For the past few months I have been considering beginning a new digital history research project. I’m not talking about digitizing sets of existing archival documents or starting a new history blog, although those have both proven to be important new tools for researching and talking about history and I will probably have good reason to do both along the way. I’m talking about what I’ve been calling Digital History For Real: a project that creates new kinds of historical documents that can be analyzed with new kinds of computational methods and that can generate new questions or answer old questions with new kinds of historical knowledge. The last part of that sentence is especially important to me. Although Richard White, distinguished historian and digital history pioneer, argued that the production of digital historical documents was itself an analytical project, most of what passes for digital history has been document-making rather than document-reading and document-analysis. This is now beginning to change.

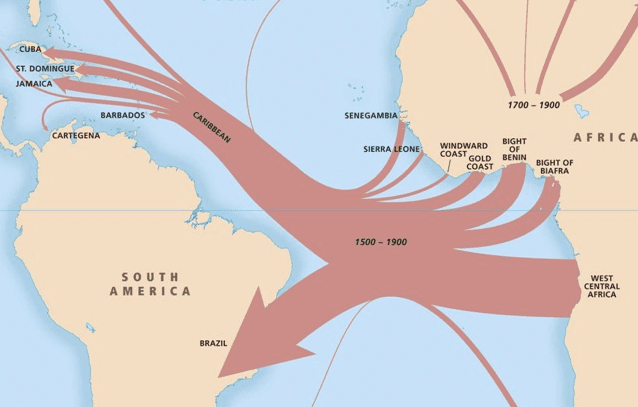

One advantage of digital sources is their scale. For example, we can learn a great deal about the Middle Passage from fine-grained readings of sources about a handful of slave-bearing ships. Now, though, the massive Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database lets historians test our micro-histories and draw new conclusions based on scale. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database exemplifies White’s argument: the compilers of the data had a number of difficult sources to work with and difficult decisions to make about coding entries, a process you can read about in the website’s detailed “Methodology” section. The database has generated a number of stand-alone works as well as providing a source for a whole generation’s histories of the Atlantic. David Eltis, one of the founders, has written a number of award-winning works based on the database, including the Atlas of the Atlantic Slave Trade (co-authored with David Richardson), whose maps have become popular through internet sharing and reporting, including our own article by Henry Wiencek on its maps. Another recent book that uses the TASD is James Walvin’s Crossings: Africa, the Americas, and the Atlantic Slave Trade (2013).

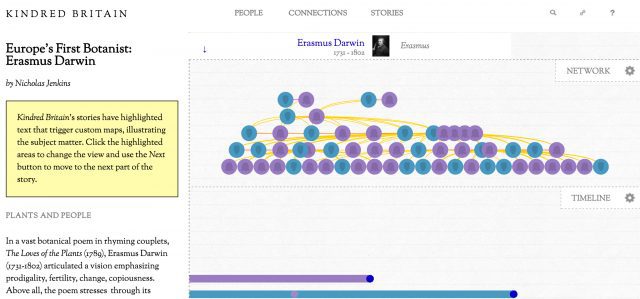

Increasingly, historians are embedding analytical essays and articles into the websites that contain their data and data visualizations. Kindred Britain, a site that shows family links among close to 30,000 people in Britain, includes a section of essays related to the networks the site illustrates. “Britain’s First Botanist: Erasmus Darwin,” — more a blog than a scholarly article — is one of the site’s “Stories” and is accompanied by customized data visualizations (“familial and professional associations” for example) that illustrate its arguments. An older project on networks of Enlightenment literary figures, Mapping the Republic of Letters, a project well funded by prestigious institutions and often held up as a model, illustrates one of the most significant current problems of digital scholarship: sustainability. Mapping promisingly includes a page for listing publications based on its networking data, but the links are all broken at the moment because the team is in the process of re-design. [Update November 4, 2017: This has been partially rectified now. The links are live and one can find more excellent visualizations and other primary sources on the Publications page, but of the six projects listed, only one includes a published article.]

