In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

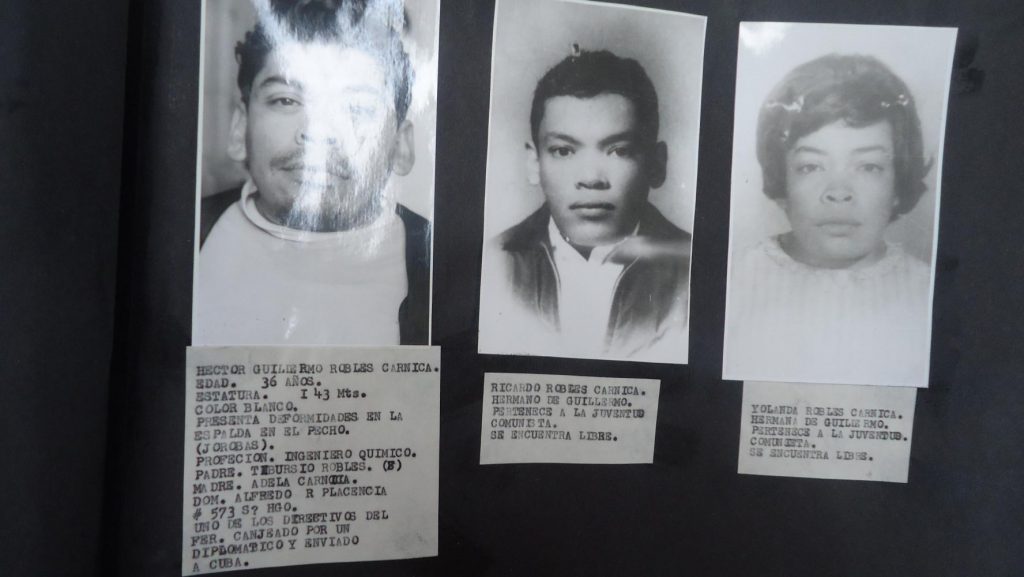

Archivos de la Represión is a civil society project aimed at promoting the right to truth and the memory of Mexico’s period of repression and systematic violence by the state between 1950 and 1980. In collaboration with ARTICLE 19, an international human rights organization, Northwestern University, El Colegio de México, and others, “Archivos de la Represión” is working to make 310,000 official documents available to the public through their digital archive. “Archivos de la Represión” will present at the 2022 Lozano Long Conference titled “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives” on the “Public, Access, and the Archival Dimensions of Digital Humanities” panel. The conference, held in honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, will take place in a hybrid format with pre-circulated papers and pre-recorded presentations of the panels with live Q&A on February 24-25, 2022.

The growth of digital humanities has broadened our understanding of and use of archives. As new technologies and methods become available, so do discussions about accessibility. The tools and technical standards available in digital humanities contribute to a broader, more public use of scholarship, which has resulted in new connections and the ability to make previously inaccessible information publicly available. Archivos de la Represión is an example of a digital humanities project initiated by Mexican civil society in response to the government’s failure to recognize a fundamental human right in the early twenty-first century: the right to information and historical truth. Organizers conceived of the project in the aftermath of the Mexican government’s 2015 censure of documents containing evidence of human rights violations from the Dirty War (1968-1982).[1]

With so many unanswered questions, Archivos de la Represión digitized 310,000 previously available documents containing evidence of human rights violations. This was done with the assistance of historians and official truth commissions. Archivos de la Represión is currently in the process of categorizing the documents using the Dublin Core metadata standard, which has resulted in more detailed document descriptions than was previously available.[2] As of October 2020, 46,364 documents had been cataloged and made accessible via their digital library, which was developed in collaboration with ARTICLE 19, an international human rights organization, Northwestern University, El Colegio de México, and others. By creating a digital library and archive, Archivos de la Represión reopened a window into the Mexican state’s logic of violence and human rights violations. The digital archive allows users to identify connections between events, create new narratives, and gain access to historical memory. This project has brought the Mexican public closer to the truth and memory promised to them 19 years ago.

