By Susan Deans-Smith (Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin) and John W. Smith (Independent Scholar, University Affiliate Research Fellow-Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies)

This article is the first of two parts in a series entitled, Hidden in Plain Sight: Reflections On A Mexican Baroque Enigma. You can read the second part here.

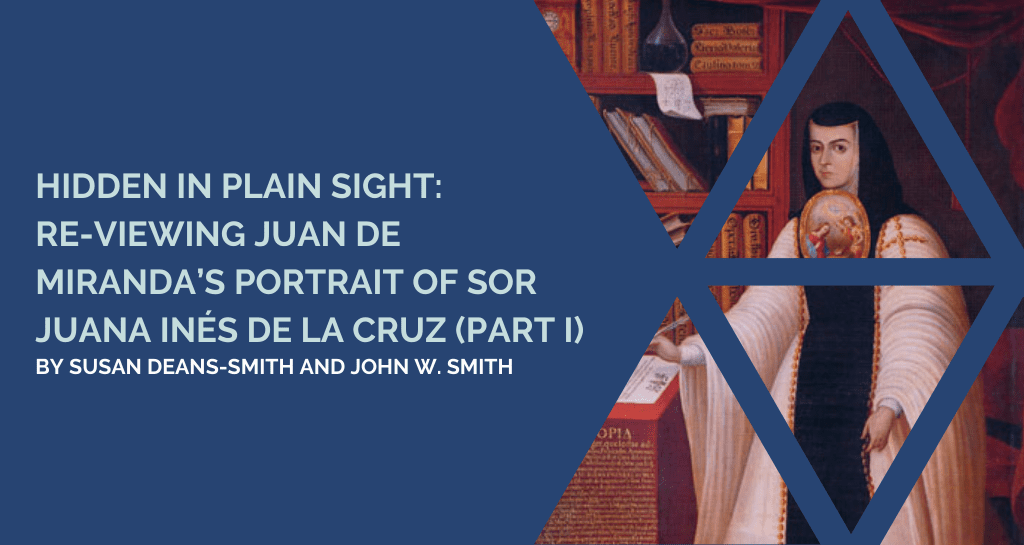

Hidden in Plain Sight is a short book that reassesses the first known full length extant portrait (c. 1700) by Juan de Miranda (c.1667?-1714) of the acclaimed Mexican nun and poet, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (c.1648?-1695) (fig. 1). The life-size portrait (75.19 x 48.42 inches) currently hangs in the rectoría of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Standing at her writing table in her library-cell of the convent of San Jerónimo in Mexico City, the portrait includes a biographical inscription that appears on the side of her desk, a sonnet, Verde embeleso, that Sor Juana appears to have just finished composing, as well as the three published volumes of her work that appear behind the inkwells. Scholars have approached the portrait from varying perspectives and provide valuable insights into different aspects of its creation and interpretation: some, less enthusiastic about the portrait’s aesthetic merits, nevertheless acknowledge its importance as a prototype for subsequent portraits of Sor Juana; others debate how the artist navigates the spiritual and worldly personas of Sor Juana and the tensions between the two. There appears, however, to be a strong consensus about the unusual composition of Miranda’s portrait since it does not employ the conventional iconography associated with portraits of female religious. Rather, Miranda’s portrait is more “reminiscent of…portraits of male prelates and literary figures” (Burke, 1990, 354), influenced by Spanish Hapsburg court portraiture. We are left with the impression of its “bewildering singularity” (Perry, 2012, 7). It is this “bewildering singularity” that requires deeper reflection and is the focus of our study. Interpretation of the portrait has also been complicated by the fact that it is signed by Miranda but it is not dated. Evidence of a second “lost” inscription that identifies both patron and a date of 1713 has added uncertainty as to which date to attribute to the undated extant portrait as well as its patron’s identity: “Mother María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio, her [spiritual] daughter and Accountant, gave this portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz to the Accounting Office of our convent. Year of 1713” (González Obregón, 1900). As such, depending on who you read on the matter (usually very reputable sources), the extant portrait may or may not be dated 1713 and authors may or may not assume the patron’s identity. Confusion is understandable. Scholars have largely discounted suggestions that the second “lost” inscription and date originally appeared on the extant portrait but was erased due to damage or faulty restoration (Ruiz Gomar, 2004). An alternative explanation is that Miranda painted a second version of the extant portrait that included two inscriptions – the biographical one and the one that identifies the patron and is dated 1713. The assumption is that if such a portrait ever existed, its whereabouts are currently unknown. Based on the fortunate discovery of two photographs of this lost portrait during our archival and digital research, however, we can confirm that Miranda painted two portraits of Sor Juana. We address this discovery in greater detail in Part 2 of this project’s description.

