By Aden Knaap, Harvard University

The protagonist-narrator of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 2015 novel The Sympathizer has a thing for squid. (Think less calamari, more American Pie.) The bastard son of a Vietnamese maid and a French priest, he discovers at the age of thirteen that he has a peculiar fetish for masturbating into gutted squid, lovingly—albeit unwittingly—prepared by his mother for the night’s meal. Unfortunately for him, squid are in short supply in working-class Saigon in the late nineteen-fifties, and so he is forced to wash the abused squid and return them to the kitchen to cover up his crime. Sitting down to dinner with his mother late one night, he tucks into one of those very same squid, stuffed and served with a side of ginger-lime sauce. “Some will undoubtedly find this episode obscene,” he concedes. “Not I!” he declares. “Massacre is obscene. Torture is obscene. Three million dead is obscene. Masturbation, even with an admittedly nonconsensual squid? Not so much.” He should know. By the time he is narrating the novel, he has lived through the Vietnam War as an undercover communist agent in South Vietnam, has sought asylum in America, and is now living as a refugee-cum-spy in Los Angeles.

The protagonist-narrator of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 2015 novel The Sympathizer has a thing for squid. (Think less calamari, more American Pie.) The bastard son of a Vietnamese maid and a French priest, he discovers at the age of thirteen that he has a peculiar fetish for masturbating into gutted squid, lovingly—albeit unwittingly—prepared by his mother for the night’s meal. Unfortunately for him, squid are in short supply in working-class Saigon in the late nineteen-fifties, and so he is forced to wash the abused squid and return them to the kitchen to cover up his crime. Sitting down to dinner with his mother late one night, he tucks into one of those very same squid, stuffed and served with a side of ginger-lime sauce. “Some will undoubtedly find this episode obscene,” he concedes. “Not I!” he declares. “Massacre is obscene. Torture is obscene. Three million dead is obscene. Masturbation, even with an admittedly nonconsensual squid? Not so much.” He should know. By the time he is narrating the novel, he has lived through the Vietnam War as an undercover communist agent in South Vietnam, has sought asylum in America, and is now living as a refugee-cum-spy in Los Angeles.

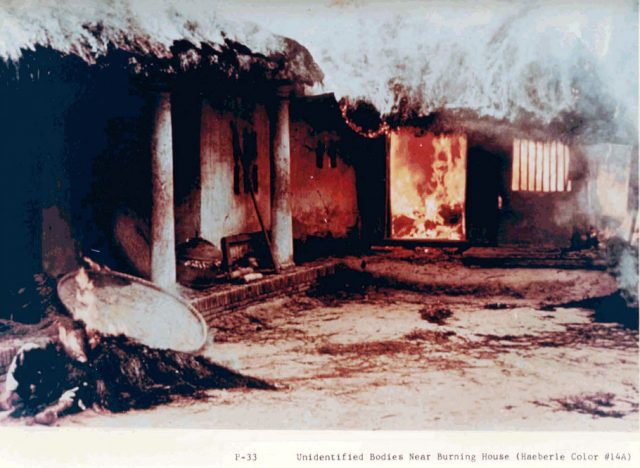

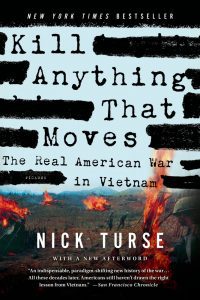

The Sympathizer was published in 2015—three years after Kill Anything that Moves—but it could just as easily have been written as a prompt for historian turned investigative journalist Nick Turse. Indeed, Turse’s central aim in Kill Anything that Moves is to expose the unparalleled obscenity of the Vietnam War: unparalleled both in terms of the devastating scale and variety of harm done and the diabolical levels of premeditation on the part of the U.S. military. Historians of the Vietnam War, as much as the American public, have traditionally remembered the massacre at Mỹ Lai—in which upwards of five hundred unarmed Vietnamese civilians were hacked, mowed down, and violated by the American military—as an outlier in an otherwise largely acceptable war (at least in terms of American actions). But as Vietnam veteran and whistleblower Ron Ridenhour explains, and Turse quotes approvingly, Mỹ Lai “was an operation, not an aberration” (5).

Murder, rape, abuse, arson, arrest, imprisonment, and torture were, in Turse’s words, a “daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam” (6). More than this, they were carried out on orders issued from the uppermost echelons of the American army. They were “the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest level of the military” (6). The outcome? The statistics Turse assembles almost speak for themselves: 58,000 American, 254,000 South Vietnamese, and 1.7 North Vietnamese soldiers dead; 65,000 North Vietnamese and 3.8 million South Vietnamese civilians dead. And these are conservative estimates. Add to that 5.3 million wounded civilians, eleven million refugees, and as many as four million exposed to toxic herbicides like Agent Orange. “[A]ll wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory,” Viet Thanh Nguyen has written in a different context.[1] With Kill Anything, Turse plunges into the fray of this second war, taking aim at staid diplomatic histories that fail to take stock of the purposeful barbarity of the American military’s actions in Vietnam.

