Few topics in history have produced a larger literature than the origins of the Cold War. Since its onset, historians, rightists or leftists, have hotly debated whether the United States or the Soviet Union initiated the mutual antagonism, culminating in the Korean War. After decades of controversy, the scholarly tensions have now died down, though the issue is far from settled, as most Cold War historians moved on to a myriad of other issues. One may, therefore, well ask: Do we need yet another book about the making of the Cold War? Hajimu Masuda says yes. Contrary to the dominant notion of the Cold War as geopolitical and ideological struggle between the capitalist and communist states, Cold War Crucible depicts it as a social construct that local peoples consciously or unconsciously created from the bottom up. For Masuda, the Cold War was a popular fantasy, not an objective reality.

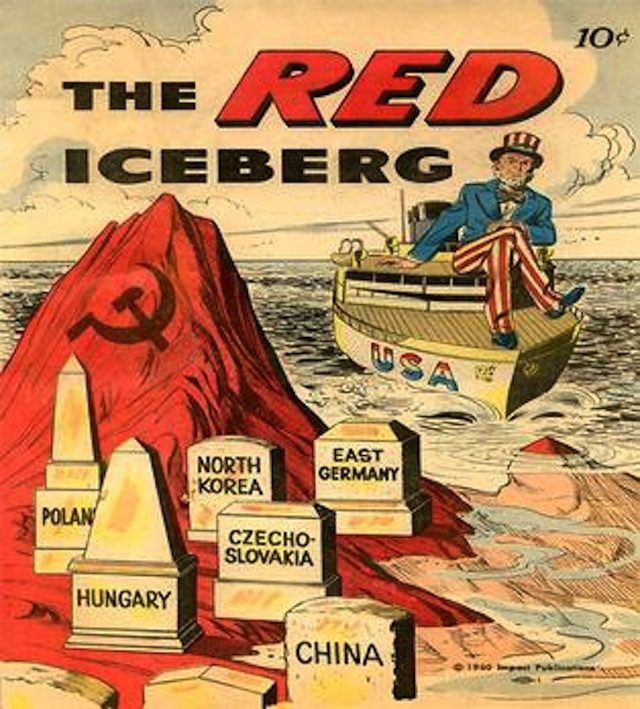

Masuda begins by explaining how Cold War perceptions took shape in the United States, China, and Japan before the Korean War. After WWII, American labor unions, women, and Black people openly called for more rights; Chinese students with vivid memories of WWII opposed U.S. reconstruction of Japan; Japanese workers and students demanded liberal reforms. These social movements, though not caused by communist conspiracies, met a growing backlash from conservatives in each country, who adopted Cold War language, such as “un-American,” “Commies,” and “Reds,” to denounce liberals.

He goes on to analyze how popular discourse distinguishing “us” from “them” during the Korean War consolidated the Cold War realities in the United States and China. Despite deep uncertainty within Harry Truman’s administration about crossing the 38th parallel on the Korean Peninsula, public enthusiasm and Republican pressure for victory against communists emboldened American policymakers. Likewise, despite ambivalence within the Communist Party toward the Korean War, Chairman Mao Zedong decided to send the People’s Volunteer Army because of popular outcry that connected the war against U.S. imperialists to the domestic struggle against landlords and bourgeoisies. Public support for the war, fueled by widespread fear of WWIII, translated local particularities into a monolithic reality of the Cold War.

Worldwide purges of liberals transformed such fears into political realities. In the United States, conservative offensives against African Americans, homosexuals, labor leaders, and immigrants, as well as gender struggle against working women, gave birth to McCarthyism. Similarly, Britain’s crackdown on labor unions, Japan’s Red Purge, Taiwan’s White Terror, and the Philippine’s suppression of “un-Filipino” activists, though all reflecting social divides at the local level, reinforced the Cold War illusion. Masuda concludes that, “the reality of the Cold War materialized in the crucible of the postwar era… leading to the rise of a particular mode of Cold War fantasy that ‘fit’ well with social needs of populations around the world.”

So, was the Cold War simply a fantasy? Of course not. Masuda does not intend to ignore the actual geopolitical and military conflicts in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere. Instead, he argues that the Cold War was a product of complex interactions between international and local leaders and the populace. Although the Korean War was no doubt a military reality for U.S. and Chinese policymakers, ordinary peoples interpreted it through local lenses, which turned the foreign war into a factor in domestic social conflicts. Readers, however, may wonder if Masuda slightly overemphasizes the local agency, as he often cites emotional letters by ordinary citizens, while paying relatively little attention to strategic concerns of top-level policymakers.

Such a caveat aside, Cold War Crucible is a welcome addition to the rich historiography on the origins of the Cold War, as well as the burgeoning literature on the role of popular perception in international relations. Using primary sources from sixty-four archives in ten countries and regions, Masuda offers a truly international history. Although it is clearly too much to ask for more language sources, his research begs further study on Europe and the Soviet Union to examine whether the same reality-making mechanism was in place in the European front of the Cold War, where geopolitical and ideological confrontation was more intense than in Asia.

Hajimu Masuda, Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World (Harvard University Press. 2015)