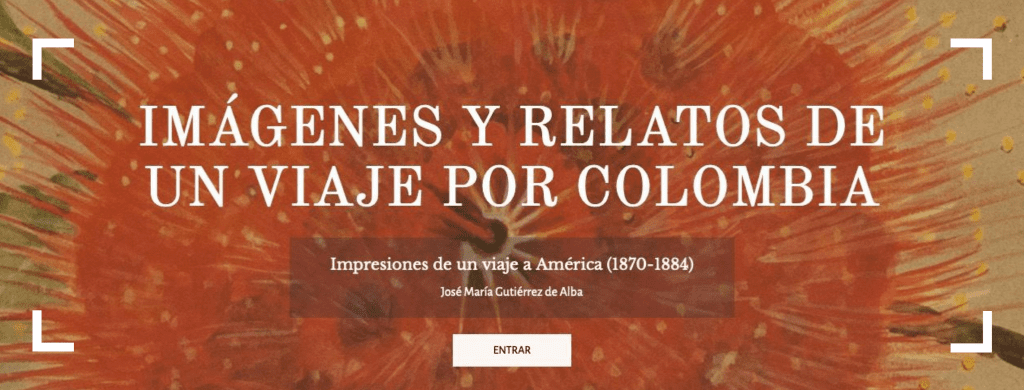

Review of: Imágenes y relatos de un viaje por Colombia [Images and Narratives of a Journey Through Colombia]. Biblioteca Virtual. Banco de la República de Colombia. https://www.banrep.gov.co/impresiones-de-un-viaje/

What was it like for a European to travel and live in nineteenth-century Latin America? Imágenes y relatos de un viaje por Colombia [Images and Narratives of a Journey Through Colombia] offers an exceptional answer to this question. This interactive website features the Colombian travelogue of the Spanish intellectual José María Gutiérrez de Alba, written between 1870 and 1884. A skillful writer passionate about Spanish American affairs, Gutiérrez landed in Colombia as Spain’s diplomatic agent. He was charged with reestablishing relations between the two countries after Colombia’s independence sixty years prior. Nevertheless, his plans were upended. Due to the collapse of monarchy of Amadeo I in Spain and the rise of the First Spanish Republic in 1873, Gutiérrez needed to lie low for a while, and, persuaded by his Colombian friends, he remained in the country. For nearly the next fourteen years, he lived and traveled in Colombia.

Gutiérrez arrived in a country ruled by radical liberals committed to realizing the republican promise of democracy, the separation of church and state, and the erasure of the “colonial legacies.” (1). Astonishingly perceptive, Gutiérrez rapidly began documenting Colombian society. He chronicled how the country was refashioning itself by federalism, unrestricted male citizenship, and a vibrant popular republicanism. He also depicted how the multiple tensions between liberty and order, equality and hierarchy, and unity and diversity unfolded in the radical liberal political project. While living in Colombia, Gutiérrez published political newspapers, agricultural treatises, and literary works. However, his most enduring contribution to Colombia’s intellectual life was his impressive travelogue entitled Impresiones de un viaje a América [Impressions of a Journey to America].

Gutiérrez’s work vividly portrays the political life, popular cultures, and natural landscapes of mid-nineteenth-century Colombia. Through captivating prose, Gutiérrez weaves connections between Colombia’s distinctive regional identities, contrasting topographies, and fragmented economies. With ten hand-written volumes and over 4000 pages, the manuscript comprises the most extensive travelogue ever written about nineteenth-century Colombia. Additionally, its 466 watercolors, drawings, photographs, and lithographs primarily created by the author, constitute the largest graphic collection on the country during the same period.

Bogota’s Luis Ángel Arango Library, which holds these documents, spearheaded the process of cataloguing and digitizing Gutiérrez’s work. Biblioteca Virtual and Makina Editorial—previously named Manuvo Colombia SAS—designed and produced the site. An interdisciplinary team of scholars, led by Juan Pablo Siza, and composed of Efraín Sánchez Cabra, Diana Farley Rodríguez, and Catalina Holguín, researched and curated the collection.

The high-quality digitization of these materials and the ability to quickly download them is a particular strength of the website. All the images are thoroughly identified, catalogued, and accompanied by Gutiérrez’s descriptions. Users can filter the images by thematic categories, authors, and artistic media. The images may also be displayed in the ways Gutiérrez originally organized them.

