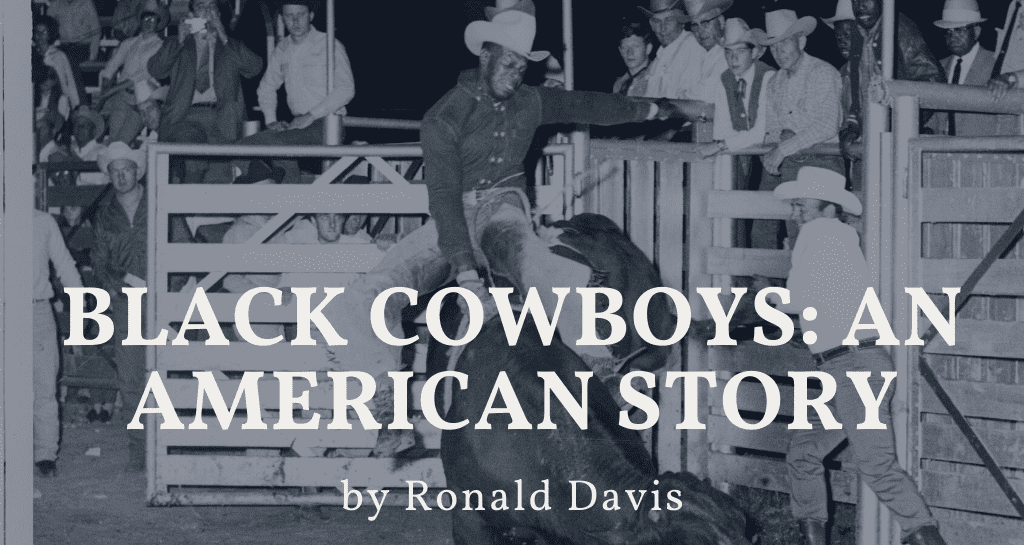

By Ronald Davis

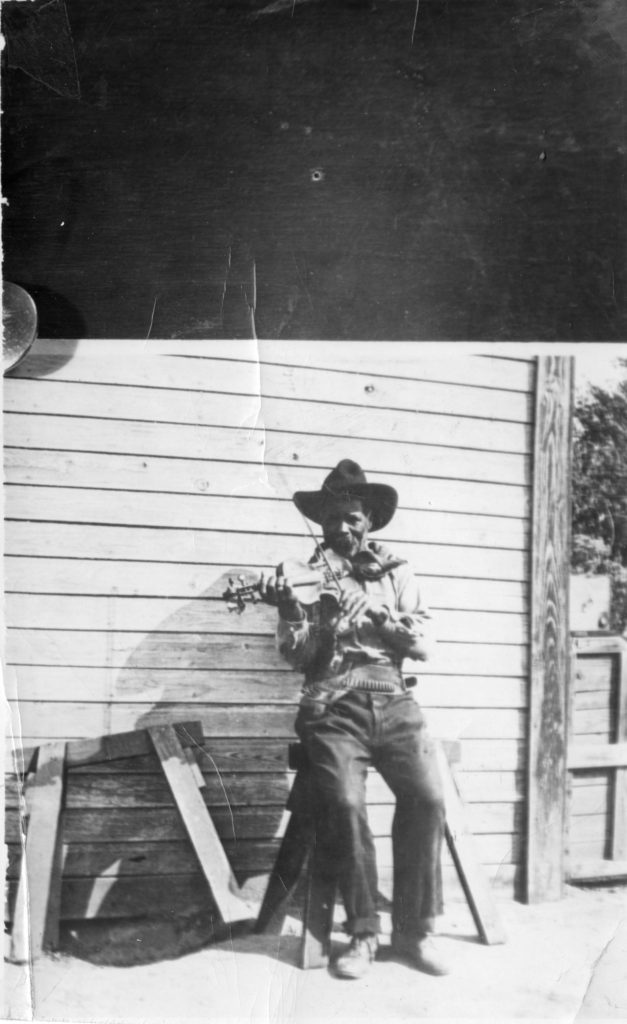

In 1921, while reflecting on the height of the cattle drive era, between 1865 and 1895, then President of the “Old Time Trail Drivers’ Association” of Texas, George W. Saunders, estimated that “fully 35,000 men went up the trail with herds . . . about one-third were negroes and Mexicans.”[1] Eminent historians of African Americans in the West such as Kenneth Porter argue that, “twenty five percent” of all cowboys who participated in cattle drives out of Texas were Black.[2] Yet, this is just the beginning. Some Black cowhands never journeyed to Kansas, driving herds of 2000 to 5000 cattle. Some of these women and men, stayed to work on ranches throughout Texas rather than “go up the trail.” They were cooks, and cowboys, horse breakers and trainers. There was more to being a cowboy than eating dust and crossing swollen rivers.

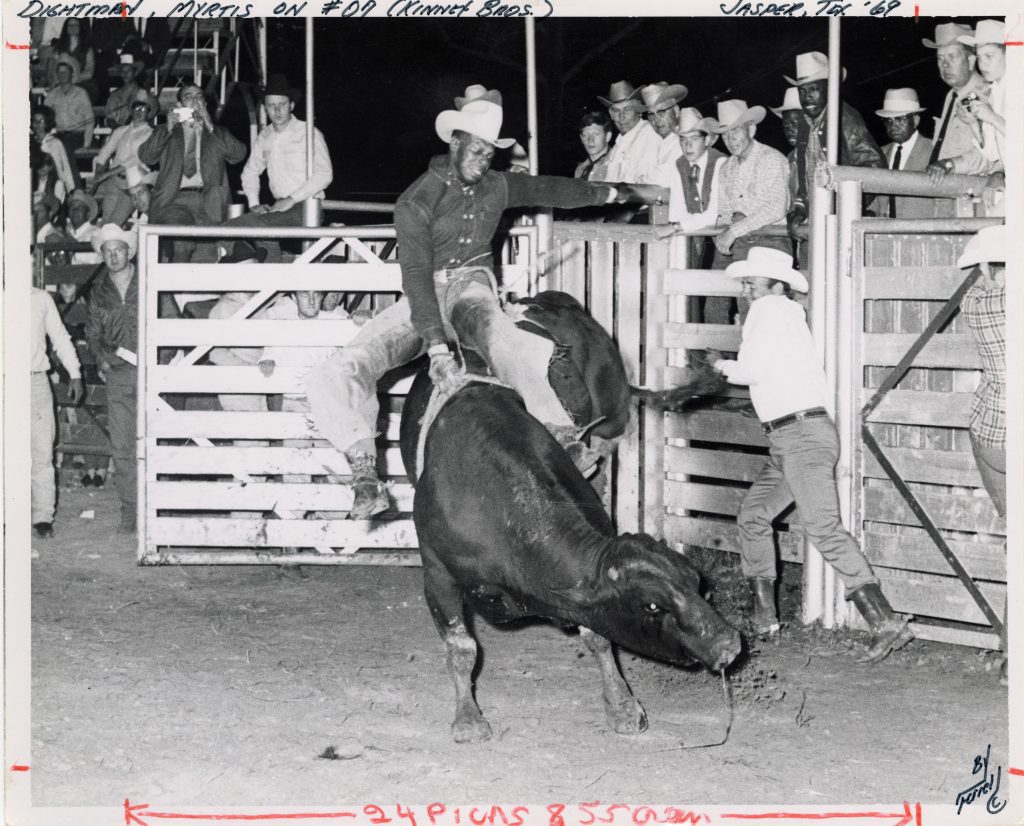

In our exhibit Black Cowboys: An American Story, visitors from Texas, and beyond will be introduced to a diverse group of African American cowhands, from Johana July, a free Black Seminole born in 1860 to Myrtis Dightman, called “The Jackie Robinson of Rodeo” who broke the color line at professional rodeos in the late 1960s.[3] In addition to presenting the public with depictions of numerous Black cowboys, enslaved and free, the Witte Museum introduces the audience to the legacy of Black ranches and freedom colonies throughout Texas. The audience learns about several Black owned ranches that have stood the test of time, outlasting white supremacy and Jim Crow. These ranching families, who continue to ranch the land purchased and maintained by their ancestors in the nineteenth-century, display a tenacity of will and a commitment to their family traditions. They often withstood destruction of their family legacy by organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan while also weathering continual threats of encroachment from neighbors and state governments.

