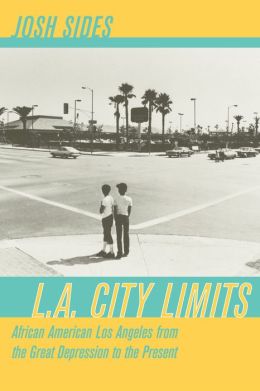

For African Americans in the twentieth century, Los Angeles was a dream destination; black migrants were drawn to it (much as they were drawn to Chicago and Detroit) in search of freedom from the Jim Crow South. However, Los Angeles African Americans quickly confronted their limitations as a minority group. Jobs, housing, education, and political representation spearheaded blacks’ struggles for greater equality in Los Angeles. In L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present, Josh Sides argues that the migratory experience of blacks in Los Angeles was more representative of the history of urban America than that of northeastern cities such as Chicago and Detroit.

Sides begins L.A. City Limits by introducing the Great Migration from the early 1900s through the 1930s, as African Americans migrated from Louisiana and Texas. He explores the growth, development, and sustainment of the Los Angeles African American community as compared to the nation as a whole, both in the north and the south. Sides highlights the roles of Leon Washington and Loren Miller as members of the black press, and the significance of the color line in the labor industry as it applied to blacks and Mexican Americans. He discusses the complex nature of racial equality and organized labor among blacks and Mexican Americans. He also uses several examples that emphasize the separation of the races; not along ethnic lines, but rather to the extent of “white” and “non-white.” As Sides notes, “Multicultural neighborhoods brought blacks and other groups into contact with one another not just as neighbors but also, at times, as fellow parishioners, club members, consumers, friends, and even spouses.” Although Los Angeles African Americans did not live in all-black neighborhoods like in Chicago and Detroit, they still struggled to define their status and “were justifiably ambivalent about their progress” prior to World War II.

Sides begins L.A. City Limits by introducing the Great Migration from the early 1900s through the 1930s, as African Americans migrated from Louisiana and Texas. He explores the growth, development, and sustainment of the Los Angeles African American community as compared to the nation as a whole, both in the north and the south. Sides highlights the roles of Leon Washington and Loren Miller as members of the black press, and the significance of the color line in the labor industry as it applied to blacks and Mexican Americans. He discusses the complex nature of racial equality and organized labor among blacks and Mexican Americans. He also uses several examples that emphasize the separation of the races; not along ethnic lines, but rather to the extent of “white” and “non-white.” As Sides notes, “Multicultural neighborhoods brought blacks and other groups into contact with one another not just as neighbors but also, at times, as fellow parishioners, club members, consumers, friends, and even spouses.” Although Los Angeles African Americans did not live in all-black neighborhoods like in Chicago and Detroit, they still struggled to define their status and “were justifiably ambivalent about their progress” prior to World War II.

World War II was a landmark event for African Americans. Between 1940 and 1970, the black population of Los Angles swelled from 63,744 to nearly 763,000. Sides labels this period as the “Second Great Migration,” and provides case studies of the African American experience from three southern cities: Houston, New Orleans, and Shreveport. He then examines how Los Angeles adjusted to this large influx of black southern migrants, revealing the adverse effects of racial segregation, by highlighting major World War II industry opportunities, the “Negro problem,” and the challenges migrants faced as they settled in South Central Los Angeles.

During the postwar era Los Angeles African Americans experienced a negative restructuring of the postwar economy, as economic parity with whites remained outside their grasp. However, there were advances in employment in major industries such as automobile, rubber, and steel manufacturing. Nevertheless, Sides emphasizes that the aerospace industry, which produced significant suburban residential growth, held to racist hiring practices. Despite these economic and employment limitations, Sides concludes that after World War II, life for black men and women in Los Angeles vastly improved. Housing discrimination during the urban crisis in the postwar era, however, together with “ghetto flight” and the emergence of a black middle class widened the gap among blacks, both financially and geographically. In addition, Mexican Americans, who at times adopted a “white or near white” identity, occupied an area within the racial hierarchy where they were viewed with far more tolerance and acceptance than blacks, according to Sides. This increased Mexican integration into white society was largely a reflection of white attitudes toward blacks and Mexicans.

