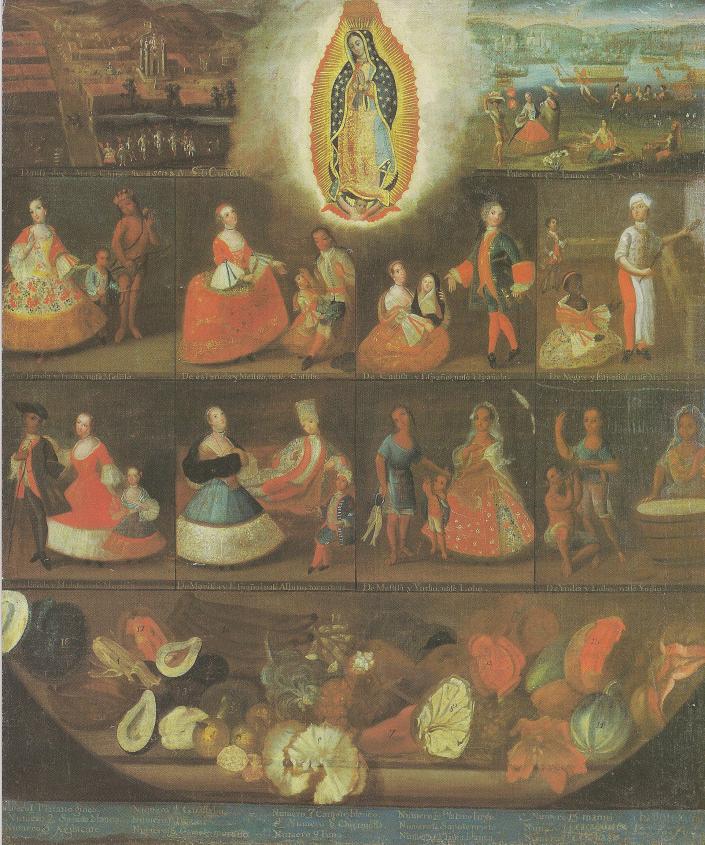

In 1746 Dr. Andrés Arce y Miranda, a creole attorney from Puebla, Mexico, criticized a series of paintings known as the cuadros de castas or casta paintings. Offended by their depictions of racial mixtures of the inhabitants of Spain’s American colonies, Arce y Miranda feared the paintings would send back to Spain the damaging message that creoles, the Mexican-born children of Spanish parents, were of mixed blood. For Arce y Miranda, the paintings would only confirm European assumptions of creole inferiority.

Casta paintings first appeared during the reign of the first Bourbon monarch of Spain, Phillip V (1700-46), and grew in popularity throughout the eighteenth century. They remained in demand until the majority of Spain’s American colonies became independent in 1821. To date over one hundred full or partial series of casta paintings have been documented and more continue to surface at art auctions. Their popularity in the eighteenth century suggests that many of Arce y Miranda’s contemporaries did not share his negative opinions of the paintings.

The casta series represent different racial mixtures that derived from the offspring of unions between Spaniards and Indians–mestizos, Spaniards and Blacks–mulattos, and Blacks and Indians–zambos. Subsequent intermixtures produced a mesmerizing racial taxonomy that included labels such as “no te entiendo,” (“I don’t understand who you are”), an offspring of so many racial mixtures that made ancestry difficult to determine, or “salta atrás” (“a jump backward”) which could denote African ancestry. The overwhelming majority of extant casta series were produced and painted in Mexico. While most of the artists remain anonymous, those who have been identified include some of the most prominent painters in eighteenth-century Mexico including Miguel Cabrera, Juan Rodríguez Juárez, José de Ibarra, José Joaquín Magón, and Francisco Vallejo.

Casta paintings were presented most commonly in a series of sixteen individual canvases or a single canvas divided into sixteen compartments. The series usually depict a man, woman, and child, arranged according to a hierarchies of race and status, the latter increasingly represented by occupation as well as dress by the mid-eighteenth century. The paintings are usually numbered and the racial mixtures identified in inscriptions. Spanish men are often portrayed as men of leisure or professionals, blacks and mulattos as coachmen, Indians as food vendors, and mestizos as tailors, shoemakers, and tobacconists. Mulattas and mestizas are often represented as cooks, spinners, and seamstresses. Despite clear duplications, significant variations occur in casta sets produced throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Whereas some series restrict themselves to representation and specification of racial mixtures, dress styles, and material culture, others are more detailed in their representation of flora and fauna peculiar to the New World (avocadoes, prickly pear, parrots, armadillos, and different types of indigenous peoples). While the majority appear to be in urban settings, several series depict rural landscapes.