Perhaps Turse’s greatest accomplishment in this book is to capture the systematic nature of American wartime savagery. In the Introduction, Turse sets the scene with a series of vignettes, devastating in their unambiguous incrimination of the American military. To take just one of many, an army unit storms a sleepy Vietnamese hamlet occupied by local civilians in February 1968. The captain orders his troops to round up all the civilians. A lieutenant asks what is to be done with them. “Kill anything that moves,” the captain coldly responds.

In the chapters that follow, Turse argues that indiscriminate killing was a deliberate strategy of the U.S. military. Basic training conditions of shock, separation, and physical and psychological stress was intended to break troops down, dehumanize the Vietnamese enemy, and render soldiers amenable to killing without compunction. The Pentagon employed a “system of suffering,” a policy of promoting and rewarding troops based on their “body counts.” In the most blisteringly effective section of the book, Turse chronicles the fate of two South Vietnamese provinces over the course of three years. Turse explores the specific effects of widespread bombing and military rule on urban areas in South Vietnam like Saigon, Da Nang, and Qui Nhơn. He spotlights the actions of a single general—Julian Ewell, known as the Butcher of the Delta—whose demand for bodies from his troops led to the mass murder of close to 11,000 mostly civilian Vietnamese in a single operation. He also explores governmental cover-ups of American war crimes and the distortion of public perceptions of the war.

Accusations against Turse of leftist partisanship, of “imbalanced” treatment of American atrocities, and the use of “uncorroborated” source material miss the point. Kill Anything is self-consciously iconoclastic.[2] Turse takes as his target two hallowed American institutions and traditions—the U.S. military and the idea of American exceptionalism—and turns them on their heads. In Turse’s hands, the organized brutality of the American military in Vietnam becomes the very source of American exceptionalism. In order to do this, Turse relies partly on the U.S. military’s own records and reports, most notably that of the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group: a Department of Defense task force that catalogued more than three hundred substantiated atrocities, dismissing hundreds more as unfounded. Turse adds flesh to the bones of this governmental archive by amassing an unofficial oral archive, the product of interviews he conducted with American army veterans as well as Vietnamese survivors and their descendants from across Vietnam. Accessing this oral history—a history that frequently stands in contention to the official record, Turse is at pains to point out—lets Turse trace the reverberations of violence from small Vietnamese villages to large urban centers, all the way back to the American military command at the Pentagon. In this way, the deep roots of American cruelty in Vietnam are laid bare.

But if Turse’s greatest achievement is to reveal the systematic character of American war crimes in Vietnam, he fails to apply the same organizing principle to the American antiwar effort. Turse is clearly aware of the existence of the antiwar movement: his footnotes are littered with references to exposés they published and uncovered. And Turse devotes much of the introduction and conclusion to singling out individual whistleblowers like Jamie Henry, who risked their lives, families, careers, and mental and physical health in speaking out against American atrocities in Vietnam. By isolating individual whistleblowers, however, Turse ignores the collective nature and effectiveness of the American antiwar movement, that coordinated attacks on the military, liaised with the media, and shielded informants. “Buried in forgotten U.S. government archives, locked away in the memories of atrocity survivors, the real American war in Vietnam has all but vanished from public consciousness,” Turse laments. But it was the antiwar movement that first brought American war crimes in Vietnam to public attention.

More concerning still is Turse’s uncritical assumption of an overwhelmingly U.S.-centric vantage point. In the pages of Killing Anything that Moves, we meet a diverse cast of American soldiers and medics, statesmen and lawyers, protestors and patriots. The book itself opens and closes with Jamie Henry, a former U.S. army medic who returned from Vietnam bent on bringing attention to the atrocities committed by his unit. Even as Turse denounces America, however, he places Americans firmly at the heart of the narrative. Some Vietnamese civilians are given space to speak, but the vast majority are raped, stabbed, shot, bombed, and left for dead. Soldiers from South Vietnam, North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front remain largely absent from the text, hovering around the edges but never taking center stage. But Turse, by his own admission, conducted numerous interviews with survivors in Vietnam. And anyway, what could be more affecting than the testimonies of America’s Vietnamese victims themselves? There is a way in which the marginalization of Vietnamese voices itself enacts a kind of violence: a silencing and an erasure. It turns a story of Vietnamese victimhood into one of American guilt. War wounds run deep, and while Turse expertly attends to some, he leaves others untreated. The war in Vietnam awaits its Vietnamese sympathizer, in all his squid-fucking glory.

Nick Turse, Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (Picador: New York, 2013).

![]()

[1] Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 4.

[2] Gary Kulik and Peter Zinoman, “Misrepresenting Atrocities: Kill Anything that Moves and the Continuing Distortions of the War in Vietnam,” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review No. 12 (2014), 162-198; Gary Kulik, “The War in Vietnam: Version 2.0,” History News Network (2015), < http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/158645>.

![]()

You may also like:

Changing Course in Vietnam — or Not.

A War with Ourselves: How the Media Affected the Vietnam War.

50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War from a Vietnamese American Perspective.

![]()