By Ann Twinam

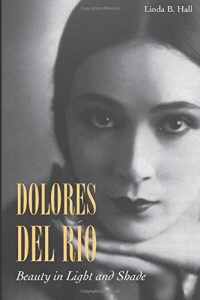

Linda Hall provides a compelling biography of one of the most famous and beautiful women of the twentieth century: actress Dolores del Río. She traces critical stages from del Río’s sheltered life as a daughter of a Mexican elite family to her early marriage and transition to Hollywood starlet in the 1920s, where she figured in silent and then talking pictures; to her return south where she became a pivotal actress of the Mexican “Golden Age of Cinema” of the 1940s. In later decades, technology revived del Río’s celebrity, when a new generation viewed her film performances on the newly-invented television.

Hall concentrates on del Río’s professional and personal life through analysis of letters, interviews, film contracts and posters, movie reviews, and local newspapers. These track the ups and downs of her career, her multiple husbands, her real and possible lovers, and her famous friends. Woven throughout, are the pervasive themes of how gender, sexuality, race, transborder crossings, changing technologies and celebrity defined del Río’s career.

Every camera loved Dolores del Río. Still, a persistent theme running throughout her career was the continuing mandate to negotiate even her astonishing beauty through the constraints of class, gender, race and Mexican-ness. After her 1925 arrival in Hollywood she, her directors and the studios emphasized her origins as an elite Mexican, her status as a lady playing ladylike parts. In later years, with her celebrity assured, she assumed roles that more emphasized her sexuality or challenged racial norms as she portrayed Native women. When Hollywood parts diminished, del Río returned to Mexico in 1942. She collaborated with director Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez and co-star Pedro Amendáriz to produce some of the classics of Mexican cinema including Maria Candelaria. She sporadically revisited Hollywood including a cameo in 1960 playing the Indian mother of “Elvis.”

Del Río was not only herself a celebrity, she moved in the circles of the famous. Hall traces Hollywood business and social friendships that included Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, and William Randolph Hearst. Del Río also maintained her transborder contacts with Mexico, as she counted Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, Pablo Neruda, Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez, and co-star Pedro Armendáriz among her intimate friends.

If there is any flaw in this marvelous biography, it seems rooted in the very ambiguities and opaqueness of del Río’s life. She never wrote an autobiography. Hall deftly surmounts such challenges by writing “around” the business and personal life of del Río, although questions remain. How did she overcome the dominance of husbands, directors and studios to chart her own path? Were her first two husbands gay? Did she engage in affairs with Greta Garbo or Frida Kahlo? How much wealth did she eventually accumulate, given the fabulous sums paid to pre-depression stars?

Linda Hall has offered an engaging look into what historians can likely uncover of this enigmatic star. She concludes that del Río “led a rich, fulfilling up-and-down life that was unusual largely because of her celebrity, her great wealth, her beauty and ultimately her power to shape her own destiny.” Hall’s book proves to be a fascinating resource for readers interested the history of women, gender, sexuality, transborder crossings, celebrity, and film.

Linda Hall. Dolores del Río: Beauty in Light and Shade. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Also by Ann Twinam on Not Even Past:

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America.

15 Minute History Episode 52: The Precolumbian Civilizations of Mesoamerica.

No Mere Shadows: Faces of Widowhood in Early Colonial Mexico, by Shirley Cushing Flint (2013).