For nearly 30 years, historians have debated about the use of former slave narratives as a “valid” historical source. Scholars question the authenticity of interviews collected in the 1930s, often by white Works Progress Administration (WPA) field workers. Were the interviews honest depictions of the past or blurred historical memories? Did the former slaves feel comfortable answering questions about enslavement? How old were they during slavery? How much were these stories edited? Any study of the recordings must begin by understanding the editors. Their background, beliefs, and views of slavery all influenced the ways they recorded the former slaves’ stories. Fortunately, we have detailed biographical information about the WPA field workers in addition to their notes, instructions, and editorial process. With all this evidence, we can examine slave narratives in a multi-dimensional manner. Comparing drafts of the narratives with field notes and final edited copies, opens a window onto the writing process that one rarely witnesses. Such detailed examination makes it possible to use slave autobiographies as we use plantation records and other sources without privileging one over the other.

In addition to written records of slave narratives, we can now listen to the former bondpeople talk about their experience with the peculiar institution. The Library of Congress has a collection entitled “Voices from the Days of Slavery” which contains nearly seven hours of audio recordings of formally enslaved men and women. These audio files are the original recordings of WPA interviews that were used to compose the written slave narratives. As my students often say, it’s even more chilling to hear former slaves recount their experiences of slavery than to read their autobiographies in an edited collection. The audio files are revealing in that one can hear the questions posed and answered in their original form. Historians can compare the questions asked, place the responses in context, and learn about omitted material. This alone allows the researcher a different lens to explore a somewhat controversial historical source.

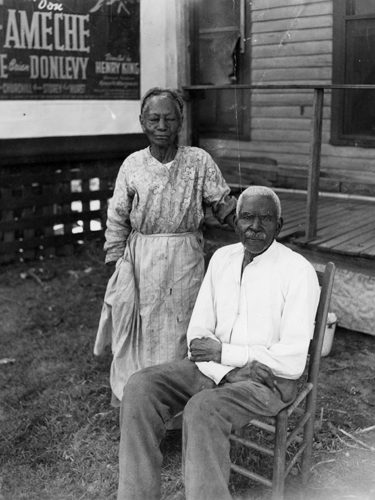

Jack and Rosa Maddox, a formerly enslaved couple from Texas pictured here, shared their experiences with WPA worker Heleise M. Fereman in the late 1930s. Two versions of their narrative, (one seventeen pages, the other seven), and a photograph are available at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas at Austin. This is a rather unusual narrative because it contains an interview of the couple together; one can glean a bit about their interaction with each other as well as with Fereman. Viewing the two documents, there is a stark difference in the language between the long and short version of the narrative. One begins with Jack Maddox stating “Yes I was born a slave and so was Rosa.” The other begins with “Yes’m, I’s borned a slave and so was Rosa.” This distinction serves as one of the primary reasons scholars question the use of enslaved narratives. Which version is correct? In versions of narratives from Virginia, historian John Blassingame discovered references to cruel punishments, forced marriages, family separations, ridicule of whites, and the kindness of Union soldiers that often did not appear in the original WPA interviews. How does one rectify these discrepancies? It is important to view the original source in all of its iterations, in this case, the field notes, instructions to WPA interviews, any drafts of the narrative, as well as the audio tape if available. All of this is necessary to let the enslaved testify.

This narrative was recorded December 2, 1937

JACK and ROSA were both born in slavery, Jack to the Maddox family, in Georgia, and Rosa to the Andrews family in Mississippi. They were married in Union Parish, Louisiana, in 1869, and are proud of the fact that they have been married sixty-nine years and “was a lovin’ pair all dem years.” They live in Dallas, Texas.

Jack begins the story:

“Yas’m, I’s borned a slave and so was Rose. We done git out of slavery and I’s better off for gittin’ out, but Rosa don’t think that-a-way. She says all we is freed for is to starve to death. Her white folks was good to her, that’s the reason she thinks that-a-way. But don’t you ‘spect me to say I loved my white folks. I love ‘em like a dog loves hickory! I can say them things now, and I’d say them anywheres—in he court house, before the jedges, before Gawd—‘cause they done done all to me they can.

