By Tiana Wilson

This article first appeared in Perspectives on History. The original can be accessed here.

It’s been nearly a year since COVID-19 forced many states to shut down and more than a year since I last stepped into an archive. As a fourth-year PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, I am writing a dissertation on late 20th-century women of color feminist organizations in the United States. My archives include university collections housed at Smith College and Duke University; public repositories located in New York, Alabama, and Washington, DC; and local museums such as the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. These diverse research facilities vary in degrees of funding and technical resources, which has made it extremely challenging to access certain materials during the pandemic. Despite this disruption in my research plans, I found ways to make progress on my dissertation. In order for me to stay on schedule and graduate on time, I had to prioritize flexibility, creativity, and collectivity in this new phase of dissertating.

By August, it was evident that archival facilities would be closed for the 2020–21 academic year or that their staffs would work remotely. My first plan of action involved meeting with my dissertation chair and department graduate adviser to discuss how the pandemic would impact my time to completion. In these conversations, my graduate adviser encouraged me to reevaluate the scope of the project, which could entail reducing the number of chapters I planned to write. Funding an additional year in the program was also a serious concern for my cohort members and me. Many of us, unless documents are available in digital collections, cannot conduct new research for our projects while archives remain closed.

My adviser offered a strategy for making the most of this year. She recommended that I begin writing with the materials I had gathered during preliminary research trips. Instead of following my department’s suggested five-year completion plan, which included one year researching and then the following years writing, I had to create my own schedule of researching and writing simultaneously. Developing a more flexible process also required me to become comfortable with writing incomplete chapters with the intent to add more content as I obtain new sources. With this plan I run the risk of having to substantially rewrite, if I draw different conclusions as I obtain new source material. Yet this process of rewriting and producing multiple drafts as my source base expands is necessary to accurately portray the histories of women of color, and can be productive for my intellectual growth.

I had to become more creative in my research practice.

I also had to become more creative in my research practice. My committee chair suggested that in addition to ensuring I was on each research facility’s email listserv, I also should inquire about the cost of digitizing sources, especially at university and national libraries, which often have more resources. These two tips were useful for staying updated on different archives’ opening status and acquiring materials without traveling. Following this advice, I learned that three of the facilities I was planning to visit were closed for the next academic year. Yet, these same libraries and centers allowed me to use my library grants for photocopying sources that I needed immediately. While I am fortunate to have this option, the process of obtaining digitized documents could take up to four months and, depending on the source, there may be copyright issues. Furthermore, the option to digitize materials is not available from my other archives due to limited staff and funds, delaying my ability to obtain new sources and pushing back my timeline for writing chapters. In the meantime, I am revisiting secondary sources on my topic and sharpening my research questions.

