This is part of an occasional series of articles highlighting the fascinating collection of historical documents in the Briscoe Center for American History at UT Austin.

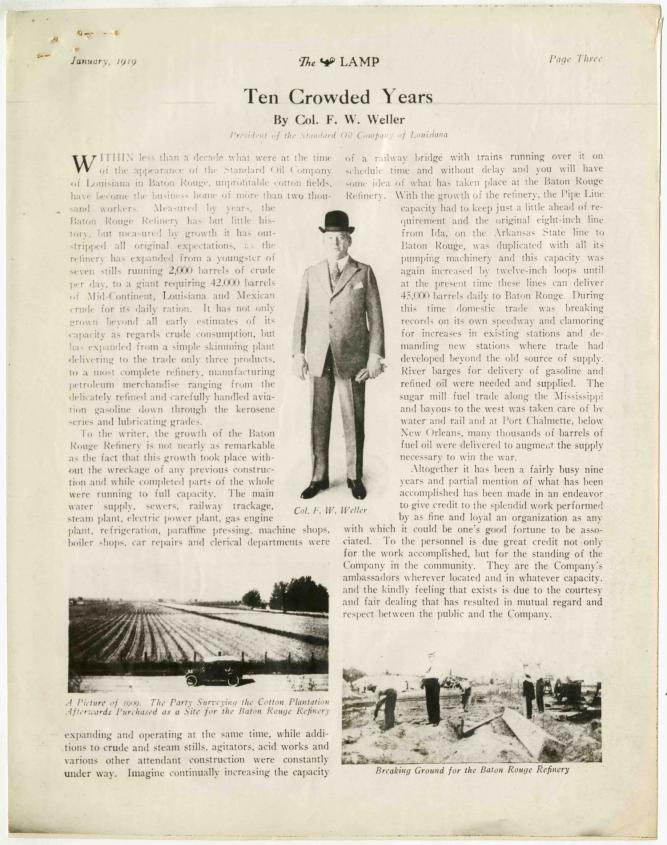

The January 1919 edition of The Lamp, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey’s nationally circulated trade publication, marvels at the firm’s gleaming new refinery in Baton Rouge. After being spun off from John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, the newly independent company was eager to grow its business in the Bayou State. And the Baton Rouge plant had done just that, becoming an enormous industrial concern refining over 40,000 barrels of crude each day.

This issue of The Lamp, which Standard Oil-NJ sent to its employees, stockholders, and outside subscribers, tries to assuage contemporary anxieties over big business by celebrating the economic development and social uplift occurring in Louisiana. Thanks to company investment, a productive and modern industry is replacing fallow cotton fields and the primitive, old ways they represent. The Lamp even presents Baton Rouge’s new refinery as an agent of Post-Reconstruction reconciliation, a harmonious project of regional collaboration between northern expertise and southern natural resources. Oil refining represents nothing less than societal transformation: a “New South” of productivity, sectional reconciliation and affluence, all brought to Louisianans by the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

Company photographs depict Louisiana as a landscape in transition—a space where farming is slowly giving way to modern industry. Under the title, “The Transformation of the ‘New South’ Under the Magic Wand of Industry,” two large horizontal photographs spread parallel across the page. The top image depicts a 1909 cotton plantation of overgrown weeds and ramshackle fencing set against a winding dirt road. The photograph directly below displays the same patch of land ten years later, where an enormous refinery dominates the horizon and bears no mark of any agricultural predecessor. This striking visual comparison offers a clear and proud juxtaposition: the old giving way to the new.