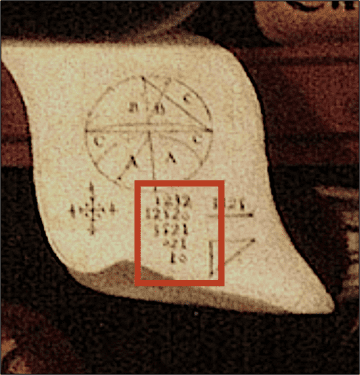

Hidden in Plain Sight is the first study to identify the presence of a hidden enigma in Miranda’s portrait of Sor Juana. In so doing we offer an alternative interpretation and approach to this portrait. We contextualize our study within the broader vibrant cultural and intellectual milieux of late seventeenth-century Mexico City characterized by the Hispanic Baroque with its characteristic embrace of novelty, deception, illusion, exuberance, and spectacle, and which nurtured creative word play, puzzles, anagrams, acrostics, emblems and allegories. It is this cultural context that shaped our working hypothesis that not only are we looking at a commemorative portrait but also at an emblematic portrait of Sor Juana that demands closer reading and questioning. The enigma – hidden in plain sight in the portrait – resides in the white sheet of paper with its notations and numbers (fig. 2). Unlike the large escudo or nun’s badge worn by Sor Juana that depicts The Annunciation, the white sheet of paper and its notations – somewhat surprisingly – have not tempted the curious scholar to examine them more closely.

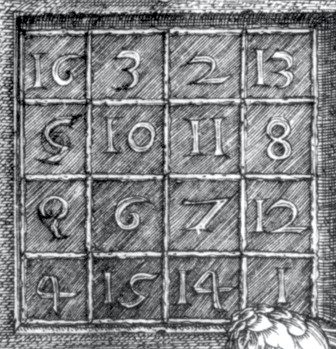

This quietly subversive white sheet of paper is typically characterized as a passive rather than active pictorial element that symbolizes Sor Juana’s interest in science and mathematics (with a nod to her position as the accountant of the convent of San Jerónimo), or it is simply ignored. Octavio Paz, for example, (1988) noted that the five rows of numbers that appear on the white sheet of paper (fig. 3) reminded him of the magic square in Dürer’s Melancholy I (fig. 4) but did not pursue his intuition about their possible significance. So, we pose a simple question: do the numbers and geometric notations on the white sheet of paper in the portrait actually mean something and can they be deciphered? The short answer is yes. We reconstruct how the portrait’s visual elements and sightlines facilitate the engima’s decipherment, comparable to how emblems work but not in a conventional way and provide an analysis of each component of the enigma.

We make several key arguments that provide a new interpretation of Miranda’s portrait. First, to understand the portrait’s unusual composition, it is necessary to recognize the singular importance of the white piece of paper with its furled edge and geometric notations and numbers, anchored by a glass flask containing a liquid (fig. 2). We argue that the notations and numbers represent something much more than a symbolic expression of Sor Juana’s affinity for mathematics and knowledge: when deciphered, they are an active source of information and knowledge about Sor Juana’s birth, life, and death.

