By Neel Baumgartner

Setting aside large tracts of land for preservation and public use was a unique idea in the late nineteenth-century United States as the country focused on westward expansion and development.

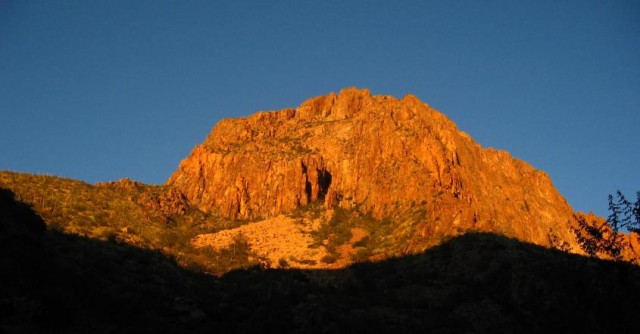

However, rather than moving to protect land untouched by human hands, the creation of the National Park System includes stories of people already using these spaces in a variety of ways. In 1872, the world’s first national park, Yellowstone, was established out of publicly held lands formerly occupied by Native Americans. Seventy-two years later, Big Bend National Park was formed in the Chihuahuan Desert of southwest Texas out of private land parcels acquired by the State of Texas in the early 1940s.

Within the Big Bend region, as with many other national parks, land has moved through a number of successive stages of occupation and ownership. The first wave of dispossessions were predicated on the so-called “inefficient use” of productive lands by local or indigenous groups in favor of miners, ranchers, homesteaders, and speculators. Then, in a peculiar mental shift, the second dispossession was based on reconstituting these same lands as essentially valueless or valuable only as a tourist attraction.

With the absence of federally owned property in Texas due to its unique method of entry into the union, the state took the lead in acquiring land it would ultimately cede to the federal government. In order to turn the area into a national park, the state legislature appropriated $1.5 million. The Texas State Parks Board (the precursor to the current Texas Parks and Wildlife Department) set up the Big Bend Land Department (BBLD) to acquire property for the proposed park. From a small core of state park land along the Chisos Mountains and the canyons of Santa Elena, Mariscal, and Boquillas, the BBLD accumulated almost 700,000 acres from surrounding private property, school fund land, and unallocated state lands belonging to the General Land Office. Notably, in its correspondence with landowners, the BBLD claimed that Big Bend was “fit for nothing excepting park purposes and that is why it was selected.” Beyond the small number of ranchers and miners actually living on the land there, hundreds of non-resident owners had purchased land sight unseen as part of a variety of oil and mineral speculation schemes.

Katherine Southworth preserved a copy of a letter she received from one such prospector after her purchase of approximately twenty-six acres for $518.40 in 1921. The Columbia Sales Company’s banner proclaimed, “when you buy fee oil lands you don’t lose.” The letter congratulated her on her purchase and reassured her that the land was valuable: “We feel that we can say to you that you have used good judgment and have made a good investment. The many eminent Geologists who have reported this territory as promising for the next great oil field will cause millions of dollars to be spent in development work in this locality as soon as financial conditions improve. Some of this development work will be near your property, which will mean much to you as well as ourselves. You have an opportunity of becoming independent from this investment, – this is the only safe way to make an investment in oil; the only way to make large returns from a small investment and, at the same time, know that your money is safe in land.” But Southworth’s property was appraised by the BBLD at only $26.

In a letter to another land owner, M.C. and A.C. Donahoe of Missouri (reprinted below), the BBLD sympathized with their predicament, but blamed the buyers, explaining, “Texas is an extremely large state, as you know, and you picked the one small spot in the Chisos Mountains in Brewster County, Texas, to make your investment in land that is fit for nothing unless the Federal Government can turn it into some sort of scenic beauty.” Unfortunately, for Southworth, the Donahoes and many others, their investments would not return any personal dividends. With the predominantly arid condition of the areas to be included within the park as well as the harsh economic environment of the Great Depression, the state was able to purchase land at an average price of only one to two dollars per acre, much less than most owners believed it was worth.

Taking a break from reading progress reports on the Normandy invasion, President Franklin Roosevelt accepted the deed for the new park from a delegation of Texans on June 6, 1944. After this official transfer of BBLD lands to the federal government, the park was formally opened to visitors shortly after the close of World War II. Big Bend National Park, assembled from a patchwork of private parcels, was left to the National Park Service in order to recast the region’s deserts, canyons, and mountains as “some sort of scenic beauty.”

Letter from J.C. Epperson to M.C. and A.C. Donahoe:

June 20, 1942

M.C. and A.C. Donahoe

5829 Nina Place

St. Louis, Missouri

Gentlemen:

Your letter of the 15th addressed to our Mr. James Moore has been turned over to me for reply, because Mr. Moore joined the Navy a few days ago.

I have reviewed the files and found that you did not accept the offer of the Texas State Parks Board submitted by our Mr. Bob Hamilton, consequently there was no occasion for Mr. Moore corresponding with you after he filed the condemnation suit. He did send answers to persons owning land in Survey 77, Block C-9 who had accepted our offers and wrote them at the same time. If you had accepted our offer you would have received a similar letter and answer to be filed by you.

We realize that professional promoters from other states years ago concluded that they would have a gold mine if they could acquire some of the cheapest land in the State of Texas and sell it out to people residing in other states at fabulous prices when compared with the real value. You unfortunately became one of their victims. Texas is an extremely large state, as you know, and you picked the one small spot in the Chisos Mountains in Brewster County, Texas, to make your investment in land that is fit for nothing unless the Federal Government can turn it into some sort of scenic beauty. I note in the next to last paragraph in your letter you state that you are from Missouri. It has always been my understanding that the expression being “from Missouri” meant that the person making the statement had to be shown. The time for you to have been from Missouri was when the promoter sold you this land at many times its actual value.

The Texas State Parks Board does sincerely regret that any person anywhere was so over reached when he bought land in this area, but they cannot pay more than the reasonable cash market value on the land. If you have any doubts about the reasonable cash market value of the land, anybody in this county ought to be able to enlighten you, and if you will make such investigation I am sure you will be convinced that we did, in fact, offer you all or more than the land is worth, and, instead of blaming our Board or anybody else in Texas, you will place the blame for your bad investment where it rightfully belongs. We are condemning this whole section 77 in Block C-9, and we are going to insist that no more than the actual cash market value of the land is awarded. That sum can not be possibly more than $1.50 per acre and it should be less. Those of the owners who accepted our offer will receive the amount we offered them net. The others will not.

Yours very truly

Texas State Parks Board

Sources: J.C. Epperson to M.C. and A.C. Donahoe, 20 June 1942, Box 2005/041-27, Big Bend Collection, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Columbia Sales Company to Katherine Southworth, 12 March 1921, Box 2005/041-26, Big Bend Collection, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

For more on Big Bend and its beginnings:

Patricia Wilson Clothier, Beneath the Window: Early Ranch Life in the Big Bend Country.

John R. Jameson, The Story of Big Bend National Park.

J. O. Langford with Fred Gipson, Big Bend: A Homesteader’s Story.

James W. Steely, Parks for Texas: Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal.

Big Bend Photos: J Neuberger

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.