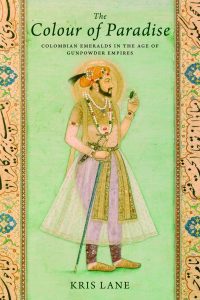

What do an enslaved African miner in colonial Colombia, a Portuguese Jewish merchant in Cartagena, a gem cutter in Amsterdam, and an Ottoman sultan have in common? Kris Lane’s Colour of Paradise ties together the histories of these diverse and geographically distant peoples by tracing the exploitation, trade, and consumption of emeralds between 1540 and the 1790s. In doing so, the author reconstructs the trans-oceanic commodity chains that connected Colombia to various gem markets in Europe. Once in the Old World, Lane demonstrates that emeralds flowed mostly to the Islamic gunpowder empires of Asia such as Mughal India and Safavid Persia. Lane also follows the shifting cultural meanings of emeralds. He emphasizes a concept of economy that includes “all human relationships mediated by material goods.”

What do an enslaved African miner in colonial Colombia, a Portuguese Jewish merchant in Cartagena, a gem cutter in Amsterdam, and an Ottoman sultan have in common? Kris Lane’s Colour of Paradise ties together the histories of these diverse and geographically distant peoples by tracing the exploitation, trade, and consumption of emeralds between 1540 and the 1790s. In doing so, the author reconstructs the trans-oceanic commodity chains that connected Colombia to various gem markets in Europe. Once in the Old World, Lane demonstrates that emeralds flowed mostly to the Islamic gunpowder empires of Asia such as Mughal India and Safavid Persia. Lane also follows the shifting cultural meanings of emeralds. He emphasizes a concept of economy that includes “all human relationships mediated by material goods.”

Lane starts with the uses of emeralds among indigenous populations in pre-Hispanic Colombia. He relies on conquest writings and the work of anthropologists and archaeologists in order to grasp the ritual use and divine connotations of emeralds among the Muisca and other native populations. The Spanish conquest of the territories of the Muzo Indians started an era of uninterrupted mining activity. The original inhabitants of regions around Andean emerald deposits were miners and African slaves. Emeralds were soon incorporated into a small but significant gem market in Spain and its colonies. The stones were frequently found in elite women’s dowries and jewelled religious artifacts. As with other gemstones, emeralds were mostly traded secretly, and the profits were mainly reinvested in enslaved Africans.

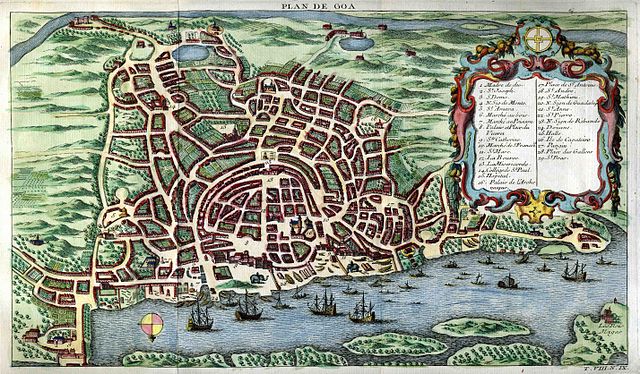

Records of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions and secondary sources about Atlantic merchant communities prove that emeralds moved east across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The fragmentary evidence about the global trade in emeralds describes a “highly uncertain business” carried on along with bulkier commodities such as tobacco and textiles. Sephardic Jewish and New Christian family webs connected Cartagena and Curacao with the emerald trade to India via Seville and Lisbon. These merchants also traded the gems in Portuguese Goa during the Spanish Portuguese union (1599-1616). Many merchants’ last stop was Lisbon where there was a diverse community of diamond polishers, stonecutters, pearl-drillers, and goldsmiths. Some of them became “polyglot globetrotters of uncertain loyalty” who deeply infiltrated the kingdoms of south and southwestern Asia. This diaspora of gem traders active in Asia, Lane argues, became “key vectors in emerald’s steady eastern flow.”

