“Considering how likely we all are to be blown to pieces by it within the next five years, the atomic bomb has not roused so much discussion as might have been expected.” – George Orwell, 1945.

In 2020, an extensive collection of atomic bombing photographs was acquired by UT Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History. Donated by the Anti-Nuclear Photographer’s Movement of Japan (ANPM) a selection of these images are currently on display at the center until January 28. The photographs also form the basis for the Briscoe’s recent publication Flash of Light, Wall of Fire.

The title of both the book and exhibit is taken from a speech made by President Barack Obama in 2015 when he became first American president to visit Hiroshima. During his keynote address, Obama referred to the bombs as “terror fell from the skies.”[1] This remark unfortunately offended many of the Hibakusha (Japanese survivors of the bombings). “You see Ben, the bombs didn’t ‘fall.’ They were deployed, used, thrown,” explained a member of the ANPM to me while visiting Hiroshima in 2018. “They were used by someone on someone else. Us. Americans talk about them so passively, as if they just ‘fell’ from the sky.”

Obama’s blunder was a very American faux pas, and in line with longer trends. As the historian Mark Selden has argued “compelling photographic images detailing the human consequences of the bombing of Japanese cities remained hidden from American view” for much of the post war period. [2] Instead, of despairing mothers and charred children, the dominant American image of the bombings is the mushroom cloud, which in words of James Farell, suggests an “unmediated natural phenomenon . . a new but natural event, free of human agency.”[3] This lack of human (let alone American) agency remains embedded in American memory of the atomic bombings to this very day.

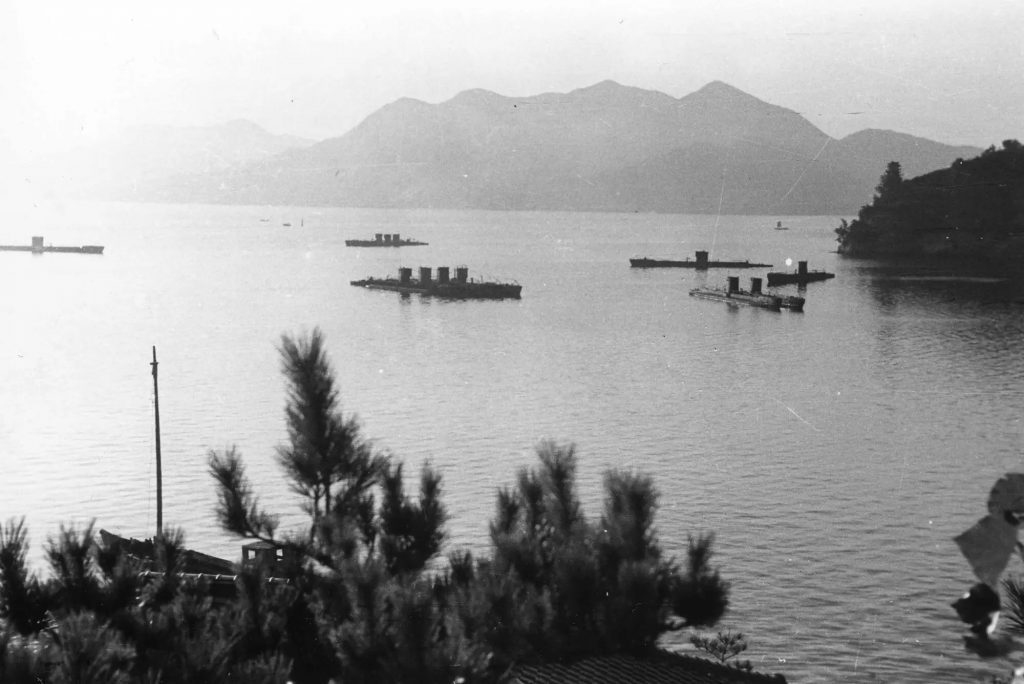

Japanese photographers were quick to document the atomic bombings in their immediate aftermath. For example, Yoshito Matsushige woke up bloodied on the floor of his house in Hiroshima and got to work two hours after the first blast on August 6. Yosuke Yamahata, was in Nagasaki by August 10, the day after the second blast and clambered over the dead and dying, increasingly alarmed by the carnage he witnessed, as he made his way to the blast hypocenter. Others followed in the ensuring weeks before the American occupation ramped up and clamped down. From the American perspective, details of the human suffering that resulted from atomic bombings were military secrets and a threat to public order in occupied Japan. American forces subsequently confiscated photographs and prohibited their publication. In response, many Japanese photographers hid their negatives in lockers and trunks, even under their porches.

In 1952, when the Americans left, a series of books and magazine articles appeared almost instantaneously. First, The Asahi Graph featured a set of images by Matushige and Yamahata. The feature caused a sensation with over 700,000 copies being sold within weeks. It was the beginning of what the sociologist Akiko Hashimoto has termed a “memory boom” in Japan. Today, such images form a bedrock of Japanese public memory about the atomic bombings. However, they have remained unpublished, and largely unknown in America.

How might these photographs have changed and challenged American debate about nuclear weapons? We don’t know. But certainly, there exists here what the historian Wendy Lower calls, “the presence of absence.” By way of contrast, we know how incredibly important photography was to the American Civil Rights movement. Images of human suffering and flagrant injustice galvanized activists, politicians and voters to pursue change. They also provide a rich visual heritage today. However, the American memory of the atomic bombings has remained stunted — in part, I argue, due to a comparative lack of visual resources.

Perhaps the most compelling example of this came in 1995 when the Smithsonian agreed to exhibit the Enola Gay, the aircraft from which the first atomic bomb was deployed. The museum system had planned to exhibit the plane as the centerpiece of a wider exhibit that explored the atomic bombings and included Japanese photographs. However, a furor ensued as politicians, activists and veterans clashed mightily over the exhibit’s details. This was more than just another front in the culture wars of the 1990s. The very reputation of America as a just and peaceful nation seemed to be at stake. In the end, their presence raised uneasy questions for too many Americans. The Enola Gay was instead exhibited quietly and simply by itself.

Photographs represent a compelling visual account of events. They have an aesthetic, visceral and at times mythic quality—mythic in the sense of conveying too much rather than too little. As such, some of these images have become iconic — instantly recognizable. And yet, by no means is the evidence they contain any more pure or unadulterated than that found with other types of primary sources. This is precisely what makes them so interesting. They are not passive recordings of the events, but active renderings embedded with choices — omissions, abbreviations, staging — and raw emotional power. Finally, they have a life of their own. Portable and replicable, they travel and transmute according to the discourses that deploy or repress them. They can be read like texts, but they also come with texts — photographers’ notes, annotations, associated correspondence, slugs, and so on. As evidence, texts, archives and (to an extent) agents, they are integral to the public memories of the events they depict.

When it comes to Japanese photographs of the atomic bombings, they are a form of trans-pacific knowledge that have led dual lives either side of the ocean. Their deployment in Japan has been used to communicate the tragic human suffering that nuclear weapons cause. However, according to John Dower, they have also been used to emphasize Japanese suffering at the end of World War II, over atrocities committed during the war.[4] Meanwhile, their lack of deployment in America has supported a range of discourses, from the triumph of American science to the moral purity of America’s involvement in World War II. Thus, these photographs have a sort of agency — or at least a history — of their own. Through their presence and their absence, they have helped shape both public memory and public policy.

In an age of rising tensions between global superpowers, Flash of Light: Wall of Fire can offer a powerful reminder of the havoc and tragedy that even relatively small nuclear weapons can wreak upon civilians. It is my hope, as a graduate student, historical curator and parent, that they can become fundamental, rather than ornamental, to our understandings of the risks and dangers that such weapons still pose.

Ben Wright is a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. He received his MA in Modern history from King’s College London in 2008. Currently, he works for UT’s University Marketing and Communications and pursues his PhD part time. His research focuses on combat journalism between 1917 and 1989. In 2017, while working at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History, Ben curated the center’s exhibit, “From Commemoration to Education: UT’s Statue of Jefferson Davis.” He has also curated “1968: The Year the Dream Died” and was a co-curator of “Struggle for Justice: Forty Years of Civil Rights photography” and “Flash of Light, Wall of Fire.”

[1] https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00233/president-obama%E2%80%99s-hiroshima-speech-an-assessment.html

[2] See Selden’s introduction to O’Donnell’s Japan 1945. See also Kyoko and Mark Selden, The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki Book (1989)

[3] . James J. Farrell, “Nuclear Friezes: Art and the Bomb from Hiroshima to Three Mile Island,” Twenty/One: Art and Culture (Fall 1989)

[4] John Dower “The Bombed: Hiroshimas and Nagasakis in Japanese Memory.” Diplomatic History 19, no. 2 (1995): 275-95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24912296.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.