The exhibit investigates the lived experiences of African American cowhands using their own words. Black Cowboys presents to the audience the childhood experiences of the enslaved on plantations and ranches. James Cape, while being interviewed by the Works Progress Administration, remembered that “[w]hen I’s old ‘nough to set on de hoos, dey larned me to ride, tendin’ horses.”[4] Hector Bazy, who wrote an unpublished manuscript detailing his life as an enslaved child and then Black cowboy states, “I had to work on the plantation from the time I was able to crawl.”[5]

Black Cowboys: An American Experience tells the story of over 30 black cowgirls and boys as well as ranchers and cattlemen, many of whom, the people of Texas and the United State have never heard of. Black cowboy and camp cook Jim Perry explains his inability to receive a promotion on the three million-acre XIT Ranch near Dalhart, Texas. After working for the ranch off and on for over twenty years Perry explains, “If it weren’t for my damned old black face I’d have been boss of one of these divisions long ago.”[6] Contemporaries of Perry described him as one of the two best cooks to ever work on the XIT ranch and argued that he deserved the promotion to foreman, yet racism limited his opportunities for advancement. The exhibit also highlights the Wilcox Ranch in Guadalupe County. Stewarded by the grandchildren of Ella Jay Wilcox-Moore, the ranch has remained in the family since 1870. The patriarch of the family, Henry Wilcox, walked from the middle of Seguin, Texas to the Freedmen’s Settlement, Jakes Colony and purchased land once thought undesirable by white Texans. Wilcox became a cattleman and master distiller, his son, Thomas Wilcox, followed suit.[7]

