Ralph Peer shook his head. A scout for the Victor Talking Machine Company in the 1920s, he could not believe the number of white southern singers who dug commercial popular music. “They would come in to me, people that could play a guitar very well and sing very well, and I’d test them. ‘What other music have you got?’ Well, they’d sing some song that was popular on record, some pop song,” he recalled. “So I never bothered with them. They never got a chance.” Dorothy Scarborough shared Peer’s impatience. After collecting African-American folk songs throughout the South in the early 1920s, the white scholar lamented, “How often have I been tricked into enthusiasm over the promise of folk-songs only to hear age-worn phonograph records,—but perhaps so changed and worked upon by usage that they could possibly claim to be folk-songs after all!—or Broadway echoes, or conventional songs by white authors!”

Black Mississippi guitarist Robert Johnson knew lots of songs by white authors. He played them whenever he could. “Robert didn’t just perform his own songs,” his friend Johnny Shines insisted. “He did anything that he heard over the radio. ANYTHING that he heard. When I say anything, I mean ANYTHING—popular songs, ballads, blues, anything. It didn’t make him no difference what it was. If he liked it, he did it.”

Southern musicians performed a staggering variety of music in the early twentieth century. Black and white artists played blues, ballads, ragtime and string band music, as well as the plethora of styles popular throughout the nation: sentimental ballads, minstrel songs, Tin Pan Alley tunes, and Broadway hits. They embraced pop music. Many performed any music they could, regardless of their racial or regional identities. Such variety could appear in the same set as a performer eased from one song to the next. Observers agreed that rural southerners loved all sorts of music. Yet they fought about whether that was a good thing. Scarborough and Peer were not pleased to discover Broadway in the backwoods. A southerner singing pop music was the last thing they wanted to hear.

The meaning and symbolic power of southern music was radically transformed between the 1880s and the 1920s, an era that saw the development of southern segregation, the globalization of US political and corporate empires, and the dissemination of commercial sheet music and phonographs across the nation. During this period, a variety of people—scholars and artists, industrialists and consumers—came to compartmentalize southern music according to race. A fluid complex of sounds and styles in practice, southern music was reduced to a series of distinct genres associated with particular racial and ethnic identities. Music developed a color line. The blues were African-American. Rural white southerners played what came to be called country music. And much of the rest of the music performed and heard in the region was left out. By the 1920s, these depictions were touted in folksong collections as well as the catalogs of “race” and “hillbilly” records promoted by the phonograph industry. Such simple links among race, region and music were new. They did not reflect how generations of southern people had understood and enjoyed music. Johnny Shines emphasized Robert Johnson’s broad repertoire in a repetitive cadence designed to overcome doubters. His insistence suggests how thoroughly the logic of segregated sound had become common sense—even while most observers acknowledged that it failed to reflect the music actually played and heard by southern people.

The musical color line stretched from the library shelf to the record catalog, from the tent show to the concert hall. The power of folklorists and phonograph companies to control public imagery and shape public perception was far more profound than the power of often-marginalized musicians to counter such claims. Moving from live to recorded performance, from local to national audiences, southern artists jettisoned the broad repertoires that had won them local success. They instead found favor by actively personifying the racial musical categories the academy and the phonograph industry associated with a southern culture defined through its primitivism, exoticism, and supposed distance from modern urban culture.

Artists responded to this conundrum in different ways. Some contested the images created around them, attempting to break their expressive culture out of the confines of commercial and scientific classifications. Others, however, embraced the role of pre-modern primitive. It expressed some of their own misgivings about a modernism based upon their exploitation. Many who came to represent traditional culture, in fact, were not pre-modern but had experienced modernization at its most brutal: sharecroppers, factory workers, and prison laborers. Playing the role of the pre-modern offered them both a voice with which to challenge their conditions and a possible ticket out. Many, however, remained aware that they were entering into a bargain that denied their human and artistic freedom. They stopped singing many of the songs that brought them joy. They pretended their lives could be contained by the categories that confronted them, knowing all along that they owned a world much larger than the one they portrayed. Unearthing their stories can lead us to visualize musical and cultural categories as points of contention rather than assumed points of departure, vibrant subjects for historical research rather than ways in which to limit one’s scope of inquiry. It also can help explain the joyful defiance of singers like Robert Johnson, who gleefully performed anything. And when I say anything, I mean ANYTHING.

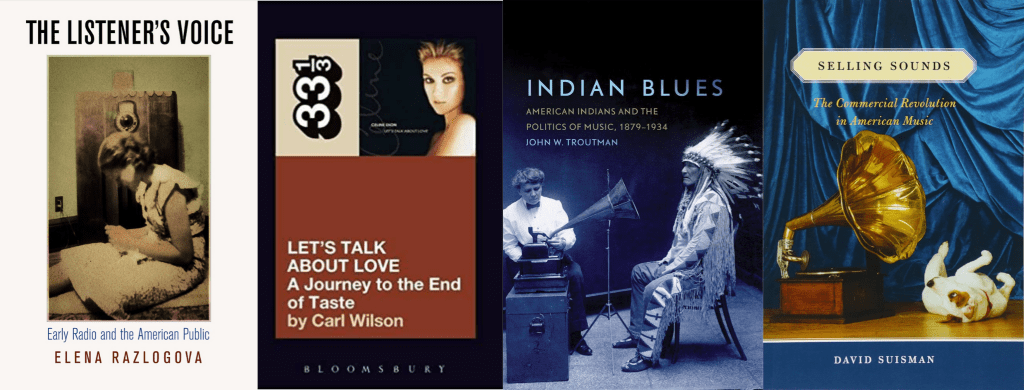

David Suisman, Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music, (2009).

