Democratic governments often have a hard time changing their minds, as recent U.S. decision-making about Iraq and Afghanistan has made clear. Even when the United States encountered monumental frustrations and setbacks, Washington kept fighting, adjusting its strategy and tactics but not its overall goals or the assumptions that underpinned them. To withdraw from either country before achieving stated U.S. objectives would, the Bush and Obama administrations agreed, expose the United States to national-security risks. Both administrations surely also feared the domestic political consequences of failing to achieving U.S. goals after thousands of Americans had already died in the effort.

So it was more than forty years ago, when U.S. officials responded to setbacks in Vietnam not by rethinking their goals or assumptions but by affirming their commitment to the war and, for a time, increasing the number of U.S. troops. Indeed, the vast documentary record of the Vietnam War makes abundantly clear that American leaders rarely revisited the fundamental assumptions that guided their decisions to escalate U.S. involvement.

So it was more than forty years ago, when U.S. officials responded to setbacks in Vietnam not by rethinking their goals or assumptions but by affirming their commitment to the war and, for a time, increasing the number of U.S. troops. Indeed, the vast documentary record of the Vietnam War makes abundantly clear that American leaders rarely revisited the fundamental assumptions that guided their decisions to escalate U.S. involvement.

A rare exception was an extraordinary study written by the Central Intelligence Agency in September 1967. By that time, the United States had encountered virtually all of the problems that would eventually doom its war effort in Vietnam. While Lyndon Johnson and his top advisers remained adamant that the United States would suffer intolerable geostrategic reverses if it failed to press on to victory, the CIA report suggested otherwise.

Nations would not fall to communism like a row of dominos if the North Vietnamese won, it insisted. The U.S. reputation for anticommunist resolve would not be forever destroyed. And the Soviets and Chinese would not go on an anti-U.S. rampage around the globe. In short, the study insisted, “such risks are probably more limited and controllable than most previous argument has indicated.”

Nations would not fall to communism like a row of dominos if the North Vietnamese won, it insisted. The U.S. reputation for anticommunist resolve would not be forever destroyed. And the Soviets and Chinese would not go on an anti-U.S. rampage around the globe. In short, the study insisted, “such risks are probably more limited and controllable than most previous argument has indicated.”

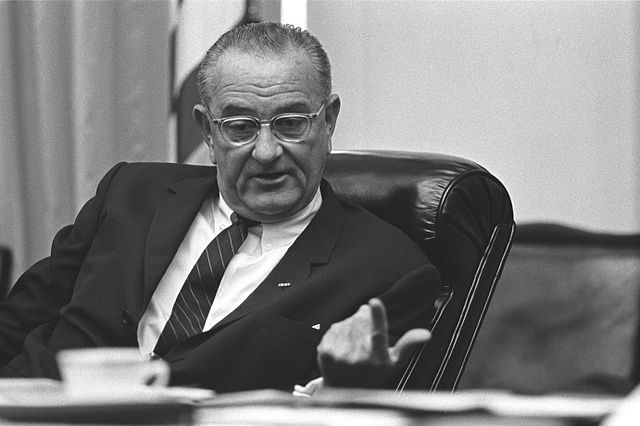

It is hardly surprising that President Johnson ignored the CIA’s position and continued to escalate the war. The study, while extraordinary, was just a drop in the ocean of memos and reports that passed through the Oval Office, many of them suggesting that U.S. objectives were still obtainable. And the prospect of winding down the U.S. commitment was no doubt deeply distasteful to a president who had invested a huge amount of his personal and political capital in waging war in Vietnam. Yet the document stands out nevertheless for the clarity and prescience with which it saw beyond preoccupations of the moment and questioned the conventional wisdom that had led the United States to make a gigantic commitment to a small, distant, and impoverished land. It reminds us, at a minimum, of the value of taking the long view and asking whether the expenditure of resources corresponds to U.S. interests broadly conceived.

It is hardly surprising that President Johnson ignored the CIA’s position and continued to escalate the war. The study, while extraordinary, was just a drop in the ocean of memos and reports that passed through the Oval Office, many of them suggesting that U.S. objectives were still obtainable. And the prospect of winding down the U.S. commitment was no doubt deeply distasteful to a president who had invested a huge amount of his personal and political capital in waging war in Vietnam. Yet the document stands out nevertheless for the clarity and prescience with which it saw beyond preoccupations of the moment and questioned the conventional wisdom that had led the United States to make a gigantic commitment to a small, distant, and impoverished land. It reminds us, at a minimum, of the value of taking the long view and asking whether the expenditure of resources corresponds to U.S. interests broadly conceived.

Read the original study: “Implications of an Unfavorable Outcome in Vietnam,” dated September 11, 1967

Related Reading:

Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War: A Concise International History (2010)

Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and Escalation of War in Vietnam (2001)

Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: A History of the CIA (2008)

A longer version of this essay: “The Consequences of Defeat in Vietnam”

Photo Credits:

Paddler: A US. Medic paddles a three-man assault boat down a canal during Operation Tong Thang (1968). By Department of Defense. Department of the Army. Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations. U.S. Army Audiovisual Center. (ca. 1974 – 05/15/1984) (U.S. National Archives, ARC Identifier 530622) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

LBJ: By Yoichi R. Okamoto [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Gunner: A U.S. Navy river patrol boat crewman maintains vigilance at the .50-caliber machine gun during the boat’s day-long patrol on the Go Cong River (1967). By R.D. Moeser, JOC, U.S. Navy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons