In July 1997, a Cuban-Argentine forensic team unearthed the skeletal remains of Comandante Ernesto “Che” Guevara in Vallegrande, Bolivia. Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, Jon Lee Anderson had gathered new intelligence that led directly to the location of Guevara’s body. The forensic experts immediately distinguished Guevara’s remains from the others. After his death, Che’s executioners had amputated his hands, placed them in a jar of formaldehyde, and sent them to Fidel Castro. Following exhumation, the fallen guerrillas’ remains were placed in coffins and flown to Cuba. That summer, Che Guevara had finally returned to his adoptive homeland.

Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, Jon Lee Anderson had gathered new intelligence that led directly to the location of Guevara’s body. The forensic experts immediately distinguished Guevara’s remains from the others. After his death, Che’s executioners had amputated his hands, placed them in a jar of formaldehyde, and sent them to Fidel Castro. Following exhumation, the fallen guerrillas’ remains were placed in coffins and flown to Cuba. That summer, Che Guevara had finally returned to his adoptive homeland.

Fifteen years after its publication, A Revolutionary Life remains the definitive work on Che Guevara, the dashing Argentine rebel whose “epic dream was to end poverty and injustice in Latin America and the developing world through armed revolution.” Jon Lee Anderson traces Che’s extraordinary life, from his comfortable upbringing in Argentina to the battlefields of the Cuban Revolution; from the halls of power in Castro’s government to his failed campaign in the Congo, and assassination in the Bolivian jungle. Unlike past biographers of Che, Anderson gained unprecedented access to personal archives maintained by Che’s widow, as well as Cuban government documents long kept secret during the Cold War. He conducts extensive interviews with Che’s comrades and enemies, including Felíx Rodriguez, the mercurial Cuban-American CIA operative and Bay of Pigs veteran who ordered Che’s execution.

Anderson paints the portrait of an idealistic, ambitious, and complex man whose unshakable committment was made even more powerful by his unusual combination of romantic passion and coldly analytic thought. He recalls Ernesto Guevara’s epic motorcycle journey through South America as a medical student while underscoring how U.S. intervention in Latin America crystallized Ernesto’s revolutionary consciousness. In June 1954, Ernesto sojourned as a physician in Guatemala, providing free medical care to the poor in the countryside. When a CIA coup overthrew the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz, he sought refuge in the Argentinean Embassy. That summer, Guevara became convinced that only armed revolution could secure the future of oppressed and marginalized Latin Americans everywhere.

Anderson revisits Guevara’s diaries to recapture his first meeting with Fidel Castro in Mexico City. Seeking to recruit new volunteers for a revolutionary war against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship in Cuba, Castro took an immediate liking to the zealous doctor from Argentina who longed to prove his revolutionary credentials. In November 1956, Guevara, Fidel Castro, his younger brother Raul, and eighty volunteers set sail for Cuba, launching a guerrilla war in the Sierra Maestra mountains that would oust Batista on New Years Day 1959.

In January 1959, Che personally oversaw the revolution’s consolidation. He implemented the Agrarian Reform Law of 1959, presided over the trials and executions of ex-Batista functionaries, represented Cuba at the United Nations, and commanded revolutionary forces during the Bay of Pigs invasion. By 1965, Che grew tired of his desk job at the Economy Ministry. Anderson argues that the thrill of battle gave Che meaning. He dreamed of exporting the Cuban Revolution to the rest of Latin America and he chose Bolivia to open a new front. However, unlike Cuba, the Bolivian campaign was a disaster from the start. It was also Che’s last. The local Bolivian Communist Party refused to support the Cuban revolutionary effort on their soil. Che’s team also failed to recruit Quechua Indians. In autumn 1967, the guerrillas ran out of weapons, ammunition, and supplies. CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces ambushed Guevara’s troops in Vallegrande. On October 10, 1967, the world woke up to the news that Che Guevara had been killed in the Bolivian jungle.