What do these exquisitely beguiling images tell us about colonial society and Spanish imperial rule? As with textual evidence, we cannot take them as unmediated and transparent sources. Spanish elites’ anxiety about the breakdown of a clear socio-racial hierarchy in colonial society–the sistema de castas or caste system–that privileged a white, Spanish elite partially accounts for the development of this genre. Countering those anxieties, casta paintings depict colonial social life and mixed-race people in idealized terms. Instead of the beggars, vagrants, and drunks that populated travelers’ accounts and Spanish bureaucratic reports about its colonial populations, viewers gaze upon scenes of prosperity and domesticity, of subjects engaged in productive labor, consumption, and commerce. Familiar tropes of the idle and drunken castas are only occasionally depicted in scenes of domestic conflict. In addition, European desires for exotica and the growing popularity of natural history contributed to the demand for casta paintings. The only extant casta series from Peru was commissioned as a gift specifically for the natural history collection of the Prince of Asturias (the future Charles IV of Spain). And despite Dr. Arce y Miranda’s fears, many contemporaries believed the casta series offered positive images of Mexico and America as well as of Spanish imperial rule. In this regard, the casta paintings tell us as much about Mexico’s and Spain’s aspirations and resources as they do about racial mixing. Many owners of casta paintings were high-ranking colonial bureaucrats, military officials, and clergy, who took their casta paintings back to Spain with them when they completed their service in America. But there is also evidence of patrons from the middling ranks of the colonial bureaucracy. Very fragmentary data on the price of casta paintings suggests that their purchase would not have been restricted to only the very wealthy.

The casta paintings were displayed in official public spaces, such as museums, universities, high ranking officials’ residences and palaces, as well as in unofficial spaces when some private collections would be opened up to limited public viewing. The main public space where casta paintings could have been viewed by a wide audience was the Natural History Museum in Madrid.

Regardless of what patrons and artists may have intended casta paintings to convey, viewers responded to them according to their own points of reference and contexts. While much remains to be learned about who saw sets of casta paintings and where they saw them, fragmentary evidence suggests varied audience responses. The English traveler Richard Phillips, visiting the Natural History Museum in Madrid in 1803, enthusiastically encouraged his readers to go and see the casta paintings as exemplary exotica along with Japanese drums and Canopus pots from Egypt. Another English traveler, Richard Twiss, expressed skepticism about the inscriptions that described the racial mixtures depicted in a casta series he viewed in a private house in Malaga. And, to return to Arce y Miranda in Mexico, the casta paintings for him signified a slur on the reputation of creoles in Mexico.

Although we have a good general understanding of the development of this provocative genre much remains to be understood about the circulation, patronage, and reception of the casta paintings. We know, for example, that some casta series found their way to England. One tantalizing piece of evidence comes from the British landscape painter Thomas Jones (1742-1803) who made a diary entry in 1774 about a set of casta paintings he viewed at a friend’s house in Chesham. How these paintings were acquired by their English owners, as purchases, gifts, or through more nefarious means, remains an open question. We also need to know much more about patrons of the casta paintings and the painters in order to deepen our understanding about innovations and new interpretations that appear in this genre.

This is an electronic version of an article published in the Colonial Latin American Review © 2005 Copyright Taylor & Francis; Colonial Latin American Review is available online at www.tandfonline.com http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10609160500314980

For more on casta paintings:

Magali M. Carrera, Imagining identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings (2003)

María Concepción García Saiz, Las castas mexicanas: un género pictórico americano (1989)

Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (2004)

You may also like: Naming and Picturing New World Nature, by Maria Jose Afanador LLach (here on NEP)

Credits:

1. De Español y Mestizo, Castizo de Miguel Cabrera. Nº. Inv. 00006

2. De Chino Cambujo y India, Loba de Miguel Cabrera. Nº. Inv. 00011

3. Castas de Luis de Mena. Nª.Inv. 00026

Posted by permission of El Museo de América, Madrid