Second, given the complexity of the enigma’s construction with the need for precise placement of pictorial elements in the portrait in relation to the white sheet of paper and its notations, we suggest that these particular arrangements constitute an invisible conceptual signature indicative of another participant involved in the portrait’s design, and distinct from the artist’s visible signature that appears on the lower left of the portrait, “Miranda fecit.” What we mean by “conceptual signature” is unmistakable evidence of the application and use of particularly specialized knowledge and expertise evident in the enigma’s construction and which few individuals at the time would have possessed. It is highly unlikely that Miranda, or even the most learned painter versed in emblematic and allegorical compositions, could have created the enigma. We emphasize that our speculations about possible authors of the enigma’s construction occurred after we had deciphered the enigma, not before. It was only after the painstaking process of decipherment that the range of expertise became evident. We suggest that the most plausible candidate was Sor Juana’s friend, mentor and colleague, the creole polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700). A former Jesuit, he held the chair of astrology and mathematics at the University of Mexico, served as the cosmographer of New Spain, conducted astronomical observations, compiled annual almanacs, and amassed a significant collection of pre-Hispanic and early colonial codices and calendars. We argue that Sigüenza drew on his deep knowledge of the devices and various word-image games at which both he and Sor Juana excelled and reveled in – ciphers, anagrams, allegories, and emblems – as well as his mastery of multiple calendrical systems, in order to construct the enigma within the portrait. We posit that Sigüenza’s design for the enigma represents a sui generis hybrid form of an emblematic construct. His deep engagement with the Baroque aesthetics of late seventeenth-century Mexico as well as his experience with allegory and emblem design provide compelling and plausible evidence for his participation in the portrait’s creation with Miranda. Undoubtedly there were other members of Mexico City’s cosmopolitan literati who would have been knowledgeable in multiple areas such as mathematics, astronomy, theology, and games of wit and invention. None, however, unlike Sigüenza, would have possessed the levels of expertise in all of those areas, as well as being conversant with the intricacies of the multiple calendrical systems required to create the complex enigma, including that of the pre-Hispanic Mexican calendar. There is also ample evidence that Sigüenza possessed first-hand experience of working directly with some of Mexico City’s painters, most notably in the crafting of the emblems he designed for the triumphal arch for the entry of the new viceroy to Mexico City in 1680.

Third, we argue that the unusual iconography of Sor Juana’s portrait may be explained in part by our speculations about Sigüenza’s involvement and interactions with Miranda. The placement of the white piece of paper and its notations and numbers, the clustering and specific placement of books – central to an effective decipherment – required a very precise construction which, in turn, affected the positioning of Sor Juana. We speculate that Sigüenza provided Miranda with a detailed schematic that outlined the visual framing for the enigma’s inclusion, in much the same way that he provided designs to painters in 1680 for the emblems he created for his triumphal arch. As such, Miranda would have needed to work with Sigüenza’s schematic to create the portrait.

Fourth, with regard to the extant portrait’s patron and commission we have found no documents that provide details about either of them. It is more than likely, however, that the convent of San Jerónimo was actively involved in the commission, especially since the sonnet that appears in the portrait was given to Sor Juana’s “spiritual daughter,” Sister María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio (1670-1737) (Andrade, 1899) who would commission the second version of the portrait in 1713. Given the extant portrait’s subject matter, we suggest that it was commissioned to commemorate both the fifth anniversary of Sor Juana’s death in 1695, and to celebrate the publication of her third volume, Fama y obras póstumas, in 1700 in Madrid. Emphasis on her literary work in the portrait noted in the biographical inscription and visually evident in the depiction of her published three volumes and the legible unpublished sonnet on her writing table that is effectively “printed” on the canvas is unmistakeable. If we return to the idea of the portrait’s “bewildering singularity,” the composition would not have been straightforward unlike that of profession and conventual portraits with their formulaic characteristics. Given Sigüenza’s established friendship and collaborations with Sor Juana, his frequent visits to the convent (he also composed her funeral elegy), as well as his reputation, and connections at court, it is plausible that the convent sought his advice with regard to both prospective artist and the portrait’s composition. We do not know if Miranda was the patron’s first choice, or an alternative to more prestigious painters who declined the commission or were too expensive. Given the opportunity to work with the painter on such a commission, we speculate that Sigüenza may have used it to create a private tribute in the form of a hidden enigma to Sor Juana in honor of their past collaborations and mutual intellectual interests.