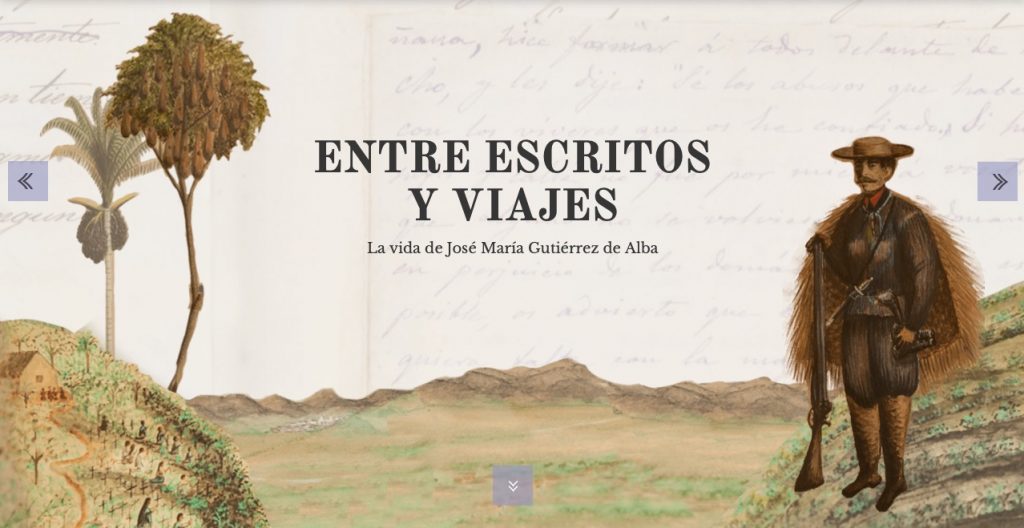

The experience of exploring the manuscript is enriched by an impressive array of visual accompaniments and multimedia resources such as maps, image galleries, infographics, animations, and audios. The overall visual style strikes a fine balance between nineteenth-century and contemporary graphic elements. Hyperlinks are used judiciously, and browsing the site is easy through effective search engines.

Users can approach Gutiérrez’s work through multiple paths: an in-depth historical submersion into the political and scientific contexts of nineteenth-century Colombia; the challenge of traveling through the rugged geography of the country by mule back and steamboat; and Gutiérrez’s political and intellectual adventures. This includes two sections highlighting Gutiérrez’s remarkable commentaries and drawings of the archeological site of San Agustín in southwest Colombia—the largest group of religious monuments and megalithic sculptures in South America—and his depictions of several indigenous peoples in the Amazon.

http://babel.banrepcultural.org/cdm/ref/collection/p17054coll16/id/309

Readers can also recreate in detail eight journeys undertaken by Gutiérrez in various parts of Colombia, as well as his transatlantic crossing and diverse experiences in Puerto Rico, Curaçao, and Venezuela. These expeditions are dissected through georeferenced maps and images of the towns and natural sites visited by Gutiérrez. This section includes various statistics about the trips such as the distance covered, the topics of the illustrations, and Gutiérrez’s companions, both elites and plebeians.

For those who do not have time to dive into Gutiérrez’s travelogue, the site offers the possibility of navigating between 150 selected episodes on a wide range of subjects, for example, amusing anecdotes about hens filled with emeralds in the mining zone of Muzo (2), the fabrication of jipijapa hats (3), political commentaries on the relations between the republican government and the country’s indigenous peoples (4), and the patriotic celebrations of Independence (5). Users can also filter these lively narratives by thematic categories and keywords; even recordings accompany some of them.

Gutiérrez de Alba, José María. Jipijapa hat weavers and sellers. Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia (1875). Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República.

http://babel.banrepcultural.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p17054coll16/id/420/rec/3

To make researching easier, the portal has an entire section that allows searches by different keywords and categories, including text mining tools to determine the frequency and location of the searched words within the manuscript. As a complement, the site offers a comprehensive lexicon of 1200 words created by Gutiérrez, which explain some of the regional idiomatic expressions, local political vocabulary, and scientific names used in the travelogue. Finally, as a way to engage with younger audiences, the project developed an app that creates and sends digital postcards using Gutiérrez’s original illustrations.

