Private family photographs document events, such as births, marriages, and reunions, that are important in the history of individual families, but they can also teach us about the events we think of as real history. Jewish wedding photographs taken during the Second World War and the Holocaust take us into a world of private family events but also give us new ways to understand the big questions of the twentieth century.

The newly married couple, Herman de Leeuw and Annie Pais, pose with members of the wedding party shortly after the ceremony. [Photograph #08725]

I was surprised to find this photograph. Until I saw it, I did not know that Jews were still getting married in Nazi-occupied Europe or that they were having photographs taken to commemorate the event. I found this picture in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s photographic archive and it is not an isolated example. A search in the museum’s online data base for photographs of Jewish weddings produced 496 responses. The Holocaust Museum archive has photographs of Jewish couples getting married in many different occupied European countries, in foreign exile in Shanghai and Kenya, and in transit camps such as Westerbork, the Dutch way station on the deportation route to Auschwitz, and even in the Warsaw ghetto.

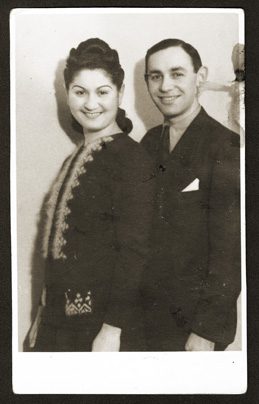

Portrait of a Jewish couple in the Warsaw ghetto taken at the time of their wedding. Pictured are Pawel Tabaczynski and Bela Szrut. The couple married in the Warsaw ghetto in November 1941.

The fact that these Jewish wedding photographs exist at all is quite remarkable. We would probably not expect Jews to be getting married despite Nazi occupation, and the threat of deportation and annihilation. Marriage presupposes an expectation of some kind of future, even in the darkest times. We know that many of the people in these pictures would not survive. Did they have no idea what might soon happen to them? Were they deluding themselves that they would survive? The caption attached to the second photograph here, which shows a couple in the Warsaw ghetto, certainly supports such a reading; “During the suppression of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, they were both deported to the Poniatowa concentration camp, where they perished.” Another picture of a wedding party in Salonika, Greece, taken in 1942-43, tells us that the couple’s “marriage was hastily arranged two months before their deportation so that they might be able to stay together. The couple perished in Auschwitz.” The caption of yet another wedding photograph tells us that no one in the picture survived.

Yet, knowing what happened after these photographs were taken makes it difficult for us to understand what the pictures originally showed. When we look at photographs of Holocaust victims who are still alive in a Polish ghetto we already know that they will soon be murdered, but most of the victims probably did not know their fate. Life in the ghetto was seen as a gamble with the future, a desperate attempt to stay alive long enough for the war to end. We know that this gamble would not succeed. The Jews in these photographs did not.

Recognition of the distance between our “now” and their “then” can allow us to understand why these Jewish couples and their relatives are smiling and why they devoted so much effort and ingenuity to finding the wedding gowns and all the other accoutrements of a “proper” wedding under the extreme conditions of wartime scarcity and Nazi persecution. These Jewish wedding photographs can be seen not as attempts to deny the horrible reality of the Holocaust but as conscious efforts to defy its grotesque abnormality by claiming a small scrap of normality, a tiny hope for the future.

The bride and groom, Victoria Sarfati and Yehuda (Leon) Beraha, pose with family members at their wedding.

Pictures of Jewish weddings might also suggest that Jews could sometimes use photography to challenge the vicious anti-Semitic images produced by Nazi propaganda. In these private photographs, Jews showed themselves as they wanted to be seen, not as the Nazis portrayed them. This does not mean that we should see these wartime wedding photographs as a previously undiscovered form of resistance to Nazi tyranny, but it does mean that we can see attempts to claim private happiness as something more than irrelevant, futile or misguided gestures.

If you want to learn more about these photographs, you can start at The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; or you can read, The Years of Extermination. Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945 (2008) by Saul Friedländer.

Photo info and credits:

Figure 1.

Date: 1942

Locale: Amsterdam, [North Holland] The Netherlands

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Samuel (Schrijver) Schryver

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Figure 2.

Date: Nov 1941

Locale: Warsaw, Poland; Varshava; Warschau

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eugenia Tabaczynska Shrut

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Figure 3.

Date: 1942 – 1943

Locale: Salonika, [Macedonia] Greece; Saloniki; Salonica; Solun

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mary Beraha Rouben

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum