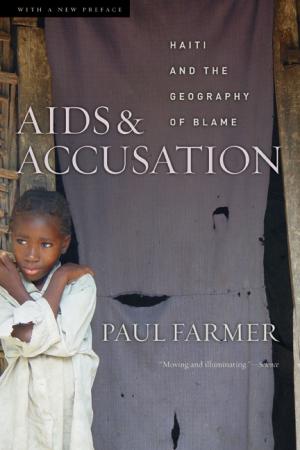

by Blake Scott

In 1983, the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia announced that there were four major risk groups for AIDS in the United States – homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin-users, and Haitians. The report acknowledged that each of the four groups – widely known as the “Four-H Club” – contained many individuals who were not at risk for AIDS. In the early years of the epidemic, however, those exceptions meant little to the public. AIDS was a new, mysterious disease and these people were its supposed carriers. The warning, in the end, may have caused more harm than good, intensifying paranoia and discrimination.

While all four groups experienced the stigma of accusation, there was something particularly arbitrary about the ‘Haitian’ risk pool. It was the only risk group based on nationality rather than specific behavioral factors. Why were all the citizens of Haiti included in the CDC warning? In his well-crafted book, Paul Farmer takes “a geographically broad and historically deep” approach to explain the roots of the AIDS accusation afflicting the Haitian community.

While all four groups experienced the stigma of accusation, there was something particularly arbitrary about the ‘Haitian’ risk pool. It was the only risk group based on nationality rather than specific behavioral factors. Why were all the citizens of Haiti included in the CDC warning? In his well-crafted book, Paul Farmer takes “a geographically broad and historically deep” approach to explain the roots of the AIDS accusation afflicting the Haitian community.

Leading up to the official warning, the media and a handful of prominent scientists in the U.S. had erroneously concluded that Haiti was the original source of AIDS in the Americas. As Farmer convincingly argues, though, the Haitian origin theory represented a “systematic misreading” of both epidemiology and history. The false accusations that swirled around the Haitian community, he explains, drew on a long history of racism and ethnocentrism.

Over the course of the 1980s, Farmer, a medical doctor and anthropologist at Harvard University, carried out extensive ethnographic fieldwork in Haiti, while at the same time, offering medical services to rural communities. In his writings, Farmer combines medical and anthropological knowledge to explain how both international and local forces shaped disparate responses to the epidemic.

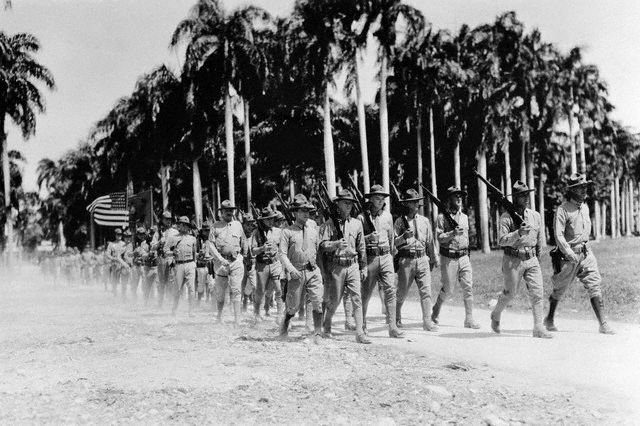

U.S. troops marching during the occupation of Haiti, 1915, via Wikimedia Commons.

U.S. troops marching during the occupation of Haiti, 1915, via Wikimedia Commons.

The book is made up of highly readable essays that allow the reader to approach the story from several angles – from Haitian community dynamics to larger medical debates to transnational economic and political issues. In one essay, for example, Farmer narrates the local history of the village of Do Kay to illuminate how poverty and cultural beliefs, such as sorcery, helped to direct responses to the disease. In another section, he explores the intersections between epidemiology and history to explain how HIV most likely arrived to Haiti via North American tourists. The arrival of AIDS, he concludes, was linked to Haiti’s historical and continually evolving role in a regional economy dominated by the United States.

Haiti after the earthquake. Photograph by Eva Hershaw.

Haiti after the earthquake. Photograph by Eva Hershaw.

Farmer offers a compelling argument for why medical professionals need to better understand the histories and cultural practices of the people they hope to help, at home and abroad. Haitian counter-theories, which vehemently blamed North American imperialism for the arrival of AIDS, originally baffled U.S. medical doctors and scientists. A greater awareness of the history of U.S.-Haitian relations would have led to a more sympathetic and likely, a more effective medical response. In short, anyone interested in learning how history and culture affect societal responses to disease will find Dr. Farmer’s book well worth their time.

For those interested in learning more:

The Agronomist. In this documentary, award-winning director Jonathan Demme profiles the life of Haitian journalist and radio pioneer Jean Dominique. Through the life of Dominique and his family, The Agronomist offers a compelling portrait of Haiti in the second half century of the twentieth-century.

Paul Farmer’s Haiti After the Earthquake. Dr. Farmer offers an on-the-ground account of the most recent earthquake in Haiti, discussing its aftermath and recovery projects, past, present, and future.

Mary A. Renda’s Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915-1940. Professor Renda explores the cultural dimensions of U.S. contact with Haiti during the 1915 intervention and its aftermath. She shows that what Americans thought and wrote about Haiti during those years contributed in crucial and unexpected ways to an emerging culture of U.S. imperialism.

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Professor Dubois weaves the stories of slaves, free people of African descent, wealthy whites, and French administrators to explain how the Haitian Revolution became a foundational moment in the history of democracy and human rights.