A Revolutionary Life is a must-read for Latin Americanists, Cold War buffs, and aspiring revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries everywhere. Anderson sheds light upon little known details of Che’s life, including his harsh criticism of the Soviet Union and his ardent support for the emergent “nonaligned” movement in the Third World. Most important, he emphasizes Che’s unyielding commitment to his beliefs. While other Marxist-Leninists exploited their privilege, Che remained a full-time revolutionary. When he wasn’t studying political economy, Che could be found teaching literacy and arithmetic to his young bodyguards or working eighteen-hour days cutting sugar cane as part of his voluntary labor program. He believed firmly in the possibility of a pan-Latin American revolution, a cause for which he readily gave his life.

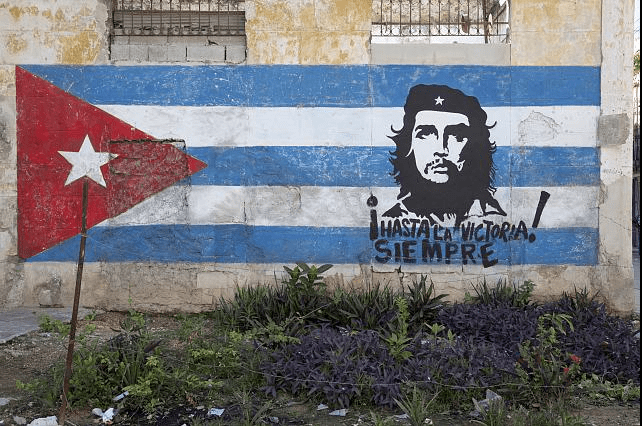

Finally, Anderson’s is a biography that calls into question the dismissal of revolutionary socialism and alternative paths to development in Latin America. Today, leftists in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina breathe life into Che’s pan-Latin American vision, rejecting orthodox neoliberalism in favor of state-sponsored development and regional integration. They threaten to boycott the upcoming Organization of American States (OAS) summit in Cartagena, Colombia, if the United States continues to prevent Cuba from participating. Meanwhile, Bolivian President Evo Morales recently ordered the armed forces to adopt Che’s famous salutation, “hasta la victoria siempre” or “forever onward toward victory,” as its official slogan. Ironically, the very institution that killed Che Guevara forty-five years ago now immortalizes his legacy. In 2012, Che still lives.

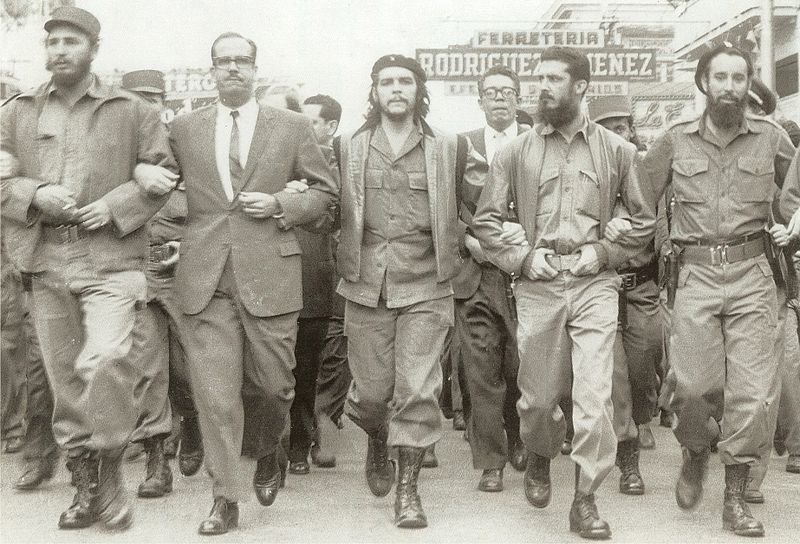

Photo credits:

“Memorial service march for victims of the La Coubre explosion,” 5 March 1960

Museo Che Guevara via Wikimedia Commons

Carol M. Highsmith, “Hand painted mural showing the Cuban flag and Che Guevara, neighborhood in Old Havana, Cuba,” 11 January 2010

Photographer’s own via The Library of Congress

You may also like:

Takkara Brunson’s “Making History” podcast, where she talks to us about her research in Cuba and her dissertation on gender and social identity in pre-revolutionary Cuba.

Aragon Storm Miller’s review of “Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Missile Crisis.”

Yana Skorobogatov’s review of “Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976”