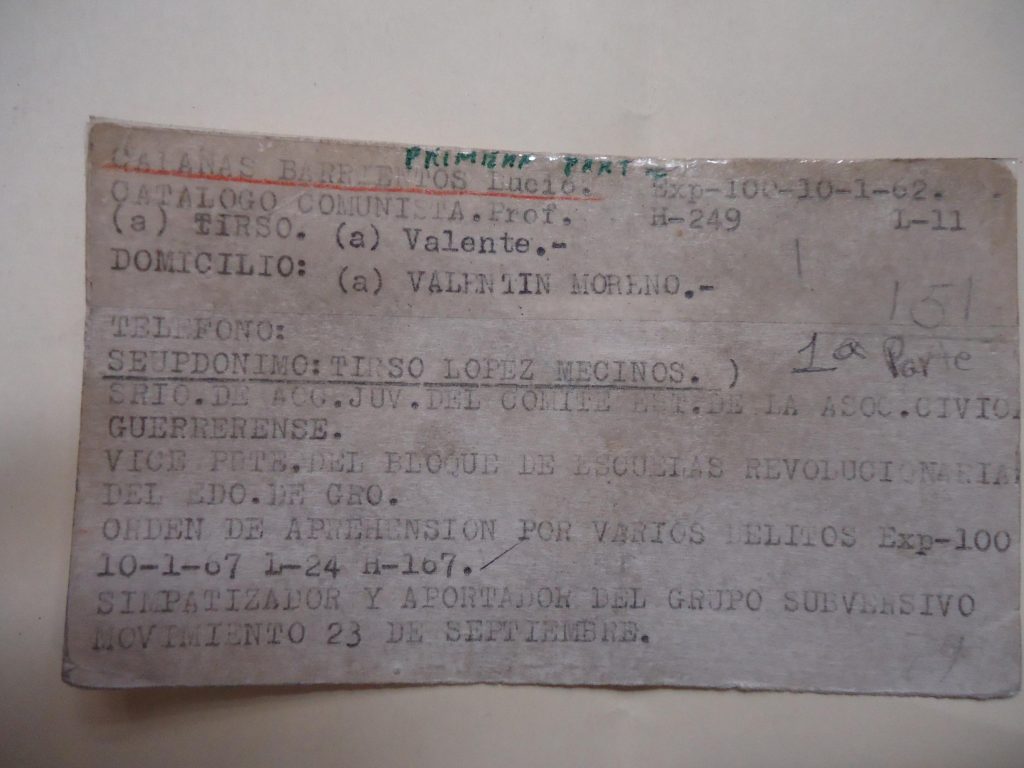

In 2002, the passage of the Ley Federal de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública guaranteed the Mexican public access to government information following years characterized by a lack of transparency.[3] Government documents would be housed at the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) located in Mexico City. President Vicente Fox Quezada (2000-2006) stated that the records would be used to not only reconstruct Mexican history but also to hold organizations and individuals accountable for human rights violations.[4] The Mexican government owed an explanation to its citizens regarding the events of the Dirty War, which resulted in the systemic torture and disappearances of over 1,200 people. This violence was the outcome of internal conflict between the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and left-wing citizens. Government agencies such as the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS), Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales (DGIPS), and the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional created surveillance files on students, Communist Party members, guerilla groups, or anyone else deemed suspicious.[5] In 2015, the documents housed at AGN became inaccessible with the new Federal Archives Law passed in 2012, and the Mexican public was once again left with unanswered questions as to what happened during this period of violence.

The 2002 Ley Federal de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública legislation was not the first time the Mexican government attempted to improve its transparency. In 1977, Article 6 of the Mexican constitution was amended to address the right to government information.[6] In that same year, the AGN was relocated to the Palacio Negro de Lecumberri, a formal prison that held political prisoners from the Dirty War.[7] However, even in these decades of ostensibly unrestricted access and improved transparency, visitors struggled to identify the documents they were looking for. According to the Human Rights Watch, the collections made available after 2002 were frequently poorly cataloged, making it impossible to determine which ones should be processed first.[8] Inconsistent accessibility has been attributed to a lack of government funding and purposeful obstacles created by the AGN. With no finding aids or indexes to consult, visitors had to submit a request to the archive staff with subjects of interest. The staff member would then choose which objects to bring to the researcher. This is a stark contrast to Archivos de la Represión’swork that allows users to search and filter documents by names, organizations, or government officials.