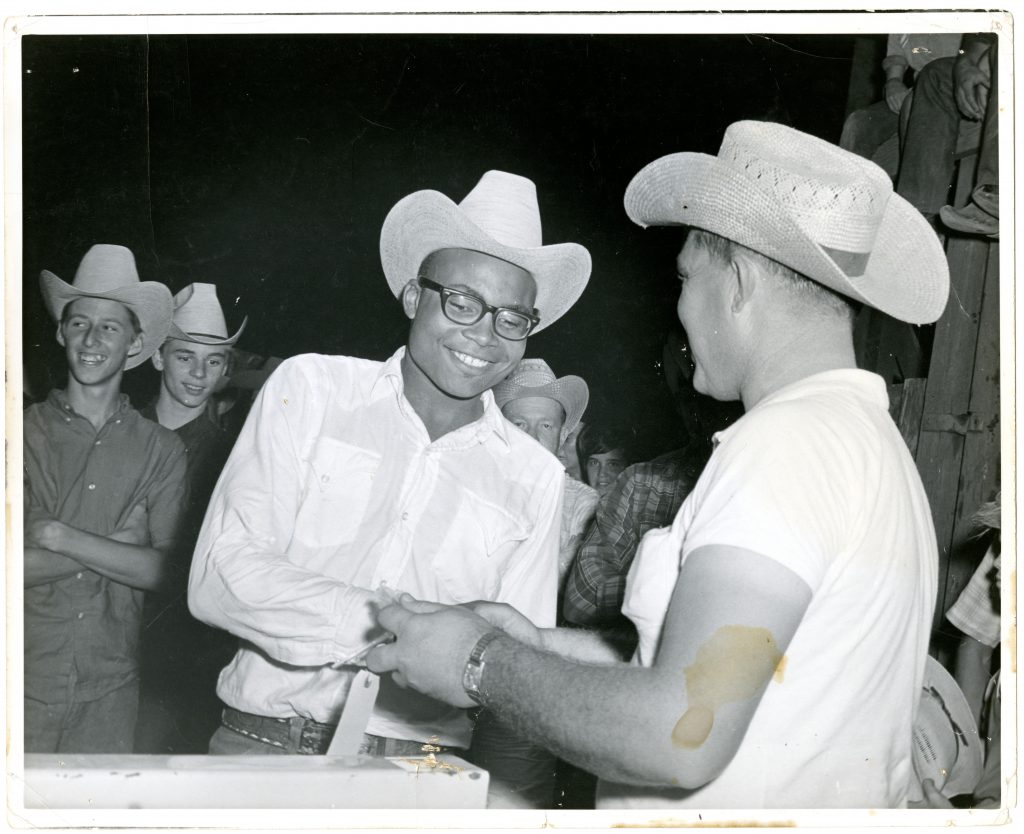

Rounding out Black Cowboys are current cowboys and rodeo champions from Tex Williams, the first African American to compete and win the Texas State High School Finals rodeo in 1967 for Bareback Riding and Myrtis Dightman, who rodeo professionals credit with breaking the color line in Professional Rodeos in the late 1960s.[8] These rodeo performers achieved championships and greatness (with many eventually inducted into the ProRodeo Hall of Fame and the National Cowboy Hall of Fame) despite unfair treatment and discrimination.

Next time you are in San Antonio visit The Witte Museum’s Black Cowboys: An American Story, it will be on display until April 2022.

For more information and hours, visit www.wittemuseum.org

[1] George W. Saunders, “Reflections of the Trail,” in The Trail Drivers of Texas: Interesting Sketches of Early Cowboys and Their Experiences on the Range and on the Trail during the Days That Tried Men’s Souls: True Narratives Related by Real Cow-Punchers and Men Who Fathered the Cattle Industry in Texas, ed. J. Marvin Hunter (San Antonio: Jackson Printing Company, 1920), 412.

[2] Kenneth W. Porter, “Negro Labor in the Western Cattle Industry, 1866-1900,” Labor History 10, no. 3 (1969): 347.

[3] Florence Angermiller, Johnanna July-Indian Woman Horsebreaker: a machine readable transcription, Texas, Manuscript/Mixed Material, https://www.loc.gov/item/wpalh002207/ and Christian Wallace, “The Jackie Robinson of Rodeo,” Texas Monthly, 2018, July edition, https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/black-cowboy-the-jackie-robinson-of-rodeo/.

[4] Sheldon F Gauthier, “James Cape,” in Slave Narratives, 2nd ed., vol. XVI (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1941), 193–96.

[5] Hector Bazy, Hector Bazy manuscript, 1910, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian (unpublished, 1910), 3. He is portrayed by actor Eugene Lee in the exhibit.

[6] Cordia Sloan Duke and Joe B. Frantz, 6,000 Miles of Fence: Life on the XIT Ranch of Texas, The M.K. Brown Range Life Series (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1961), 172.

[7] Lola Wilcox-Moore of Wilcox & Moore Legacy Restoration Project, interview, October 15, 2021.

[8] Dightman was not the first black rodeo performer. The history of the rodeo began with small competitions between ranches in the late nineteenth-century. It evolved into a profession during the twentieth-century although Jim Crow created numerous barriers to Black participation. Sometimes this meant exclusion from competition entirely, to unfair judging and results, or unusual requests, such as forcing Black riders to compete in empty arenas before or after the rodeo. For more information of Black participation in rodeos throughout the U.S., the creation of a segregated rodeo circuit and those who insisted on competing during the Jim Crow era see Christian Wallace, “The Jackie Robinson of Rodeo,” Texas Monthly, 2018, July edition, https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/black-cowboy-the-jackie-robinson-of-rodeo/, Elyssa Ford, Rodeo as Refuge, Rodeo as Rebellion: Gender, Race, and Identity in the American Rodeo (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2020) and Demetrius W. Pearson, Black Rodeos in the Texas Gulf Coast Region: Charcoal in the Ashes (New York: Lexington Books).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.