An essential book for anyone interested in the history of popular music in the United States, Selling Sounds charts the emergence of a cohesive—and ubiquitous—music industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The fascinating characters that populate Suisman’s story are no lovers of music. They are savvy businessmen who learned how to transform disembodied sound (whether on sheet music or phonograph records) into hard cash. They also set the template for how music would be marketed for the next 100 years. No book tells the story better.

Elena Razlogova, The Listener’s Voice: Early Radio and the American Public, (2011).

Radios became common in American homes during the 1920s. They brought the world into the family room in unprecedented ways. While much of scholarship on radio focuses on the establishment of major national broadcasting networks, The Listener’s Voice reveals the rollicking world of US radio before the majors seized control. Early radio often depended on its listeners to provide content. Through phone calls and letters, listeners created thriving participatory communities over the air. It was more akin to the vibrant world of early internet forums than to the homogenizing, on-way transmissions of later radio and television networks.

John W. Troutman, Indian Blues: American Indians and the Politics of Music, 1879-1934, (2009).

This wonderful book addresses some of the themes I explore in Segregating Sound—music, race, folklore, and money—from a different angle. Indian Blues tells the fascinating story of the struggle over music and musical meaning between government officials, teachers, and Native Americans in the early twentieth century. While government sponsored programs on reservations and in Indian boarding schools used music as a means to suppress Native resistance and collective memory, many Native Americans used music—be it traditional, new commercial pop styles, or combinations of both—to assert Native autonomy, escape the confines of government proscriptions, and get paid. Fresh, innovative, and well told, Indian Blues offers a story you won’t find anywhere else.

Carl Wilson, Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, (2007).

This is a slim book about pop diva Celine Dion’s top-selling album featuring “My Heart Will Go On,” better known as the theme from the movie Titanic. It is also one of the best pieces of music writing I have read in years. Wilson, the pop music critic for the Toronto Globe and Mail, admits he is not a Dion fan. He then systematically explores her global appeal to discover what he might be missing. The result is brilliant meditation on aesthetics, taste, cultural politics, and pop music history. At times touching and often hilarious, this beautifully written book changed the way I hear music.

Photo Credits:

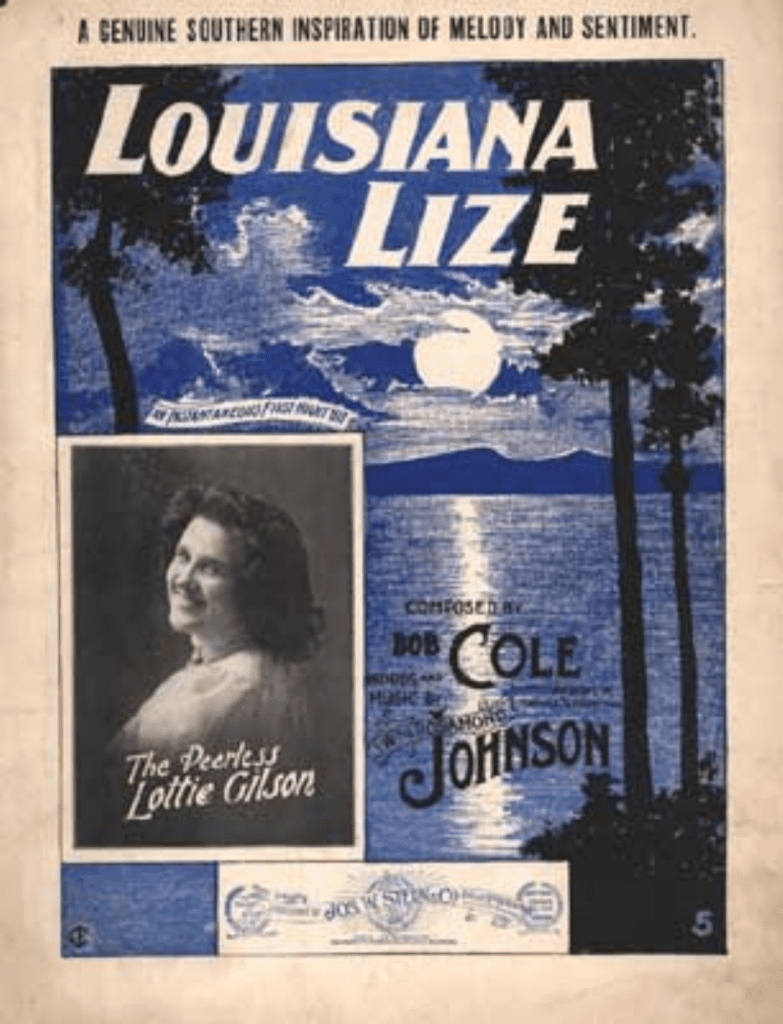

Bob Cole, James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosemond Johnson, “Louisiana Liz” (New York: Joseph Stern & Co., 1899).

Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter and Fletcher Henderson, “Down South Blues” (New York: Down South Music Publishing Company, 1923).

Perry Bradford, “Crazy Blues,” (New York: Bradford Music Publishing Co., 1920).