By Kyle Walker

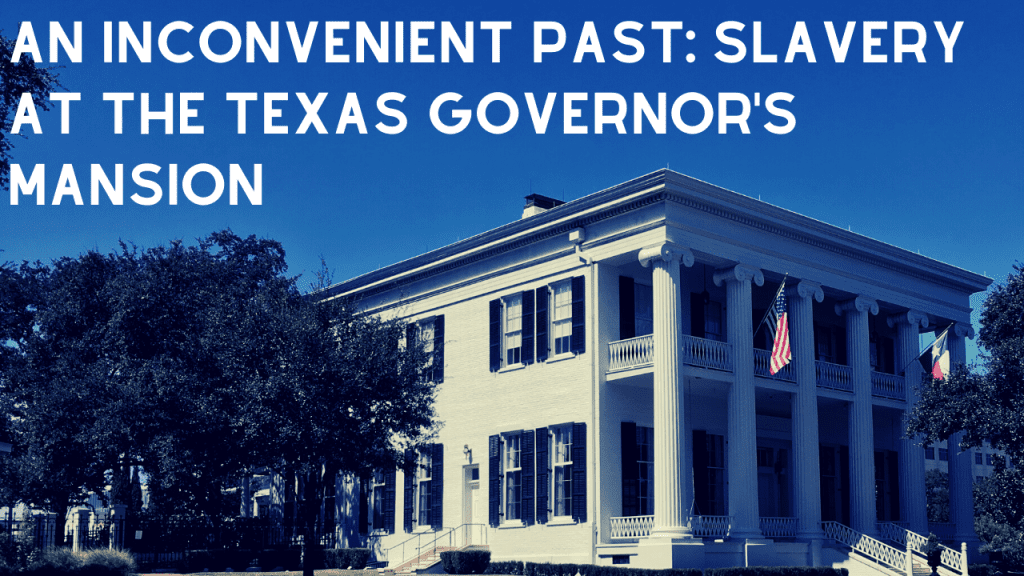

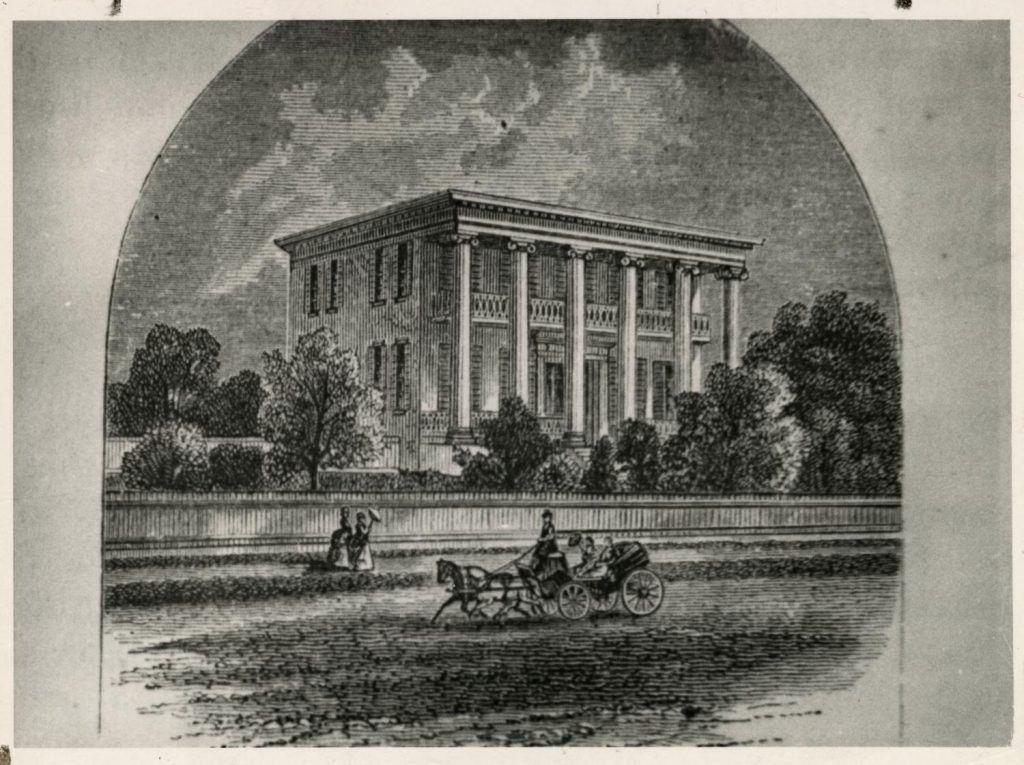

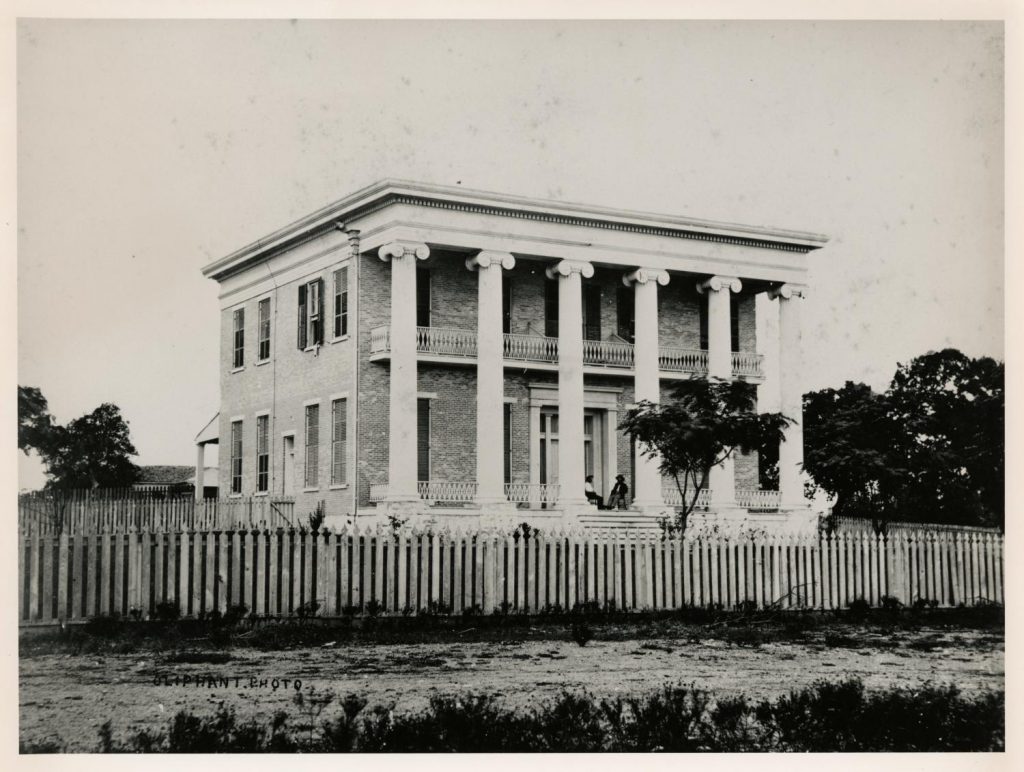

Completed in 1856, the Texas Governor’s Mansion is the oldest executive residence west of the Mississippi River and the fourth oldest continuously occupied executive residence in the US. Between 1856 and 1865, eight men would serve as the Governor of Texas and call this residence home. While the histories of these men and their families are well documented, little is known about the lives of the other occupants of the Mansion, the enslaved men and women who belonged to these Texas Governors.

My research at Texas State University has focused on the history of enslaved African Americans at the Texas Governor’s Mansion. The topic of slavery at the Texas Governor’s Mansion first came to my attention in the spring of 2019. From 2013-2019 I worked for the Texas State Preservation Board in various roles but primarily as a gallery assistant at the four historic sites that the agency preserves and operates. While concluding a tour at the Mansion in April 2019, a visitor asked me where the slaves of former governors lived while at the Mansion. I was dumbfounded, not only because I did not know the answer to their question, but because I had never stopped to ask that question myself.

Reflecting on the visitor’s question raised so many more questions for me. Had the subject of slavery at the Mansion ever been explored before? Why had the history of slavery at the Governor’s Mansion not been explored in greater detail? Why did the Preservation Board decide not to include this aspect of the mansion’s history in their tour material or at least inform their guides about how to interpret this difficult history? Had other cultural institutions such as the Texas Historical Commission, Friends of the Governor’s Mansion, Austin History Center or George Washington Carver Center in Austin explored this subject through publications or exhibits?

