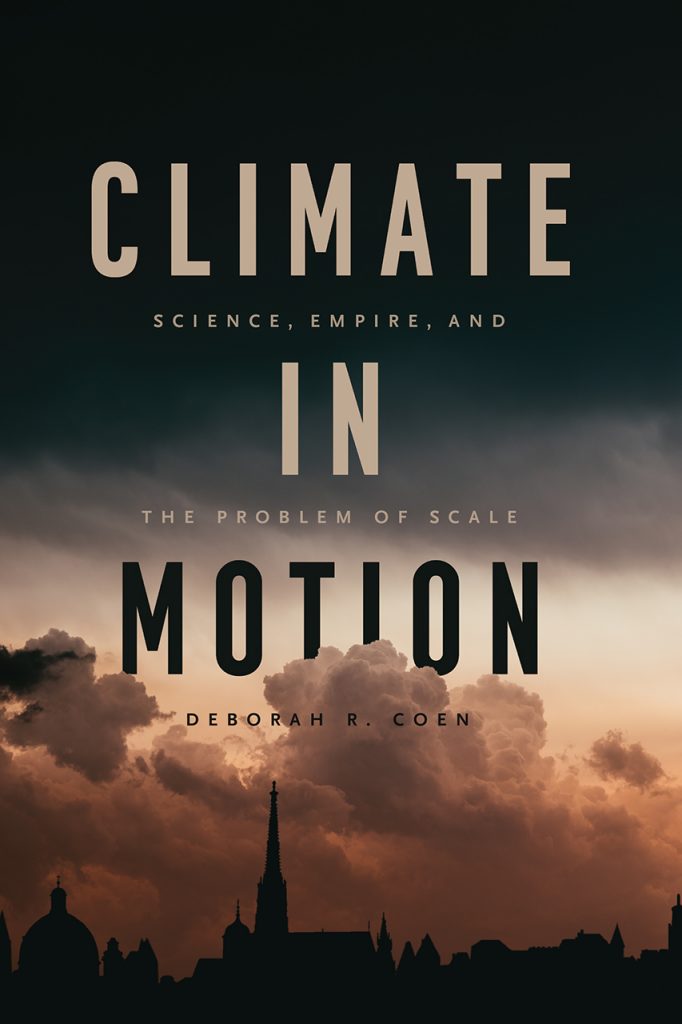

Climate science communication suffers from a problem of scale: how to accurately describe superhuman events without swallowing up local variations and human agency in the process. Climate in Motion offers a fascinating historical account of how scientists in the Austro-Hungarian Empire held local and global climate phenomenon in a productive tension. In so doing, it provides insights into translating massive systems into scales humans can more readily make sense of. Deborah Coen examines the Empire’s embrace of dynamic climatology — a phenomenon where scholars applied the physics of heat and fluid motion to make sense of the climate. This book is divided into three parts—all connected with the central theme of interweaving the global and local to grasp climate events.

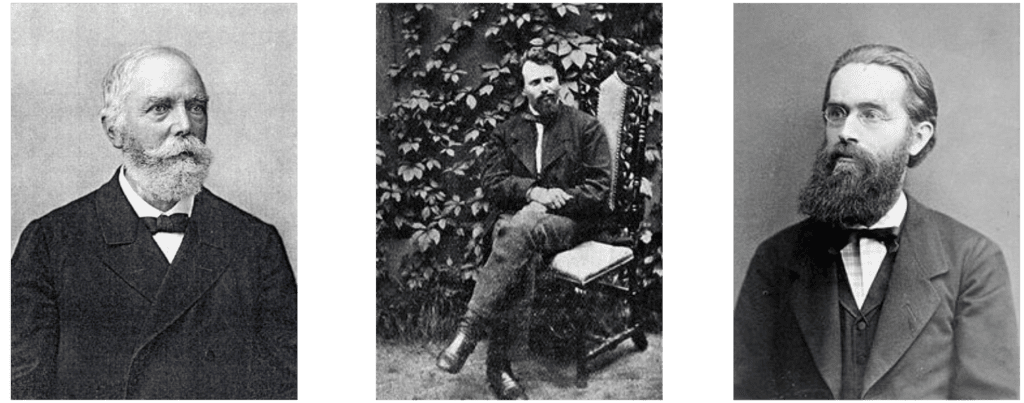

The first section examines the relationship of the Austrian state to scientific discovery generally and climate in particular. State-sponsored scientists like Anton Kerner, Emanuel Purkyně or Julius Hann dedicated themselves to the study of local perspectives as field scientists, synthesizing their work into a combined whole. As “civil servants,” their work joined with early collectors of species to exceed the scientific, establishing and justifying the rule of the Habsburg monarchy. For Coen, state-sponsored scientists saw themselves as bridges for the “Austrian problem” of containing various ethnic and culturally divided groups under one unified system. In this sense, the notion of unity-in-diversity as a Habsburg trope was applied to the varied Austrian climate itself.

