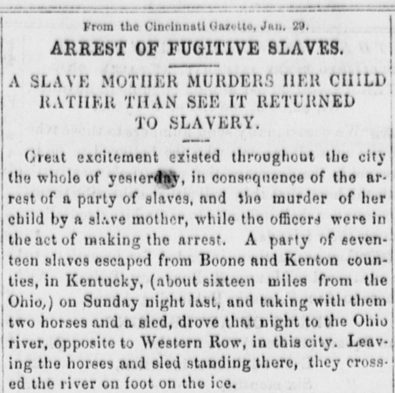

In January of 1856, a prolonged period of frigid temperatures in northern Kentucky—the coldest in sixty years—froze the Ohio River creating a bridge to freedom for enslaved people daring enough to cross it. On Sunday, January 27, 1856, Margaret Garner and seven members of her family made the arduous eighteen-mile journey that separated their lives of enslavement in Kentucky from freedom in Ohio. After only a few hours on free soil, the Garners found themselves facing imminent capture. When the chaos subsided and the Garners were subdued, Mary, a toddler, lay dead and the Garners’ three surviving children all bore wounds of various degrees and intensity. Margaret had attacked her own children. Examining the events that shaped Garner’s decision and the subsequent legal battle that propelled her, if only briefly, into the national spotlight, Nikki M. Taylor offers a nuanced study of Margaret Garner’s life and the impact of the trauma of enslavement on the enslaved.

The title of Taylor’s work suggests a causal relationship between slavery and the “madness” that inspired Garner to kill her daughter. In the introduction, Taylor asserts unequivocally that “slavery caused trauma.” This is a significant aspect of Taylor’s analysis as she argues that understanding Margaret Garner’s trauma is critical to understanding her reaction to the threat of capture. When federal marshals and the Garners’ enslavers surrounded the house where the Garners hid, Margaret and Robert both reacted violently—Taylor, however, reads an important distinction into their respective actions. Robert, using a pistol stolen from his enslaver, fired at the slave catchers as they forced their way into the house. Margaret also responded with deadly force, but unlike Robert, Margaret’s attention focused inside the house. Taylor cogently applies trauma theory first espoused by Sigmund Freud and later expanded by Cathy Caruth to examine this gendered distinction.

Driven Toward Madness explores the intimate aspects of Margaret Garner’s life and fleeting celebrity by tracing the arc of the Garners’ flight, capture, legal controversy, and removal to Louisiana. Taylor insightfully considers the psychological effects of enslavement and sexual abuse and the meaning of infanticide in asking whether murder can be considered resistance. Reconstructing Garner’s life from interviews and articles published in contemporary newspapers, fugitive slave hearings, criminal indictments, and personal papers, Taylor employs a variety of methodological approaches that integrate black feminist theory, trauma studies, pain studies, genetics, history of emotions, and literary criticism to explore the trauma Garner experienced as an enslaved woman, and the violence that Garner endured and enacted. Taylor’s focus on the interconnected themes of motherhood, sexual vulnerability, trauma, and violence, and her attention to Garner’s mental state and perceived psychological trauma push slavery studies into new territory—the psychological impact of enslavement on the enslaved—that until recently has remained under-explored. This interpretative approach presents a challenging line to walk—one that requires the historian to stay true to the extant records yet acknowledge the unavoidable silences and absences within the archive that often obscure enslaved women’s lives. The result is a work that reconsiders enslaved motherhood and how we conceptualize resistance.

Although the specific nature of the violence Garner experienced at the hands of Archibald Gaines is absent from the written record, Taylor persuasively reconstructs a psychological profile of the enslaver. She painstakingly tracks recorded incidents of his violent temper to establish that Gaines was prone to violent outbursts. She describes the scars on Margaret’s face, as evidence of violence that was both up-close and personal; those scars offered silent testimony to the physical abuse she endured.

Margaret’s reproductive history tells of another kind of abuse. Describing Margaret as “perpetually pregnant” from the birth of her first child in 1850 to her escape in 1856, Taylor documents Margaret’s pregnancies as evidence of the sexual abuse she likely experienced. This is perhaps Taylor’s most impressive analytical work. Building on the method of reading the record Annette Gordon-Reed used in her ground-breaking study of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, Taylor establishes the probability that Gaines fathered at least two of Margaret’s children. Enslaved within different households, Margaret and Robert lived apart. They had what was commonly known as an “abroad marriage.” This meant that their time together was often infrequent and subject to their enslavers’ discretion. Additionally, Robert was often hired out, resulting in frequent and prolonged absences. Citing these absences, Taylor questions the paternity of the child in Margaret’s womb and her two youngest children, Mary and Cilla, who were often described as so fair they appeared white. To support the assertion that Gaines likely impregnated Margaret, Taylor engages in genetic analysis that includes a detailed examination of the probability that Robert (a dark-skinned man) and Margaret (a light-skinned woman) produced two extremely fair-skinned children. Taylor acknowledges the imprecise nature of this type of analysis—but her discussion of genetics, skin color, sexual abuse, court testimony, masculine honor, community complicity and silence, and sexual access point to an answer.

Driven Toward Madness is well-written and thoroughly researched. For scholars of slavery, Taylor’s examination of Margaret Garner’s life within the midwestern community of small-slaveholding households is an insightful examination of motherhood, sexual abuse, violence, and trauma created by the institution of slavery. She brings into clear focus the political implications of the jurisdictional conflict between national and state authorities concerning the Fugitive Slave Law and federal authority that contextualized Garner’s prosecution. Taylor’s work attempts to fill the substantial silences in the record that point to what is ultimately unknowable—that is, how enslavement traumatized Garner to the extent that when faced with capture, Garner picked up a knife, and then a shovel, and attacked her children rather than see them return to enslavement.

More Post You Might Like:

Empire of Cotton

Slavery in Indian Country

Slavery and its Legacy in the United States