The history of slavery at the Texas Governor’s Mansion is a little known and rarely discussed topic at the state’s executive residence today. The tours of the historic home that are offered by the Preservation Board or the Friends of the Governor’s Mansion (a private non-profit organization which manages the home’s collection of historic furniture and artwork), make no mention to the presence of enslaved individuals who worked at the residence between 1854-1865. Brochures and guidebooks available to visitors make no reference to the presence of slaves at the residence although a few scholarly publications, including Kenneth Hafertepe’s Abner Cook: Master Builder on the Texas Frontier (1992) and James Haley’s biography of Sam Houston (2002), do discuss slaves at the site before the end of the Civil War. No interpretive signs stand outside the home, nor are there any exhibits on display in any state, city or county museum in Austin that discuss the role of slavery in the history of the state’s executive residence.

Despite the scholarly work that has been produced about the history of the Texas Governor’s Mansion, the careers of these governors and the lives of their spouses, there exists no substantial analysis of slaves at the Governor’s Mansion. They are seldom talked about or mentioned in publications. When they are, their status was often referred to as that of “servants.” Although more recent publications do at least acknowledge the presence of slaves, little attention has been given to the extent of slavery at the site.

My research into the history of the Mansion has confirmed that up to thirty-eight slaves may have resided at the Texas Governor’s Mansion between 1856 and 1865. I have also shown that slave labor was employed in the construction of the state’s executive residence. The slaves of Texas Governor’s primarily resided in the servant’s quarters above the home’s detached kitchen, located off the back (west) of the home. Some Governors with larger numbers of slaves housed some of them in the stable and carriage house behind the Mansion. A few Governors even allowed some of their slaves to reside in the unused rooms of the house and the slaves of Governor Pendleton Murrah (1863-1865) were left to care for the residence when the Governor abandoned the Mansion after the surrender of the Confederacy.

In my research I also set out to determine if other cultural institutions in Austin had investigated the subject of slavery at the Governor’s Mansion. As I expected, the subject was a topic that had been largely neglected by the Preservation Board, the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, the Austin History Center, the George Washington Carver Center and even the Texas Historical Commission. This was even though exhibits and historic plaques had been produced focusing on the slave narrative of Jeff Hamilton, a slave of Sam Houston.

What explains this lack of attention? As a historic site, the Texas Governor’s Mansion is an administrative conundrum. It is administered by four state agencies; the Texas State Preservation Board, which preserves, maintains and operates the visitor services of the Mansion; the Texas Historical Commission, which oversees the historic integrity of the home; the Texas Department of Public Safety which provides security for the First Family; and the Office of the Governor. The Governor of Texas is a sitting member on the State Preservation Board, along with the Lieutenant Governor and Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, who all have a direct say in the preservation and interpretation of the state’s executive residence. This political connection to the state’s top executives has likely caused the Preservation Board to tread lightly when interpreting difficult history such as slavery and the Confederacy at the four historic sites they operate in Austin, for fear of political backlash not just from state politicians but also their constituents.

It is clear, however, that slavery and enslaved individuals were a significant feature of the Texas Governor’s Mansion throughout its first decade. Despite the controversial nature of the subject and the political sensitivity of the Governor’s Mansion, the continued lack of interpretation or acknowledgement of the subject is, I believe, a disservice not only to the memory of the enslaved persons that once called the Mansion home, but to the greater heritage of African Americans in Austin and the wider state of Texas.

With thanks to Dr Kenneth Hafertepe for his valuable comments.

Kyle Walker is a recent graduate of the Public History program at Texas State University. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin in Anthropology and Geography. As an undergraduate, he participated in archaeological field schools in central Texas and Belize as well as interning with the Texas Historical Commission’s Archaeology Division. As an intern Kyle assisted in cataloging artifacts from the seventeenth century shipwreck of the LaBelle and conducted research for Presidio La Bahia in Goliad Texas. Before enrolling at Texas State, he worked for five years with the Texas State Preservation Board in Austin at historic sites such as the Texas State Capitol, the Capitol Visitors Center in the Old Land Office, the Texas Governor’s Mansion and the Texas State Cemetery. As a graduate student his studies have coincided with his previous work experience, focusing on local and community history, architectural history, historic preservation, museum management, exhibit design, digital history and material culture. In the coming year he hopes to publish his graduate research in an academic journal and is currently assisting the Longhorn Alumni Band in research for a photographic history of the Longhorn Band to be published in 2022. At present, Kyle works as an Administrative Assistant for the Department of History at UT.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.