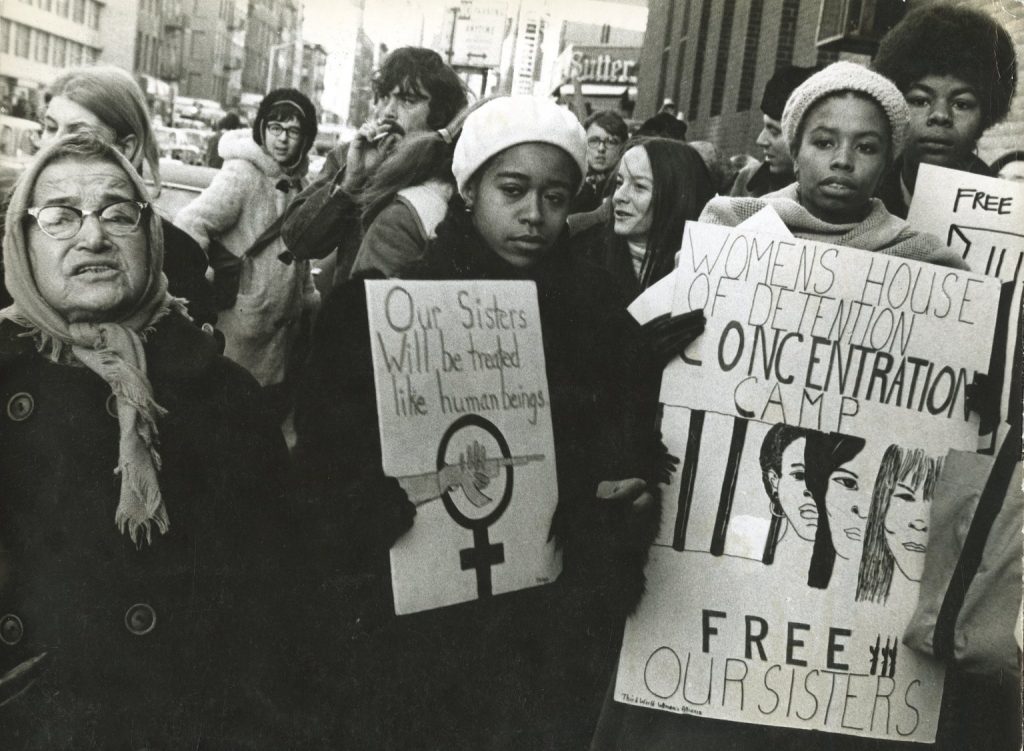

Third World Women’s Alliance, September–October 1971. Source: The Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