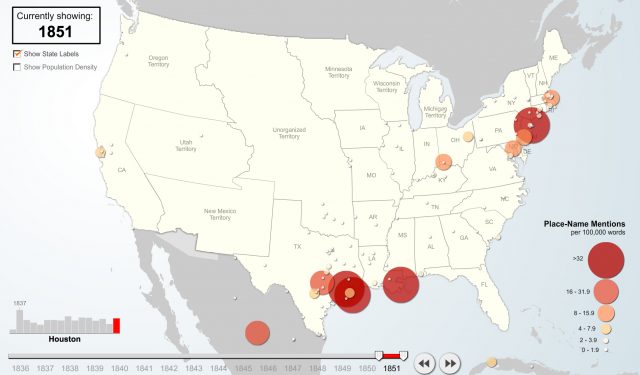

Another approach in digital scholarship is to use computational methods on a smaller scale to address a single problem in some depth. One contribution along these lines is Cameron Blevins’ article in the Journal of American History, “Space, Nation, and the Triumph of Region: A View of the World from Houston.” The article is based on the use of text processing to track place-names in two Houston newspapers for the periods 1836-51 and 1894-1901. A blog on Stanford’s Spatial History website explains the methodology used to quantify the place-name data and the article then analyzes the significance of the patterns the data generated for understanding the historical construction of space through analysis of economic, political, international, and regional contexts.

The sample of projects I’ve been discussing here uses a variety of different computational methods and a variety of written presentations, from blog to scholarly journal article to wide-ranging book, but they are still a rarity among historians. Where the literary studies wing of the digital humanities has developed formal institutional structures like national and international journals and conferences, historians are still more engaged in digitizing data or constructing visualizations of data, or in using digital documents for pedagogy, than in scholarly analysis and institution building. Unlike literary studies, historians are not usually working with ready made texts like novels or poems, but rather have to construct new digital documents before they can get started. And the start-up costs in time and labor and career-risk are high. It remains to be seen how many historians will do more than make digital illustrations for conventional research they carry out with conventional documents. Another problem is that in many departments, digital history remains marginalized or under-developed.

My own project is relatively modest in scope. As a historian of Soviet film, I have long been focused on the work of one of film’s great innovators, Sergei Eisenstein. Eisenstein was not only a film director, he wrote the first body of serious film theory and he made thousands of drawings on a wide range of subjects. He was also a key figure in the Soviet film industry and the Soviet culture industry at large. He travelled to Europe, the US, and Mexico between 1929 and 1932 and made contacts in cultural spheres everywhere he went. In other words, Eisenstein was at the center of a number of important, overlapping social and political networks. When I stumbled on the networking website, Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, one of the best known examples of social network analysis in the humanities and devoted to the social networks in which Bacon travelled, I thought it would be fun to plot the networks revolving around Eisenstein and his many acquaintances. He knew everybody, but how were his contacts connected? I am especially interested in the ways personal relationships got movies made in the Soviet Union. Patronage seems to have played a significant role in all the highly politicized arts communities there and I wondered if I could track patronage relationships to understand its role more thoroughly.

On the set of Ivan the Terrible (L-R) Mikhail Romm as Elizabeth I in drag, Eisenstein, and Andrei Moskvin, Director of Photography. Photograph by V. V. Dombrovskii

In other words, I have a lot of questions about Eisenstein and the Soviet film industry that haven’t been studied, but I don’t know yet if digital social networking computation can help me answer them. For example, I don’t yet know if I want to put Eisenstein at the center of a set of networks or if I want to plot the industry as a whole where Eisenstein would be only one important node. Social networking analysis is very basically a set of nodes and connections. I don’t yet know how to weight or measure the various relationships that one can plot using networking nodes and connections. I also don’t know if the answers are worth the investment of time and labor.

I have been working with a colleague, Seth Bernstein, at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, who has done much of the preliminary work in creating a database of cast and crew members of Soviet films. And this week, I’ll be taking a hands-on seminar in social network analysis offered by the American Historical Association at its annual convention and taught by Jason Heppler. I hope that the workshop will help me decide whether to move forward with the project.

In order for me to decide to go ahead, I have to be convinced that I can do more with the technology than make a new database; I will have to be able to produce data on social relationships in the Soviet film industry that form the basis of a new perspective and new analysis of the subject. I will also have to find out how much of the work I can do myself. Most digital scholarship is collaborative and requires significant funding; I’m hoping to design a project I can do without a huge, expensive team. I also want my project to be fully integrated into the academic fields of history and film scholarship; I’m not interested in a project that is isolated or marginalized on a methodological island. And it will have to be fun.

If I decide to plunge into this new methodology that I’ve only passively observed and consumed until now, I will be using this space to record my progress. I hope you will follow along with me as I explore a world that is sure to be challenging and interesting.

You might also like:

Joan Neuberger, “Public and Digital: Doing History Now.”

Thanks to Jason Heppler, Jim Sidbury, and Steve Mintz for providing some of the sources for this post.

![]()