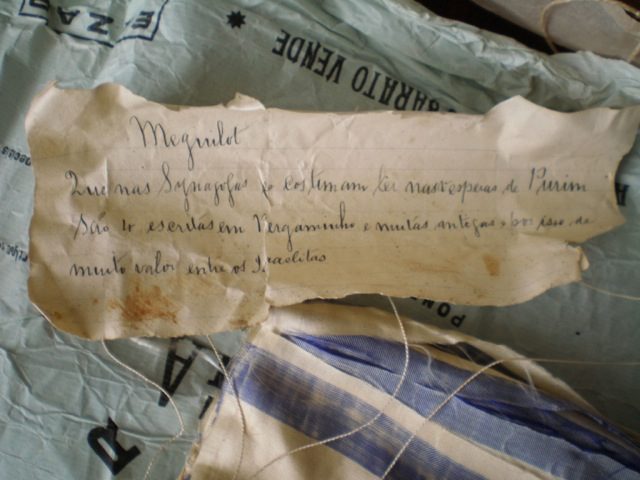

The community thrived for generations, but by the 1940s its numbers had so dwindled, through emigration and conversion, that the synagogue did not have a minyan, or quota, of ten adult men for Sabbath prayer. Today, there is only one person left from the community, Jorge Delmar, who holds the key to the Jewish cemetery. He has carefully saved Jewish documents and ritual items preserved in his family, though he has little idea of what they are. He showed us, for example, a set of three tiny Scrolls of Esther. An undated note left with the scrolls by their owner, for the benefit of whoever might come across them, offered poignant testimony of the disappearance of a community and its culture. The note explained that these were “Meguilot [scrolls] that they were accustomed to read in the synagogue on the eve of Purim. They are written on parchment and they are very old and for this reason they are of great value to the Israelites.”

You may also like:

Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza

S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 5 volumes

Miriam Bodian, A Dangerous Idea

Miriam Bodian, Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam (1999)