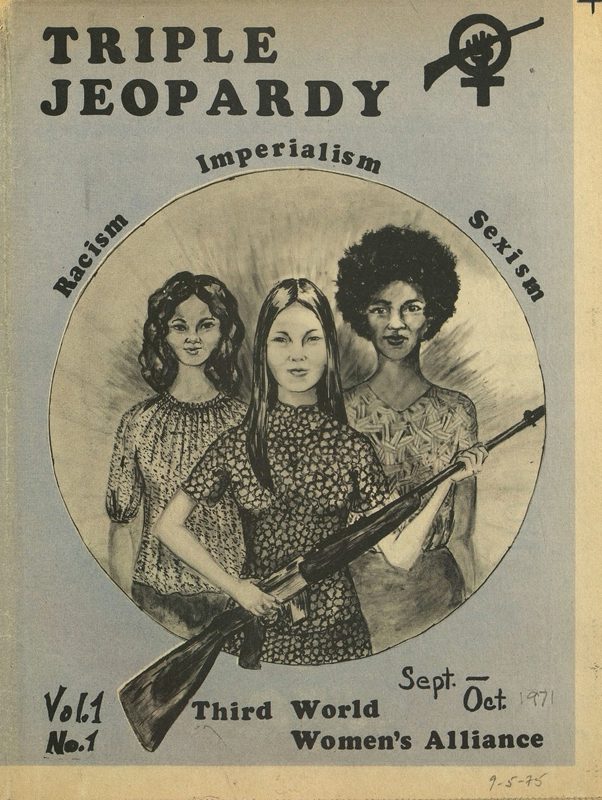

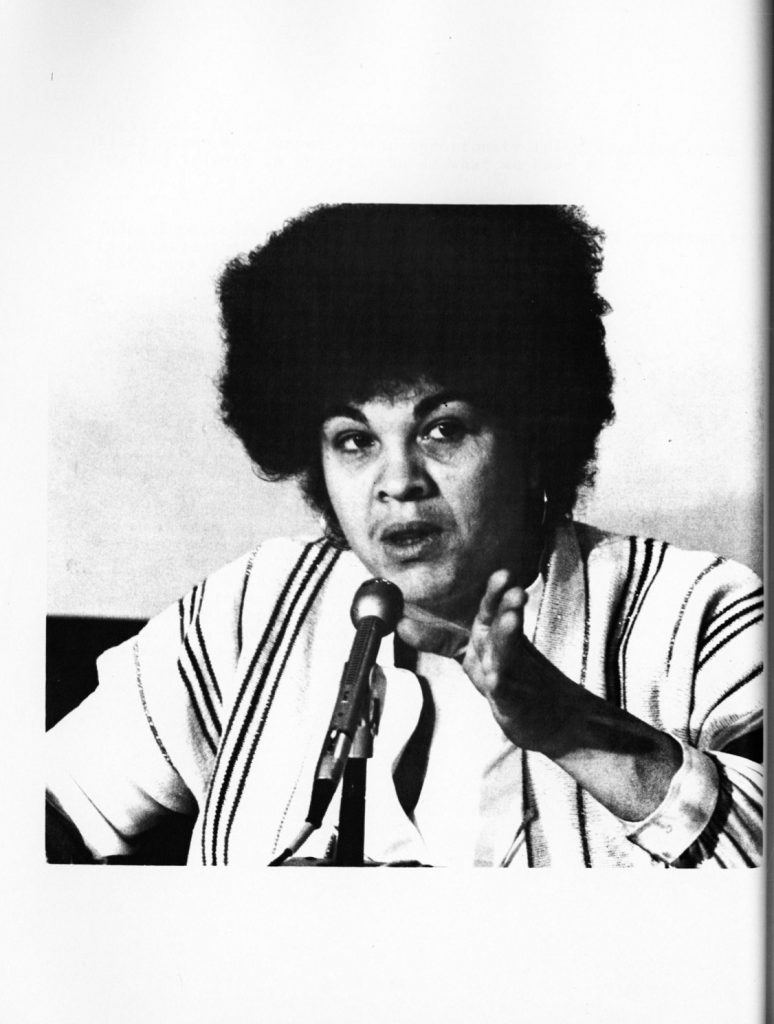

Founding member of the Third World Women’s Alliance, Frances Beal. Source: Blandford, Virginia A, Mary Alexander Walker, Howard University, and Institute for the Arts and the Humanities, eds. Black Women and Liberation Movements. Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Arts and the Humanities, Howard University, 1981.

Academics are accustomed to working independently, often isolated from others. But during the pandemic, I have found a more collaborative style of research essential to my progress. I benefited from pre-existing relationships, in which scholars connected me with other graduate students from different programs and at various stages of their careers. Although some group-sharing initiatives sprung up in response to COVID-19 (such as SHAFR’s Archival Records Discussion Group), I was not aware of them at first. Instead, I utilized collegial networks to pool resources for alleviating photocopying costs. This strategy could help those who were not awarded library grants, exceeded departmental research funds, or lacked financial support altogether. To forge such connections, you could create a shared Excel sheet with other graduate students in your department that lists archives you need to visit, or among graduate students working on the same topics at other universities. Those with overlapping archives can work together to acquire sources. If one student plans to visit before others or has a library grant that can be used for copies and has extra funds, the students can work together to obtain what they all need. (But check with each archive to be sure that you are not violating their policies or terms of a grant.) I am currently working with graduate students from other universities to share primary and secondary sources with one another. The pandemic has brought out a new collective research process that I will carry with me, even when travel restrictions are removed.

The pandemic has brought out a new collective research process that I will carry with me, even when travel restrictions are removed.

Another avenue to explore while engaging in collaborative research is contacting scholars who are working on a similar topic or historians who previously published an article or book on any aspect of your dissertation. This would most likely require emailing the authors of your secondary sources, detailing your project, and asking if they are willing to share primary sources that could be relevant for your study. Some advisers may oppose this tactic, fearing the real possibility of academic theft, so I would suggest you consult with a mentor before taking this step. However, I had a positive experience with this strategy, and I would encourage other students and faculty to willingly share sources with one another. Collective research is not threatening and has been essential to my productivity during the pandemic. As one of my mentors always reminds me, two people working with the same documents will have two separate analyses and may come to different conclusions.

During this pandemic, I have adjusted my expectations for the writing and research phases. Unlike previous cohorts at UT, I will not have the opportunity to conduct all of my research at once. Instead, I continually assess my project’s feasibility and must be content with writing sections of my dissertation with the assumption that I will fill in the gaps at a later stage. Furthermore, I am exploring new research directions for my project to utilize the vast number of digitized sources already accessible to the public and the resources that collaboration with other scholars has brought my way. Though the pandemic has forced me to reevaluate my plans, the lessons I’ve learned about being flexible, creative, and collaborative are ones I will hold onto throughout my career.

Tiana Wilson is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at UT Austin with a portfolio in Women’s and Gender Studies. Her broader research interests include: Black Women’s Internationalism, Black Women’s Intellectual History, Women of Color Organizing, and Third World Feminism. More specifically, her dissertation explores women of color feminist movements in the U.S. from the 1960s to the present. She is writing the first comprehensive study on the Third World Women’s Alliance, tracing their intellectual and organizing legacy in the US and abroad. Centering Black women and other women of color as leading thinkers, Wilson’s dissertation excavates the making of successful multiethnic and multiracial solidarity practices. Her project has been supported by the Sallie Bingham Center, Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics, Smith College Libraries, and the Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice.

This article first appeared in Perspectives on History. The original can be accessed here. Images sourced from the author were added for this reprint.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.