“I’s borned in Georgia and my mammy’s name was Lucindy. But she died and left my li’l baby brother crawlin’. I had a older sister and she so good. Many a time when she wasn’t more’n nine year old, I done hold a pine torch for her to see how to wash our rags, at night. We had to sleep on the floor, huddled together so we wouldn’t freeze to death.

“We used to wait outside the kitchen door of massa’s big house. The cook give us all she could, sometimes a teaspoon of syrup and we’d mix it with water to make somethin’ sweet. We was hungry all the time, never did get much to eat no time. Or we’d eat at a biscuit with fried meat grease on it. We’d be too hungry to give the baby his rightful share. We’d git chicken feet where they done throw ‘em out, and roast ‘em in ashes and gnaw the bone.

“My pappy was a blacksmith and could make anything from a horseshoe nail to a gooseneck. He’s sold to Jedge Maddox from the Burkhalters, and pappy allus say they was mean as they come. But Rosa, here, her massa was good to her, wasn’t he, Rosa?

Rosa goes on with her story.

“That’s right. Dr. Andrews was a good man and a good liver. He come from Mississippi but he moved to Union Parish in Louisiana. He brung me and my mama along and told her to piece quilts. They was only twelve slaves and I had all my time to play till I was nine years old. I was the baby of my mama and she had eight older chillen, and Dr. Andrews was good to us and give us good li’l cabins and cotton mattresses and blankets. We had enough to eat, too, and it was ‘lowanced out to us every two weeks, syrup and meal and flour and fat meat and plenty of milk. The madam, that’s Miss Fannie, had a garden and give us fresh greens and things.

“The neighbors used to say, ‘There goes Andrews’ free niggers.’ That’s ‘cause he hardly ever whipped them and give them rest and play time, and took care of us when we was sick. I sho’ thunk a heap of Dr. Andrews.

“When I was nine or sech I went in to the house as waitin’ and nursegirl. The Andrews had two boys and a gal, and I nursed them and waited on Miss Fannie. But they never better cotch me with a book.”

Jack takes up the story.

“On Jedge Maddox’ place if a nigger was cotched with a book he got whopped hard. We had to work when we was right small. The Jedge done move to Mount Enterprise, in Texas, and I worked in the fields. We had to git up ‘fore daylight, ‘cause the overseer, he thunk three o’clock was a good time to git up. I got a li’l more to eat after I was in the fields, but I had to steal most of it, one way and ‘nother. But the older I’d git, the more I larnt the taste of the whip, with my back laid open. I’d go fishin’ and cook and eat them in the woods, so the missus couldn’t take them ’way from me. They found out about it, though, and put a chain around my legs and on my arms and a stick under my knees and chain my hands down to it. I’s hobbled worse’n a animal, and my chains clanked when I’s tryin’ to make a fire for the Jedge, and he got mad and beat me half to death. The he put a iron band and chain round my neck and it choked me terrible. Yes, I’s a white folks nigger. I love ‘em jes’ like dat dog loves a hickory switch!

“They was lots of spec’lators comin’ to Texas them days, and one day Jedge Maddox brung home a purty mulatto gal, real bright and long black hair what was purty straight. The old lady come out the house and took a look and say, ‘What you brung that thing here for?’ Jedge say, ‘Honey, I brung her here to do you fine needlework.’ Missus say, ‘Fine needlework, you hind leg!’

“You know what missus done? When Jedge away from home, she gits the scissors and crops that gal’s head to the skull. I didn’t know no more ‘bout that case, but I do know white men got plenty chillun by the nigger women. They didn’t ask ‘em. They jes’ took ‘em. Rosa’ll tell you the same.

Rosa takes up the story.

“Whoo-ee! Nobody need to ask me. I can tell you a white man laid a nigger gal when he wanted her. Some them white men had a plumb cravin’ for the other color. Leastways, they wanted to start themselves out on nigger women. But master was a good man and I never heard of him botherin’ any nigger women. But they was some redheaded neighbors what had a whole crop of redheaded nigger slaves.

Jack continues.

[…]

“ ‘bout time war come ‘long, I ‘member them days plain. My brother and me went to haul salt from Grand Saline, in Texas. Then I’s sont with mules and more niggers to work on breastworks. I heared the battle of Vicksburg and that was somethin’ to hear, Gawd knows!

