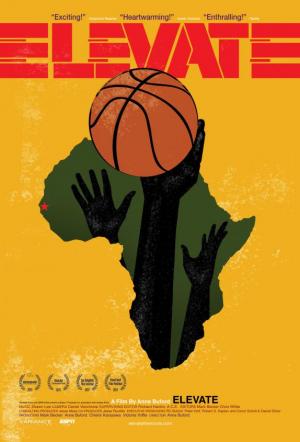

Anne Buford’s documentary Elevate focuses on several Senegalese youths and their attempts to make it out of Senegal through basketball. Through the compelling narratives of each of the Senegalese students portrayed in the insightful documentary,  we witness the trials and tribulations of urban youths trying to move beyond the difficulties that they face in their daily lives in Senegal. The documentary begins at the SEEDS Academy, the project of Amadou Gallo Fall, a personnel director for the Dallas Mavericks. Essentially, the SEEDS Academy is described as an attempt to create a boarding school for Senegalese youths to hone their basketball and academic skills and eventually (hopefully) receive a scholarship to play basketball at a prestigious prep school in the US. Beyond this, each of the young Senegalese students profiled in the ESPN funded documentary hope to play college basketball and eventually make their way to the NBA.

we witness the trials and tribulations of urban youths trying to move beyond the difficulties that they face in their daily lives in Senegal. The documentary begins at the SEEDS Academy, the project of Amadou Gallo Fall, a personnel director for the Dallas Mavericks. Essentially, the SEEDS Academy is described as an attempt to create a boarding school for Senegalese youths to hone their basketball and academic skills and eventually (hopefully) receive a scholarship to play basketball at a prestigious prep school in the US. Beyond this, each of the young Senegalese students profiled in the ESPN funded documentary hope to play college basketball and eventually make their way to the NBA.

While soccer is the predominant leisure sport in much of West Africa, efforts like that of Amadou Gallo Fall are making basketball appear to be a gateway to prestige and socio-economic advancement for individuals like Assane, Aziz, Dethie, Byago, and their Senegalese peers. Thus, youths who have never played basketball before are beginning to pick up the sport in increasing numbers. In the documentary, viewers see the immense amount of training and preparation leading to evaluations that eventually decide whether these hopefuls receive a coveted scholarship position at a U.S. prep school. Despite this, the students portrayed in the documentary were often unprepared for what they would experience in America. Feelings of isolation were prominent throughout the documentary, especially among Senegalese students when they were the only “outsider” in a school filled with socio-economically privileged American students.

Anne Buford, a first-time documentarian, does an exceptional job of capturing the students’ discomfort in their encounters with the American academic system and predominantly white youth culture. In the course of the film, we see students fighting to bear the cold weather, trying to “fit in,” and struggling in their coursework due to

the fact that these students primarily speak French. Some of the most intriguing moments in the documentary involve issues of religion and alienation in the new environments that surround these young students. Both Assane and Aziz are Muslim and it is evident that in both of their respective schools, practicing Islam is not well understood by their peers. This is particularly poignant in a dining hall conversation that Aziz has with one of his schoolmates who knew little about Ramadan, but was curious why Aziz was abstaining from eating during their mealtime. We later see Aziz breaking fast alone in his dorm room. Buford also captures a sense of Assane’s religious isolation in her juxtaposition of school-wide church services in the religiously-affiliated prep academy and his solitary prayer sessions in his dorm room. Despite these difficulties, at one point, Dethie lands a position at the same school as Assane. As a result, Assane is able to guide him through such a large cultural, physical, and mental transition. In the end, we are left with a bittersweet message of hope. All of the students in the documentary continued their education in the United States and played basketball at the college level at schools ranging from Carroll College in Montana to the University of Virginia where Assane was a starting center.

the fact that these students primarily speak French. Some of the most intriguing moments in the documentary involve issues of religion and alienation in the new environments that surround these young students. Both Assane and Aziz are Muslim and it is evident that in both of their respective schools, practicing Islam is not well understood by their peers. This is particularly poignant in a dining hall conversation that Aziz has with one of his schoolmates who knew little about Ramadan, but was curious why Aziz was abstaining from eating during their mealtime. We later see Aziz breaking fast alone in his dorm room. Buford also captures a sense of Assane’s religious isolation in her juxtaposition of school-wide church services in the religiously-affiliated prep academy and his solitary prayer sessions in his dorm room. Despite these difficulties, at one point, Dethie lands a position at the same school as Assane. As a result, Assane is able to guide him through such a large cultural, physical, and mental transition. In the end, we are left with a bittersweet message of hope. All of the students in the documentary continued their education in the United States and played basketball at the college level at schools ranging from Carroll College in Montana to the University of Virginia where Assane was a starting center.

The documentary could have delved more into socio-economic inequality, especially regarding neocolonialism and limited opportunities for advancement in the post-colony. While we briefly witness the Senegalese communities from which Assane, Dethie, Aziz, and Byago emerged, I would be interested in seeing more about the Senegalese education system and avenues for advancement outside of sports as a way of contrasting this with the relatively new establishment of the SEEDS Academy.

Ultimately, however, this film captures an intriguing cultural exchange that embodies our era of globalization. What may seem like a documentary on a seemingly universal sport ultimately emphasizes understandings (and misunderstandings) of both the west and Africa. Even the sport of basketball is a different game in the United States, where there is a greater emphasis on shooting instead of defense. Nevertheless, these Senegalese students have quite a bit in common with other student athletes from throughout the United States — they are all searching for opportunities for advancement despite seemingly impossible odds. Despite the odds, their dreams of success in the NBA and hopes of bringing their families to America or their wealth back to Senegal live on.

Photo Credits:

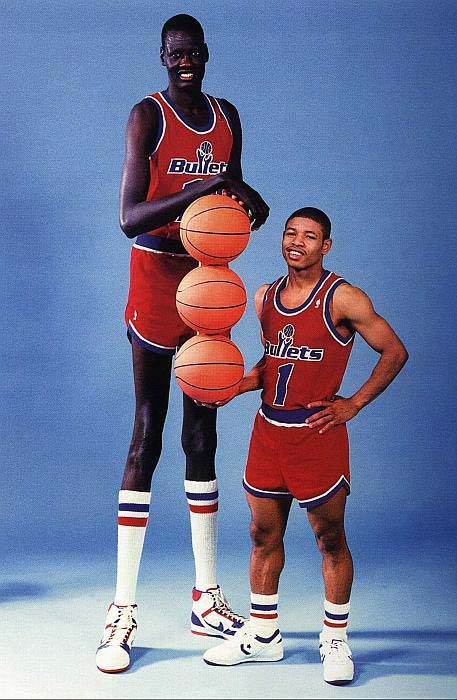

Manute Bol, a Sudanese born center for the NBA’s Washington Bullets, stands next to his teammate, guard Muggsy Bogues, during the 1987-88 season. Bol and Bogues were, respectively, the tallest and shortest players in the NBA at the time. (Image courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

You might also like:

This recent NPR story about Sudanese teenagers moving to Illinois to play basketball