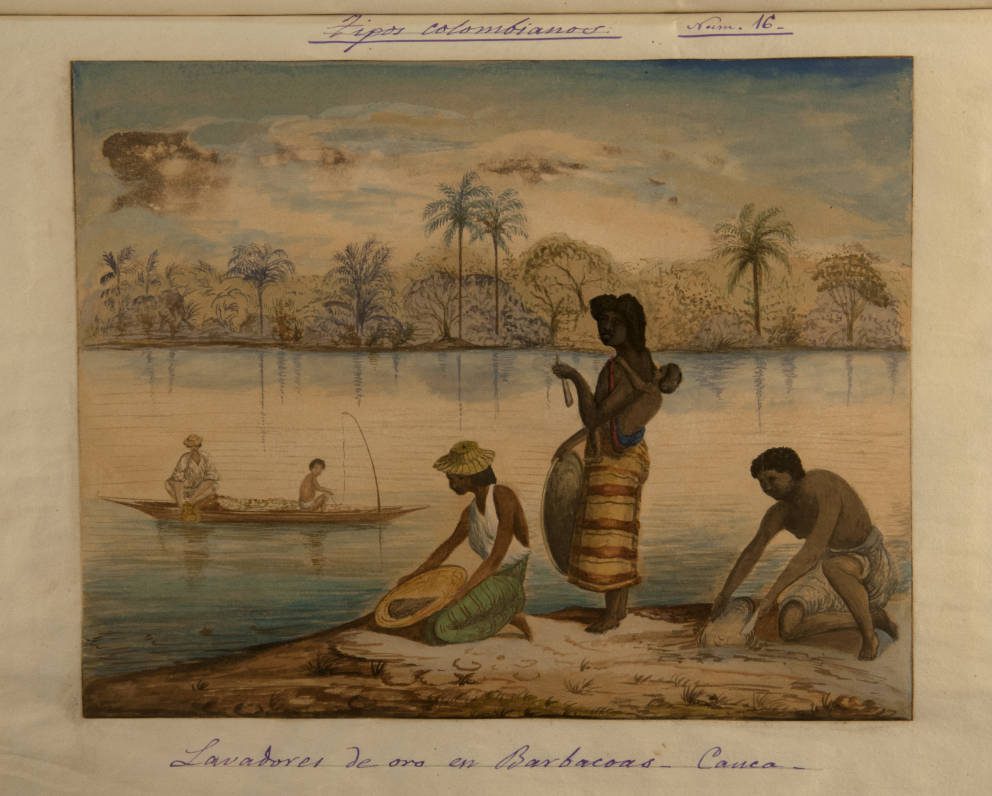

Gutiérrez de Alba, José María. Panning for gold in Barbacoas, Cauca, Colombia (1875). Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República.

http://babel.banrepcultural.org/cdm/sin gleitem/collection/p17054coll16/id/425

The site won a 2017 Digital Humanities Award (6) in the category “Best Use of Digital Humanities for Public Engagement,” in recognition of both its outstanding contribution to the accessibility and usability of online historical materials and the innovative ways to engage with a wide range of audiences, from the relative novice to the more informed reader.

Imágenes y relatos de un viaje por Colombia is a superbly researched project, beautifully written and skillfully designed. It makes a significant contribution to the study of travelogues, popular visual culture, and the language of representation in nineteenth-century Latin America. The exhibit is an inspiring example of what public and digital history can achieve when accomplished with imagination and commitment to archival work. By making Gutiérrez’s travelogue and its stunning visual collection available electronically, this site responds to the ongoing need for quality online resources, both for researchers and the general public. It brings nineteenth-century Latin America history closer under a renewed gaze. It enhances history research and teaching by aiding course assignments and classroom exercises in historical interpretation.

The exhibit covers so many important angles of Gutiérrez’s travelogue that, inevitably, there will be quibbles. For me as a historian, there are two important aspects that deserve more attention. First, since the site is geared towards both the general public and specialists, it would benefit from a “further reading” section with an updated and multilingual secondary bibliography to guide users interested in delving deeper into the historical problems conveyed by Gutiérrez’s travelogue.

Second, the exhibit surprisingly does not offer further information about the history of Gutiérrez’s manuscript itself. When exploring the site, users learn that the author intended to publish it with all the images as engravings under the title Album of Two Worlds, but we never learn why this enterprise never came to fruition. Users also discover that the travelogue was kept in a private collection until 2013, when the library acquired it after a rigorous assessment of its historic value. However, what happened to the collection after Gutiérrez finished his Colombian adventure and went back to Spain?

Information about how Gutiérrez created the manuscript is also missing. Readers never learn, for example, Gutiérrez’s process of record keeping, writing drafts, and drawing during his journeys. Although all the images are carefully catalogued, there is no accompanying data about the materiality of the manuscript—from paper, ink, and paint to annotations and marginalia. An exploration of Gutiérrez’s experiences in producing the travelogue not only would help us better understand its history as an object of material culture but also provide insight into the period’s intellectual culture and practices of knowledge. As this meticulous online exhibit continuously reminds us, archives have social lives and historical itineraries of their own.

(1) https://notevenpast.org/crafting-a-republic-for-the-world-in-19c-colombia/

(2) https://www.banrep.gov.co/impresiones-de-un-viaje/index.php/episodios/view?id=58

(3) https://www.banrep.gov.co/impresiones-de-un-viaje/index.php/episodios/view?id=71&&

(4) https://www.banrep.gov.co/impresiones-de-un-viaje/index.php/episodios/view?id=103&&

(5) https://www.banrep.gov.co/impresiones-de-un-viaje/index.php/episodios/view?id=28