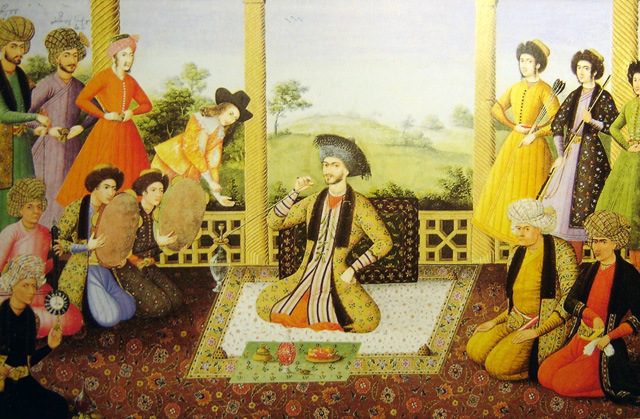

For a historian trained as a Latin Americanist, the task of reconstructing the emerald consumption in South Asia and the Middle East entails a great challenge. Lane used published sources translated from Persian into Spanish, French, Portuguese, and English, in addition to recent translations of documents on the inner workings of the Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman courts. Emeralds became central to the gift economies of Asia. Muslim rulers appreciated the jewel’s opulence as symbol of power and consumed South American emeralds conspicuously. An emerald-handled dagger from the 1740s, molded on orders of Ottoman Sultan Mahmud I as a gift to Persia’s Nadir Sha, appears in Lane’s visual evidence to illustrate the use of the precious gem as “royal armour.”

Going back to the local context of Muzo, Lane identifies cycles of boom and bust in emerald extraction. By the second half of the seventeenth century, the emeralds of Colombia kept fueling contraband trade networks hidden in slave ships and specie cargo. Ships manifests’ and objects recovered from shipwrecks speak of a significant number of Colombian emeralds traveling to Curacao and Jamaica, and to Amsterdam and London. After a decline in production during the early eighteenth century, the Spanish Monarchy sponsored a series of mining missions with European experts to the colonies. The missions in Muzo attempted to increase emerald production but failed to deliver significant improvement. The eighteenth century also saw the extinction of the Safavid Dynasty in Persia and the fall of the Mughal Empire in India, which according to Lane, affected the global emerald trade to an unknown extent.

Unlike the scale and scope of early modern commodity chains of spices, textiles, and precious metals, Lane recognizes that emerald production was not “globally transformative.” Nonetheless, a very special type of commodity chain marked the shifting cultural and political meaning of the gem. An isolated peripheral mining region under Spanish colonialism produced a gem that merchants traded in very small quantities to satisfy the desires of Asian despots. In narrating how the emerald became a global gem, Lane not only sheds light on early modern globalization patterns. Moving from Colombia to Europe, and then to Asia, and back to Colombia, Colour of Paradise devotes careful attention to the communities of miners, merchants, stonecutters, diplomats, kings, and sultans. Lane successfully blends a history of early modern globalization with an unconventional yet refreshing approach to colonial Latin American history.

Colombian emerald mines have been active now for hundreds of years producing the finest gemstones of the world. The extraction of emeralds, however, has been marked by a bloody war among the families that operate the mines and illegal armed actors disputing the control of the so-called “green gold.” Despite this situation, the miners of Muzo dig every day at 590 ft. underground while guaqueros search for the precious stone amid the waste from the mines. On the corner of 7th Street and Jimenez Avenue in downtown Bogota, a number of men stand for hours trading emeralds. Buyers from Japan, Europe, and the United States arrive in the city looking for the gems, and Colombian emeralds continue to fuel global demand for the precious stones.

Kris E. Lane, Colour of Paradise: The Emerald in the Age of Gunpowder Empires (Yale University Press, 2010)

You may also like:

Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

All images via Wikimedia Commons.