Sides’s treatment of black political activism illustrates the steps Los Angeles African Americans took in responding to workplace discrimination and police brutality. In his treatment of black activism, Sides examines the signature event of the 1965-Watts Riot and the ideological differences between prominent black organizations, arguing that during the 1940s and 1950s the Communist Party was “the most outspoken and militant advocate for black equality in postwar Los Angeles.”

Sides’s treatment of black political activism illustrates the steps Los Angeles African Americans took in responding to workplace discrimination and police brutality. In his treatment of black activism, Sides examines the signature event of the 1965-Watts Riot and the ideological differences between prominent black organizations, arguing that during the 1940s and 1950s the Communist Party was “the most outspoken and militant advocate for black equality in postwar Los Angeles.”

L.A. City Limits is an important work for students and historians of the American West, race relations, and urban studies. Sides takes a defensive position in his study of the city of Los Angeles in comparison to Chicago and Detroit. He argues that scholarly studies overemphasize the Great Migration to northern cities and a study of Los Angeles provides a more comprehensive view of the overall experience. Sides convincingly constructs the racial hierarchy among minorities, providing an element of Latin American studies that is largely absent from most Great Migration studies. Nevertheless, L.A. City Limits does not completely live up to its title. Sides’s work centers on the years 1945–1964, as opposed to the Great Depression to the present. Despite this limitation, Sides’s examination is a suitable companion to works such as Thomas J. Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (1996) and James R. Grossman’s Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (1989).

Photo Credits:

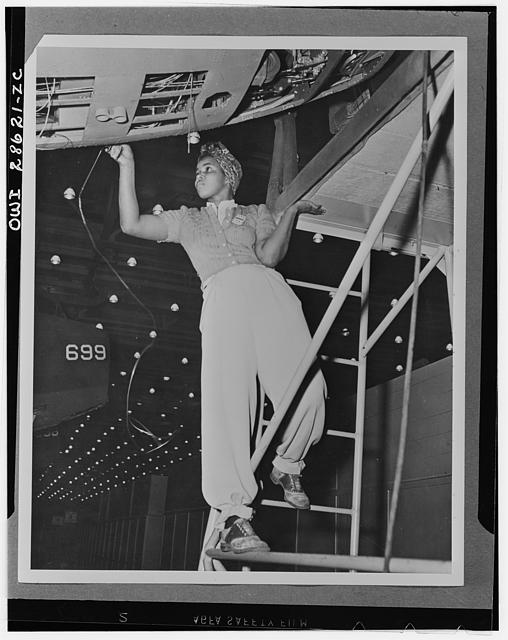

An employee of the Douglas Aircraft Company in Long Beach, CA, circa 1940s (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

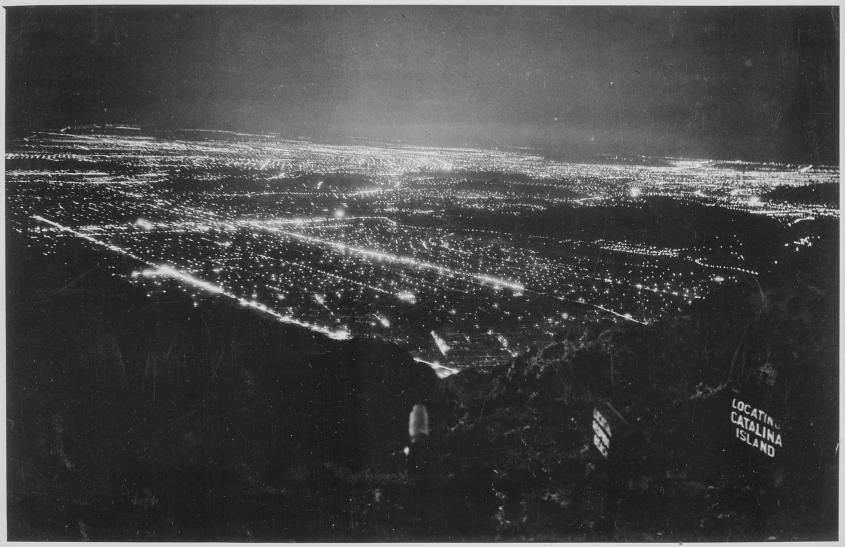

Los Angeles, circa 1950 (Image courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration)