By Sumit Guha

It was the Indian month of Shravana, and early summer rains of 1653 would have set in as the delegation of villagers toiled up the steep slopes to the gates of the fort of Rohida, (later named Vicitragadh) and presented themselves to the officials there. They came into the court of Dhond-deu, the Hawaldar – an officer charged with the general fiscal and administrative control of the villages subordinate to the fort. These were turbulent times in western India as the Mughal empire from the north began to slowly conquer the southern kingdoms based in Bijapur and Golkunda. Locally a young lord, Shivaji Bhosle, was gradually adding fort after fort to his domains and planning the creation of an independent kingdom. The officers seated around Dhond-deu must have heard many tales of strife before this time. But this one was stranger than usual.

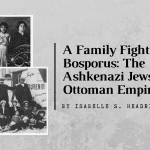

“The fort gateway was probably elaborately ornamented, a contrast to the simple huts of the villagers who toiled up the hill to it. We may conceive its appearance from the sketch made about 1850 of the gateway to the fort of Panhala – not far from Rohida.”

Some days earlier the two hereditary headmen from the village Karanjiya had come to the fort to pay their taxes. The headmen, Balaji Kudhle and Nayakji Kudhle, were accompanied by a Dalit (lower-caste) servant named Gondnak who was employed by the tax office. Maybe he had been sent to summon them? While in the fort, Gondnak (so the document says) got into a broil and beat up a junior treasury official. The headmen seem to have quickly fled back to their village, but a cavalry unit soon arrived in pursuit and seized their extended families and servants. They then demanded to be fed: the villagers slaughtered a goat and supplied them with rich viands and marijuana candy among other things. After a while, some of the soldiers went to sleep and others sat on guard. But their repast began to tell, and so they summoned the hereditary Dalit (Mahar) servants attached to the village and told them that if even a single detainee was missing in the morning, all of their heads would be cut off.

The villagers held a hasty confabulation: they asked the Dalits who had patrimonial rights in the village if one of them would step forward to confess to the offense: each of these replied – “Confess and have our heads and our sons’ heads cut off? We cannot do this.” The Gondnak who had gone to the fort that day was found and the headmen and their kinsmen beseeched him to surrender and redeem all of them. He had no patrimony and was merely a servant at the fort. He said: “Very well, I will ransom you all with my neck. But swear to me now what share of inheritance you will give my son and swear on your ancestors that you will fulfill that promise.” So they all duly swore to give his son, Arajnak, an eighth share of the rights and fees pertaining to the Dalit Mahar servants of the village as well as an honorific role in village ceremonies and shares in taxable and tax-free lands. They swore this on their ancestors and the name of the fearsome god Mahakala. They bound their descendants to never contest this claim in future. Then Gondnak stepped forward and was taken away and beheaded.

Thus it was that the village delegation came up to the fort to have the deed attesting the creation of a new share in patrimonial rights and lands of the village attested and recorded in the fort where they paid their revenue. The officials in the fort asked the head of the current holders of village service shares, Dhaknak, son of Jannak if he accepted the arrangement. He said that the promise the headmen made bound him and his clan in perpetuity. A deed recounting the circumstances in which Arajnak gained a share in the patrimony was written out and sealed. Copies were kept in the district office and the original given to Arajnak, son of Gondnak to hold as evidence of his rights.

My narrative so far follows that in the document. But I suspect that the village heads may have been the instigators or indeed participants in the broil where the official was beaten up and that the impoverished Dalit Gondnak was the scapegoat for the whole affair. Else it would be unclear why the headmen and their relatives were arrested at the outset. Surely the horsemen would have sought out Gondnak’s kin or children for reprisals? But the incident is a vivid illustration of how important acceptance into the village community was – even if only as a lowly watchman and servant, in western India a few centuries ago.

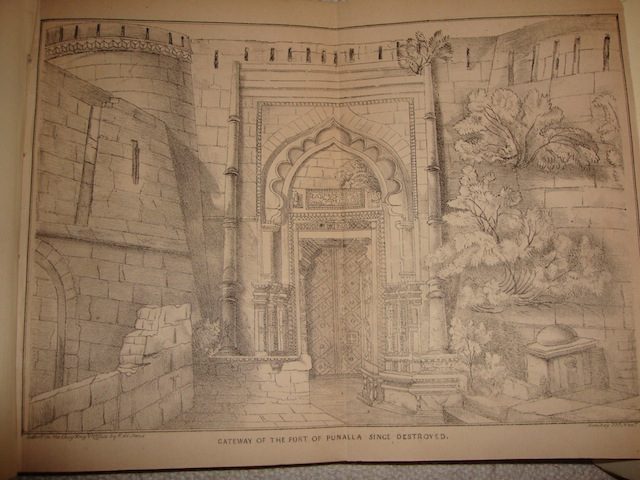

The fort is now in ruins but a gateway – perhaps even the one through which the villagers came – survives largely undamaged.

For more on the social and political system where this incident occurred:

Sumit Guha Beyond Caste: Power and Identity in South Asia, Past and Present (2013)

First image via Graham, D.C. 1854. Statistical Report on the Principality of Kolhapoor Selection from the Records of the government of Bombay No. VIII (new series) Bombay: Education Society Press.

Second Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Third image via Wikimapia.org