Fifth, our decipherment of the portrait’s enigma contributes to the debate over Sor Juana’s birth and baptism dates by providing alternative dates with those currently proposed: November 12, 1648 or November 12, 1651 (birth dates) and December 2, 1648 (baptism). We assess the credibility of the information provided by the enigma’s decipherment and do so based on long-standing scholarly caution that parish records are characterized by their erratic and error-filled record keeping, disorganized filing, and deteriorated condition of many of the records. To evaluate our hypothesis that Sor Juana’s baptism document may have been erroneously recorded we reviewed the baptismal registers of Chimalhuacán for the years 1642-1655 in order to determine levels of anomalous recordings of baptisms. We do not claim that these alternative dates are unequivocally correct. Whoever provided the information may have been mistaken in the same way that the date provided by Sor Juana’s first biographer, Diego Calleja (1638-1725) – 1651 – is now thought by many scholars to be incorrect (Salceda, 1952). Indeed, 1651 appears in the biographical inscription of Sor Juana even as an alternative date is provided by the enigma’s decipherment. Rather, given the unique source and context from which they are derived and the fact that they fall well within a plausible time frame, they should be taken into consideration as a new possible set of dates for Sor Juana’s birthdate and baptism.

Our final reflections focus on the portrait’s broader significance as a cultural artifact of a particular time and place. We assess the enduring influence of Miranda’s portrait with its hidden enigma on subsequent portraits of Sor Juana painted throughout the eighteenth century. Of the many attributes that artists retain, however, the enigma is not one them, beginning with Miranda himself and his second portrait of Sor Juana in 1713.

Continued in part 2

Works Cited:

Abreu Gómez. Ermilo. Iconografía de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. México: Imprenta del Museo Nacional de México, 1934.

Andrade, Vicente de Paula, Ensayo bibliográfico Mexicano del siglo XVII. México: Imprenta del Museo Nacional, 1899, 483-485.

Burke, Marcus. Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Bullfinch Press, 1990.

Chávez, Ezequiel A. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: su vida y su obra (Barcelona: Casa Editorial Araluce, 1931).

González Obregón, Luis. “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” El Renacimiento, 15 April, 1894.

–––– México viejo. (Paris-México: Bouret, 1900).

Flores Aguirre, Jesús. Papel de Poesía, no. 16, January 1944.

–––– “Un retrato de Sor Juana,” Vanguardia, 3 February, 1944, 28, 77bis-78bis.

León, Jesús de. “Este que ves engaño colorido.” In Nací en el mero Saltillo. Crónica personal de figuras, casos y leyendas de mi localidad (siglos XVI-XX) (México: Saltillo Eres Tu. Programa editoral, 2012)

Maza, Francisco de la. “Primer retrato de Sor Juana.” Historia Mexicana 2/1 [5] (July-Sept. 1952): 1-22.

—— Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz ante la Historia. (Biografias antiguas. La Fama de 1700. Noticias de 1667 a 1892). Recopilación de Francisco de la Maza. Revisión de Elias Trabulse. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, 1980.

Paz, Octavio. Sor Juana or the Traps of Faith. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press 1988, trans. by Margaret Sayers Peden.

Perry, Elizabeth. “Sor Juana Fecit: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and the Art of Miniature Painting.” Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 7 (2012): 3-32.

Ruiz Gomar, Rogelio. “Miguel Cabrera. Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” In Donna Pierce, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, Clara Bargellini, Painting a New World. Mexican Art and Life 1521-1821. Denver Art Museum; Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Salceda, Alberto G. “El acta de bautismo de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” Ábside, vol. XVI, (1952): 5-29.

Sánchez Moguel, Antonio,“Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Insigne poetista Hispano-Mejicano.” La Ilustración Española y Americana, 22 October, 1892.

Tapia Méndez, Aureliano. Carta de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz a su confesor. Autodefensa espiritual. Monterrey:Producciones Al Voleo El Troquel, S.A., 1993.

––––– “El autorretrato y los retratos de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” In Memoria del coloquio internacional. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y el pensamiento novohispano 1995. México: Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, 1995, 442-453.