From the Editors:

“Picturing My Family” is a new series at Not Even Past. As a Public History magazine, we aim to make History more accessible by publishing research features and other articles. But of course, History doesn’t reach us solely through words. It lives on in images, too. A good photograph transmits as much information as a line of text, and it does so in an extraordinarily evocative way. Dispensing with description, photography brings us face to face with the past. Visual cues can stimulate our sensory imagination and present us with surprising new details, encouraging us to ask questions, to dig deeper, and to think like historians.

Our concept is simple. We invite Not Even Past readers to:

• Send us a photograph of a family member or ancestor. The photograph doesn’t have to be old; it could be from any period. The subject can be one of your grandparents, a cousin, a distant relative – anyone whom you count as part of your family.

• Tell us in less than 250 words what the image shows and why it’s meaningful for you and your family. If you wish, you can set the photo in historical context, too. But that isn’t necessary.

If you are interested in submitting something for this series, please click here.

In this instalment of “Picturing My Family,” current NEP Associate Editor John Gleb presents a photograph of his paternal grandfather. The photograph helps illuminate the sweeping global context of World War II; the accompanying texts tells a moving family story.

My Grandfather’s World War II Odyssey

By John Gleb

Borys Gleb, my paternal grandfather, was born in 1925. He grew up in what was then eastern Poland; today, it’s part of Belarus, thanks in part to a series of geopolitical shocks that changed my grandfather’s life. In 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, starting World War II in Europe. A prearranged treaty gave the USSR permission to occupy the eastern half of Poland, and as a result, 16 days after the German invasion, Soviet forces crossed the Polish border from the east, seizing control of the town where my grandfather lived. The next year, he and his family was deported to a work camp north of Moscow.

In 1941, my grandfather’s life changed again after Germany launched a surprise invasion of the Soviet Union. The invasion’s consequences were horrific, but it also opened up a lifeline for young men like Borys: a new Polish army, eventually placed under British command, began recruiting on Soviet soil. At age 16, my grandfather enlisted. He then traveled with the army across Central Asia and the Middle East to Italy, where he participated in the Battle of Monte Casino in 1944.

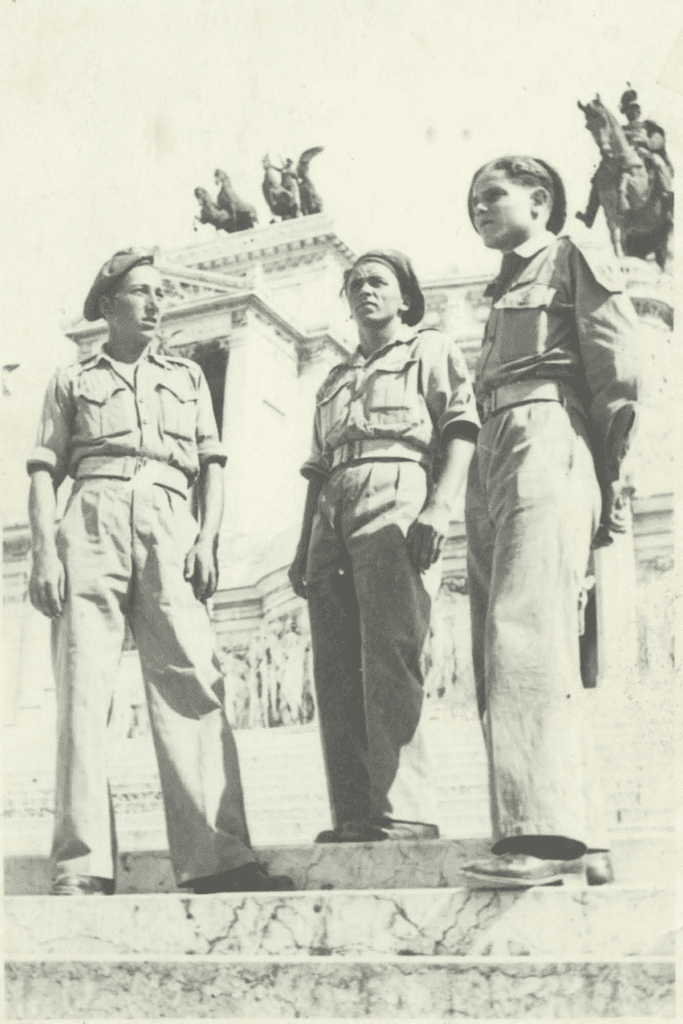

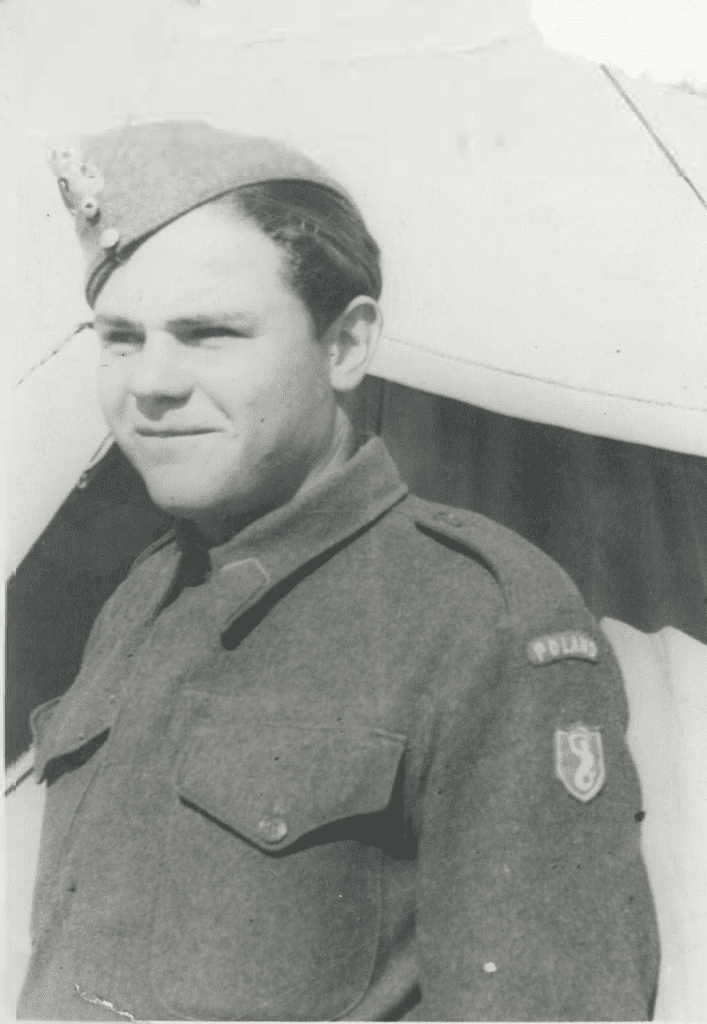

The photograph above was probably taken shortly thereafter, when Borys was 18 or 19. He’s standing (at right) in front of the Vittoriano, a monument to King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, in Rome. My grandfather is wearing his Polish military uniform – see below for a closer look:

After the war, my grandfather emigrated to Canada. But for the rest of his life, he remained immensely proud of his Polish heritage. He felt a profound connection to history, and more than anything else, he loved to share his story with the people he loved.

Borys Gleb died on Christmas Day, 2021. This photograph is dedicated to his memory and to the history he experienced.

John Gleb is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin and a graduate student fellow at the Clements Center for National Security. John’s research traces the emergence of national security as a concept by documenting attempts to mobilize public opinion on behalf of foreign and defense policy during the early twentieth century.

John thanks his aunt, Cindy Rutschmann, for providing him with copies of the two photos enclosed above.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.