“Goin’ home I stopped by Mrs. Anderson’s place. She had a boy named Bob who deserted and was hidin’ at home. Some ‘federate soldiers come by and say they’ll burn the house down lessen he comes out. So he came out and they tied him with a rope and the other end to a saddle and went off with him trottin’ ‘hind the hoss. His mammy sont me followin’ in the wagon. I followed thirteen mile. After a few miles I seen where he fell down and the drag signs on the ground. Then when I come to Hornage Creek I seen they’d gone through the water. I went across and after awhile I found him. But you couldn’t tell any of the front side of him. They drug the face off him. I took him home.

“When I got to Tyler I seen Yankee prisoners they took at Mansfield. Richard Burns and Jimmie Lock was there. But after that when I jined the Federals I seen them all again, ‘cause they ‘scaped out in wheelbarrows, covered with shavin’s.

“I hadn’t been back home long when Jedge got mad and ties my shirt over my head and beats me bloody raw, so I ran away and jined the Federals. We walked through the woods a long time, maybe two weeks, and found them by Monticello, in Arkansas. They give us hardtack and sowbelly and the first coffee I ever drank. It was June 25 and I stayed with that bunch till December of that same year. It was 1865. I went with them to San Antonio and a man named Menger had a hotel and give me a job and a glass of lager beer there. First time I ever had any of that. My job was to haul down to the Yankee camp at San Pedro Spring, right by San Antonio.

“But the itchin’ heel got ahold of me and I started back to Arkansas and worked in a sawmill, and in 1868 I went to Louisiana to work in a new sawmill and met Rosa. I sho’ loved her the first time I seen her.

“We marries and ‘cides to buy a farm and makes a payment on a piece of unclear land. Rosa worked like a man. We sawed trees and split logs and cut shingles and dug our own well. We cleared the land and planted it. We had a baby in ‘bout ten months and I thought everything in the world was fine them. Rosa made all our clothes and knitted my socks and we was livin’ tol’ble well. Then the man we bought the place from died and we found out it didn’t ‘long to us. The children of the man sold the land away from us.

“So we went from tenants to a Louisiana farmer and every year we come out with nothin’ but owin’ that man money. After three years of him ad his son fell out and the son come and told me his paw was beatin’ me on the books. He told me I was a fool not to learn to read and write and so he helps me and I studies every night. When time come for the next ‘greement, I tells the man we’ll keep double books. At end of the year he had me owin’ money but my books showed me nearly a hundred dollars ahead. I tells him figgers don’t lie, but the hand what makes them sho’ could. I never got that money but we parted our ways then.

“I farmed here and yonder and had seven chillen. One boy is livin’ and he’s fifty-one year old. In 1892 I come to Dallas and worked for the Lingo Lumber Company a long time.

“Rosa and me been sweethearts all the time. She’s been the best woman and I never wanted to make no swaps. Its never too cold, never too bad for her to do for me. Course, I ain’t allus been so virtuous. I stepped out the middle the road, but Rosa didn’t take on none.”

“I guess its a man’s nature to do with women, and I guess they can’t go agin they nature. But I allus been good. But daddy’s a right good man. He was good ‘nough to me.

“When we’s purty old we knew a woman with a baby and she treated that baby pitiful bad. Jack ‘members how mis’ble he was when he was a li’l boy and says we can take the baby, so his mammy gave him to us. He’s been with us ever since and he’s fifteen now. He knows the names of the baseball players and the G-men. He’s a fine boy and larns well in school.

“This is the first time Jack and me ever told anybody our story. We ain’t done so much, but the best we could.”

![]()

For more on issues discussed in this post see:

John W. Blassingame, “Using the Testimony of Former Slaves,” Journal of Southern History, XLI no. 4 (1975)

More narratives can be found here at Project Gutenberg

Many narratives have been published:

George Rawick, ed. The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, 26 Volumes

Charles Perdue and Thomas Barden, eds., Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves

James Mellon, ed., Bullwhip Days: The Slaves Remember

Norman Yetman, ed., Voices From Slavery: 110 Authentic Slave Narratives

Photographs:

Rosa and Jack Maddox, Briscoe Center for American History