When President Lyndon B. Johnson called Thurgood Marshall to offer him the position of Solicitor General of the United States, Johnson reiterated his commitment to doing the job that Abraham Lincoln started by “going all the way” on civil rights, but he warned Marshall that the appointment would cause the Senate to go over him with “a fine tooth comb.” In the July 1965 phone call, Johnson speaks on a wide variety of issues including the image of the United States abroad, the state of the Civil Rights Movement, the importance of “Negro” representation in the justice system, and finally, his thinly veiled, ultimate goal of placing Marshall on the Supreme Court. A monumental historical moment, LBJ’s call to Marshall set in motion a series of events that would culminate in Marshall becoming the first African American Solicitor General and the first African American Supreme Court Justice of the United States.

Thurgood Marshall rose to fame in the 1940s for his work with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, created by Marshall as the legal arm of the NAACP, designed to assault discrimination and segregation. Amassing a huge array of legal victories such as in Smith v. Allwright (1944), Shelby v. Kraemer (1948), and most famously Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), Marshall came to be known as “Mr. Civil Rights.” At the time of Johnson’s call, Marshall was serving on the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, having been appointed in 1961. Johnson, however, had his attentions focused on not just the Civil Rights Movement, but also the growing war in Vietnam. Throughout June and July of 1965, Johnson was forced to consider raising the number of active ground forces and found himself continually at odds with his advisors and the American public. Coupled with the public resignation of the US Ambassador to South Vietnam, Johnson, who often did not want to focus on foreign affairs, found himself facing a series of political and military losses. Johnson hoped to focus his moral idealism and religious convictions on the civil rights struggle, and when told he should de-emphasize civil rights, Johnson remarked, “well, what the hell is the presidency for?”

This recording of the telephone conversation between LBJ and Thurgood Marshall is included in a collection LBJ’s White House telephone conversations made on Dictaphone Dictabelt Records between November 1963 and November 1969. Johnson initially began recording conversations and speeches while in the Senate and continued that practice as President. The recording of presidential meetings and phone calls was first begun by Franklin Delano Roosevelt who aimed to improve consistency in White House public statements and messaging, while also having the option for conclusive proof in the case of false claims made about the administration.

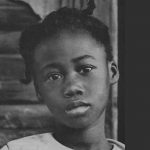

President Johnson meeting with Dr. King and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement (via Wikimedia Commons).

The recording elucidates the tensions Johnson felt between the morality of the Civil Rights Movement and the practicalities of the political climate that he experienced throughout his presidency. Johnson’s actions during the Civil Rights Movement have been a subject of intense study by historians, who seek to understand where the motivations for Johnson’s involvement came from, and how strongly moral and religious principles guided him in comparison with political realities. Randall B. Woods argues that Johnson’s moral and ethical idealism drove both his home front and war front actions, while Sylvia Ellis contends that pragmatism and realism governed Johnson’s racial and foreign policies.[1] Johnson began the phone call to Marshall with an exasperated sigh stating that he has “a very big problem,” which he hopes Marshall will help him with. His tone seems exhausted and his choice to view the appointment as a problem, points to his pragmatism and recognition that the political climate made Marshall’s nomination very challenging. Throughout the call, Johnson never refers to the position as a great honor, but rather an opportunity to raise the character and image of the United States abroad, (he even tells Marshall that he “loses a lot” by taking the position). He seems to view the nomination of Marshall as a duty as well as a politically calculated choice of a “Negro” who is also “a damn good lawyer.” The pragmatic influence takes hold, and Johnson’s political calculations continue to be apparent, as he expresses the difficulties with pushing Marshall’s nomination through Congress, and not wanting to be “clipped from behind.”

Johnson’s comments, however, could be viewed through the lens of morality, rather than pragmatism. His statements about Marshall being a symbol for the “people of the world” could reflect his view that Marshall would be an important beacon of equality across the world. Furthermore, his obvious admiration for Marshall’s political abilities and his strong conviction to back him regardless of what anyone else said, could show Johnson’s commitment to making a decision that reflects his own moral compass. Johnson says that he “doesn’t need any votes” and that he isn’t doing this for the votes, but rather because he wants “justice to be done.” This recording does not solve the debate on Johnson’s ambiguity, but rather continues it, with Johnson’s statements supporting both pragmatism and morality, depending on how one hears the recording.

What is left unsaid is just as interesting. Marshall says very little throughout the conversation. When Johnson describes Marshall as a symbol for “negro representation,” Marshall does not really respond. The question of Marshall’s role as a “race man,” who clearly defines his identity as “black” and seeks to bring about the progression of black people, has been a subject of much debate among historians and legal scholars that is not resolved by this conversation.[2] But this telephone call offers a snapshot of the struggle between practicality and morality would dominate the careers of both Thurgood Marshall and Lyndon Johnson.

![]()

Audio recording of this phone call may be found on Youtube. The original is housed at the LBJ Library: Recording of Telephone Conversation between Lyndon B. Johnson and Thurgood Marshall, July 7, 1965, 1:30 PM, Citation #8307, Recordings of Telephone Conversations – White House Series, Recordings and Transcripts of Conversations and Meetings.

Other Sources:

Wil Haygood, Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination That Changed America (2015).

David Kaiser, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War (2000).

Abe Fortas, “Portrait of a Friend,” in Kenneth W. Thompson, ed., The Johnson Presidency: Twenty Intimate Perspectives of Lyndon B. Johnson (1986).

[1] Randall B. Woods “The Politics of Idealism: Lyndon Johnson, Civil Rights, and Vietnam,” Diplomatic History Volume 31, Issue 1, 2007. Sylvia Ellis, Freedom’s Pragmatist: Lyndon Johnson and Civil Rights, (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2013).

[2] Sheryll D. Cashin “Justice Thurgood Marshall: A Race Man’s Race-Transcending Jurisprudence,” Howard Law Journal, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2009.

![]()

Also by Augusta Dell’Omo on Not Even Past:

Trauma and Recovery, by Judith Herman (1992).

You May Also Like:

Jennifer Eckel reviews the HBO production Thurgood (2011).

Not Even Past contributors provide an overview of the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

![]()