The second section analyzes shifts in depictions of climate. Scientists translated abstract climate processes to the public by generating new climate maps, models of winds and cyclones as well as literary works that connected local experience to climatic systems. The overarching theme emphasized is an emerging sense that the climate is dynamic – connected with and sensitive to changes in local weather (e.g. storms). In contrast, previous models understood climate as static – regionally segregated, stable, and removed from local weather anomalies. This new framework saw contrasting and distinct climate regions as necessary counters in a larger Austrian climatic equilibrium (imagined to be a miniature of the world).

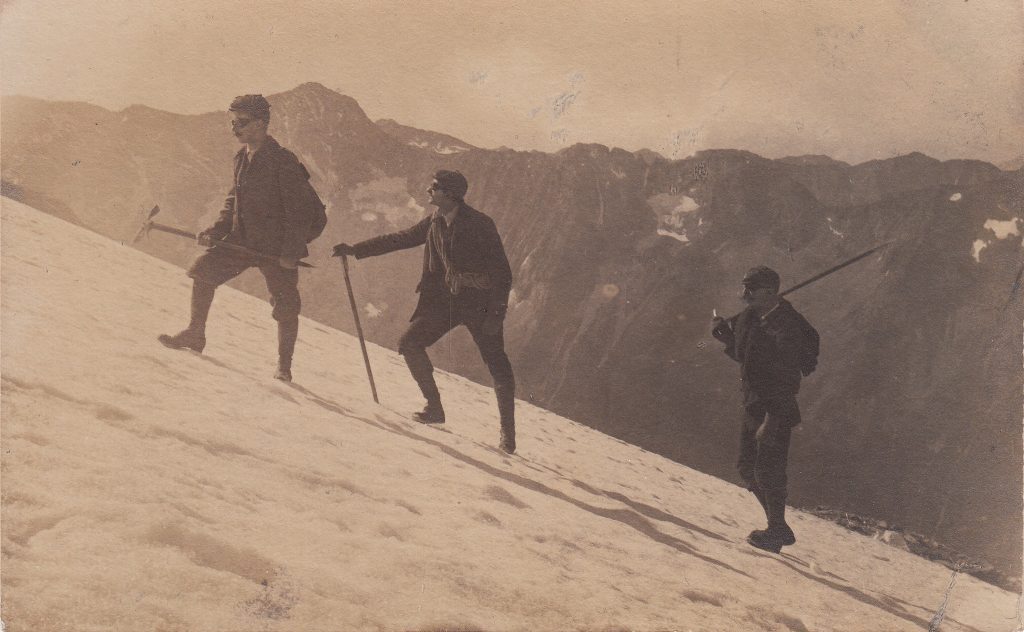

The third section examines “scaling” more explicitly, analyzing debates over deforestation, plants as local tools to map a larger climate history, and personal accounts of climate scientists. Finally, Coen tracks the rise of German-influenced scientific thinking in 1914 that distorted the Hapsburg account of environmental interconnectedness and dynamism in favor of an account that emphasized discrete and regional climates associated with their occupant’s placement on a cultural hierarchy. Coen argues that scaling as a process can re-orient how we represent and perceive the environment. This shifts consideration of environmental processes from either purely abstract or purely localized towards a deeper, more-than-human perspective that was as much emotional, desire-laden, and political as it was strictly scientific. For example, Coen examines autobiographical accounts of scientists that connected their scientific work on climatology with personal self-doubt, longing for home, homoerotic encounters, and an overwhelming sense of the natural sublime. Coen sees “scaling up” as a necessary shift in ethical perspective that recognizes the interconnectedness of humanity and natural forces (as represented in the interplay between climates, local environments, political and cultural divisions etc.) while also “zooming in” to account for seemingly insignificant “small” effects that combine to form that larger connection. In the conclusion, she puts this in tension with the IPCC’s disproportionate focus on the global North as the metric for climate devastation (much as Austrian weather stations pooled in Vienna or the Alps created evidential problems for understanding the climate of other regions).

This strength of this book lies in its rigorous analysis of the intimate connection between governmental problems (“The Austrian Idea” or deforestation legislation) and representations of emerging climate science that Coen connects to the present day. It is also the case that a potential weakness of this book is a light explanation of how scaling up can be applied as a practice to present-day global warming (as opposed to regionally specific deforestation). After finishing Climate in Motion,it is extremely clear that non-cognitive and embodied reactions ought to be considered integral to understanding phenomenon like climate change that appear on a superhuman scale. It is considerably less clear, however, how one might go about this recalibrating process or avoid engendering regressive climate responses. It seems likely that the German science Coen is critical of or modern day climate denial also rely on understanding climate through noncognitive sensations of loss, seductions of the exotic and a desire to return to a past home. Viewed as a whole, Climate in Motion offers a rich and fascinating account of the development of climate science in Austria. Historians of climate, the Austrian Empire or anyone curious about looking into the past to grasp the scale of modern climate change will find a compelling account with much to think about.

David Rooney is a Graduate student in Communication Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.