While the access to information law has been amended over the years to enhance transparency and accountability, the government has made little effort to enforce information freedom, transparency, or accountability. The result is a disconnect between the government’s assurances and the AGN’s ability to catalog materials and meet demand. The passage of the Federal Archives law in 2015 reclassified many documents from the Dirty War that were thought to contain confidential information and could remain classified for up to 70 years. To view documents, visitors now had to submit information requests to the government and hope that they were approved, with the added disadvantage that the documents could be censored to protect confidential information.

Archivos de la Represión empowers citizens to not only investigate the various human rights violations and crimes committed by the state but also to ask questions and support Mexican civil society in creating new narratives of its difficult past. Their digital library has made 310,000 digitized historical documents available to the public, and they are working towards cataloging the entire collection. Through their meticulous work, users can navigate their collection and search by names, organizations/institutions, or government officials. Additionally, they aim to provide more context to the document such as topics, dates, geographical locations. All of this information is hosted through a digital humanities tool, Omeka, an open-source content management system. This additional information, which was not provided by the AGN, gives users the tools to make connections between events in ways that they might not have been able to before.

Archivos de la Represión acknowledges that the documents included in their project do not contain the entire truth and that much violence was not documented, or only partially documented. What the documents do offer is to the opportunity to see how “the Mexican State conceptualized political dissidence, the ways in which it fought them, and the logic of violence that it imposed and that configured practices that violate human rights, including crimes [by the] State”.[9] By cataloging and contextualizing documents, Archivos de la Represión does what the AGN and Mexican government have not done: organize, disseminate, preserve, and return the right to information.

Janette Núñez is a third-year dual-degree master’s student at UT Austin in Latin American Studies and Information Studies with a goal of becoming a librarian. Her research examines the intersections of archives, collective memory, and human rights. Specifically, she studies the State Archive in Mexico, tracking information policies that have impacted the right to information. She is currently a Graduate Research Assistant with Special Collections at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, where she has prepared exhibitions, finding aids, and metadata for the Benson Rare Books Collection.

[1] ARTICLE 19 México. “Article 19 Presenta: Archivos De La Represión.” Facebook Watch. ARTICLE 19 México, November 21, 2018. https://ne-np.facebook.com/Articulo19/videos/292246698060848/.

[2] “Notas Metodológicas · Biblioteca Digital De Los Archivos De La Represión.” Archivos de la represión. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://biblioteca.archivosdelarepresion.org/page/metodologia.

[3] “Federal Transparency and Access to Public Government …” Accessed November 22, 2021. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB68/laweng.pdf.

[4] Evans, Michael. Freedom of Information in Mexico, nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB68/index3.html.

[5] “Fifty Years after Tlatelolco, Censoring the Mexican Archives: Mexico’s ‘Dirty War’ Files Withdrawn from Public Access.” Fifty Years After Tlatelolco, Censoring the Mexican Archives: Mexico’s “Dirty War” Files Withdrawn from Public Access | National Security Archive. Accessed November 17, 2021. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/news/mexico/2018-10-02/fifty-years-after-tlatelolco-censoring-mexican-archives-mexicos-dirty-war-files-withdrawn-public.

[6] “Article 6.” The mexico project. Accessed November 14, 2021. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/mexico/.

[7] “National Archives of Mexico.” ALA Archivos, July 17, 2019. https://www.alaarchivos.org/national-archives-of-mexico/.

[8] “III. Transparency: Ending the Culture of Official Secrecy.” Mexico: Lost in Transition: III. Transparency: Ending the Culture of Official Secrecy. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/reports/2006/mexico0506/3.htm.

[9] “Memoria y Verdad.” Archivos de la Represión. Archivos de la Represión. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://archivosdelarepresion.org/.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.