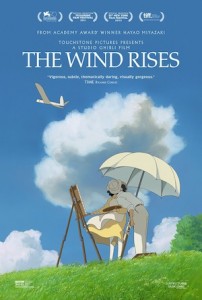

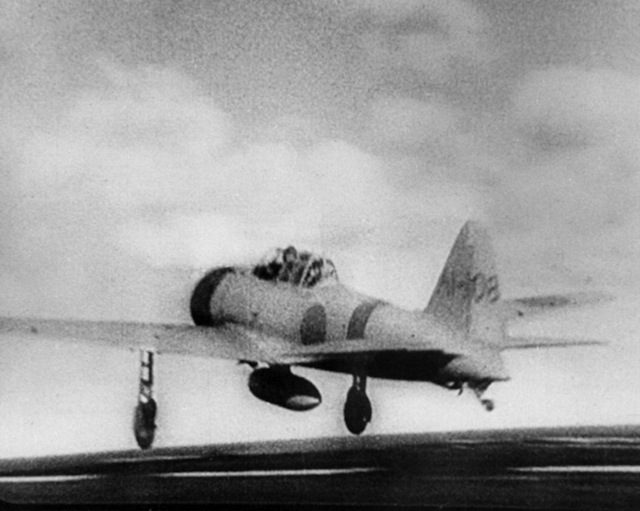

Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli produced many internationally celebrated and beloved animated films, including the award-wining Spirited Away. His farewell masterpiece, The Wind Rises, however, received mixed reactions from international audiences. Viewers who expected to see a fast-paced fantasy like other Miyazaki movies may have been disappointed, because The Wind Rises is a slow-paced historical film. It traces the life of Horikoshi Jiro, an aircraft engineer who invented the famous Zero fighter, which was used by the Japanese navy during WWII. And it chronicles the life of Jiro’s wife, Nahoko, a fictional character from Hori Tatsuo’s acclaimed novel, on which the film is loosely based. Miyazaki describes the tragic fate of the young couple in the maelstrom of prewar Japan.

The Wind Rises vividly depicts Taisho and Showa Japan from the economic hardships in the 1920s through the rise of militarism in the 1930s. Jiro encounters the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 on a locomotive to Tokyo. The magnitude 7.9 earthquake shook the entire metropolitan area, destroying 111,000 buildings. Moreover, since Japanese houses were mostly built of wood, fire spread rapidly, burning down 212,000 residences. As a result, 105,000 people perished, and Japan lost 47% of GNP. Despite Tokyo’s quick recovery, which surprised Jiro’s younger sister Kayo, the earthquake ushered in recurring economic crises. When Jiro arrives in Nagoya to work for an aviation company, he witnesses a run on a local bank, a common phenomenon during the Financial Crisis of 1927, when widespread hysteria precipitated the collapses of 37 banks throughout Japan. While we watch Jiro striving to produce a high-quality fighter aircraft for the army, the Showa Depression hits Japan in 1929. The worst depression in prewar Japan caused severe deflation, financial meltdown, and countless bankruptcies, leaving 2.5 million people unemployed. Meanwhile, thorugh Jiro’s eyes Miyazaki shows us the contradictions in Japan’s ambition to catch up with the West in modern military technology while its people were suffering from the excruciating poverty. “The fact is this poor country pays us [engineers] a lot of money,” Jiro’s colleague Honjo sneers at him, “Embrace the irony.”

Following the so-called Taisho Democracy in the 1920s, symbolized by universal male suffrage, active labor movements, and cooperative diplomacy, militarism engulfed the Japanese society in the 1930s. During this period, Jiro’s romance with Nahoko takes place in the quiet mountains of the Karuizawa resort., A German traveler, Castorp, whose name derives from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, describes the quiet mountains as a shelter from the gloomy atmosphere in Japan caused by the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933, and the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. After his engagement with Nahoko, Jiro becomes extremely busy creating a new fighter aircraft under surveillance of the secret police, as Japan prepares for war with the United States. As tuberculosis, then an almost incurable disease, makes Nahoko increasingly feeble, the young couple decides to get married so that they can spend what little time they have left together. Although Jiro becomes ever more engrossed in the project, Japan’s war machine trumps his dream to craft “a beautiful airplane,” when he develops its ideal blueprint. “The weight becomes the big problem,” Jiro explains to his colleagues, “One solution would be… we could leave out the guns. [The colleagues burst into laughter.] So I decided to put this design back on the shelf.” These lines reflect Miyazaki’s caustic sense of humor.

While most Japanese films about WWII either glorify or demonize prewar Japan, The Wind Rises movingly depicts the era through a personal tragedy of loss and dashed dreams. Not only did Jiro’s beloved wife pass away in solitude, but the war also destroyed his Zero fighter. In early Showa Japan, Jiro’s beautiful airplane was indeed “a cursed dream,” as Italian aircraft designer Geovanni Caproni tells him in the imaginary world they shared. In the final analysis, however, Miyazaki emphasized not only the tragic history but tells a story about how Japan’s youth tried to live in this time, as indicated by his reference to Paul Valery’s poem: Le vent se lève! Il faut tenter de vivre! The wind is rising! We must try to live!

You may also like:

Mark Metzler on Post-War Japan

David A. Conrad’s review of Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II by John Dower (1999)

Images via Wikimedia Commons