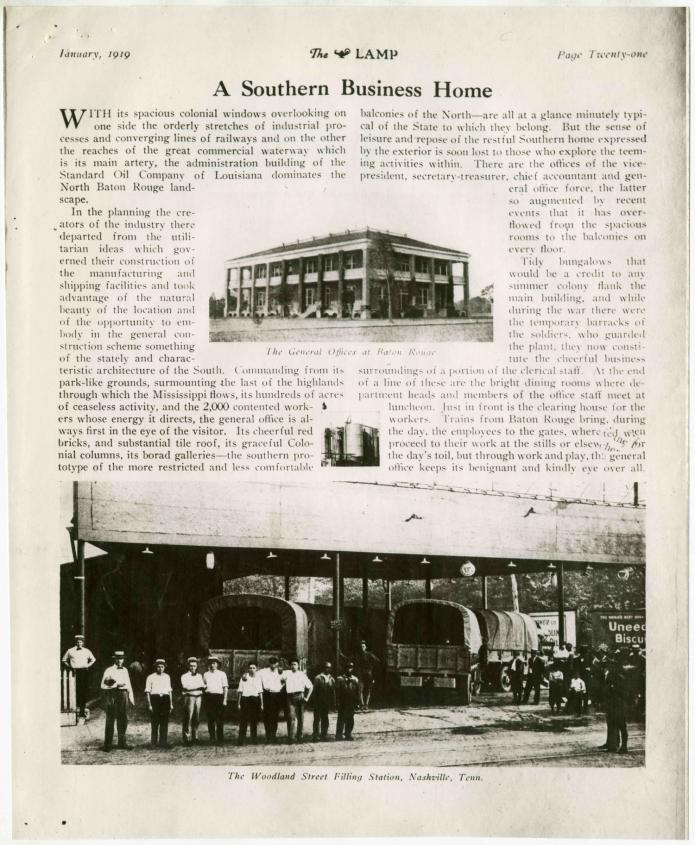

By working towards a future of economic modernity, Louisiana was also escaping a legacy of north-south antipathy. The Lamp depicts the refinery as a national project in which northern industry and southern land work in concert towards a productive future. “A Southern Business Home,” which discusses the company’s Baton Rouge headquarters, inscribes this language of regional partnership into the building’s very architecture. Elegant colonial windows look upon orderly refining processes and converging railway lines, creating a dynamic interplay between old world repose and modern productivity. Standard Oil-NJ’s headquarters physically embodies peaceful collaboration: the industry and expertise of the north working alongside the abundant lands and bucolic lifestyle of the south. Even as pipelines and factories consume more and more Louisiana bayou, the form and style of Standard Oil-NJ’s development promotes an image of peaceful coexistence with the southern landscape.

Yet despite all the enthusiasm for the company’s role in Louisiana, The Lamp also conveys a quiet anxiety as it ponders the bucolic, pre-modern past that industry is steadily replacing. Photographs and articles simultaneously celebrate industrial change and commemorate the people and lifestyles that are vanishing as refineries engulf plantations. In “Pipe Lines in the South,” C.K. Clarke, manager of the company’s Pipe Line and Producing Department, describes the intersection of industrial expansion and romantic traditions in Louisiana, whimsically imagining Standard Oil’s pipelines stretching within sight of Uncle Tom’s cabin. Although Clarke concedes that Louisiana’s old ways are incompatible with the modern world, he strikes a nostalgic tone as he considers the lamentable, if necessary, end to a romantic, pre-modern time.

For just a moment, The Lamp‘s narrative of progress and optimism pauses to consider the consequences of industrialization. The company publication creates a wistful historical record of the wild landscapes and wild characters of the “Old South” before they disappear—a kind of strange recompense for its own role in their destruction. Changes in land use represent progress, but also the end of an era. To be sure, this is a “history” told entirely on company terms, reinforcing the backwards and fundamentally un-modern character of old Louisiana. But it does suggest that Standard Oil-NJ officials were, at very least, conscious of their public—and historical—image. The Lamp accordingly presents company men not as mindless capitalists, but as thoughtful stewards of the past, rightly or not.

Amidst a national climate of anti-monopolism and trust busting, The Lamp unapologetically promotes the benefits of big business in Louisiana. Articles and photographs celebrate rapid changes to the state’s landscape as symbols of progress and betterment. Pipelines and refineries engulfing cotton fields augur a “New South” of industry, profitability and sectional reconciliation.

But for all the confidence its narrative exudes, The Lamp cannot help but consider what is being lost in the march to modernity. Company officials remain deeply fascinated by the vanishing “Old South” and the nostalgia it conjures. At certain moments, The Lamp reads like a romantic history book, chronicling the quaint ways of the old bayou before it becomes just another factory. While the employees of Standard Oil-NJ are undoubtedly proud of their work in Louisiana, they remain highly attuned to contemporary fears over industrialization and its potentially corrosive impact on American society. The Lamp is ultimately both confident and defensive: optimistic about the future Standard Oil-NJ is creating and nostalgic for the past it is destroying.

Photo Credits:

Selected pages from the January 1919 edition of The Lamp

The ExxonMobil Historical Collection

di-09040, di_09041, di_09042

The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

***

You may also like: