In 1958 Frank Kameny was out of a job. A Harvard trained astronomer and veteran of World War II, he had been working for the Army Map Service. In the wake of the Russian launch of Sputnik in October of 1957, the American government was rushing to catch up, and the young scientist seemed poised to play a role in the new emphasis on space exploration. Yet within just a few months, Kameny’s career was over because he was a homosexual. His story was not unique. He was one of many victims of the Lavender Scare – a manifestation of Cold War paranoia and social bigotry that led to the dismissal of hundreds and possibly thousands of gays and lesbians from government jobs.

In the wake of the Russian launch of Sputnik in October of 1957, the American government was rushing to catch up, and the young scientist seemed poised to play a role in the new emphasis on space exploration. Yet within just a few months, Kameny’s career was over because he was a homosexual. His story was not unique. He was one of many victims of the Lavender Scare – a manifestation of Cold War paranoia and social bigotry that led to the dismissal of hundreds and possibly thousands of gays and lesbians from government jobs.

Historian David K. Johnson sheds light on this forgotten episode in American history. The Lavender Scare grew from the McCarthy persecutions of the 1950s, but Johnson argues that its policies lasted far longer and became more institutionalized than the anti-communist hysteria. The government dismissed homosexuals on the grounds that emotional weakness and the likelihood of blackmail made them security risks. No evidence supported these accusations and medical experts challenged the idea that homosexuals were in any way different from the majority of employees, but to little avail. Executive departments hurried to dismiss employees suspected of homosexuality, lest ambitious congressmen – already suspicious of the expansion of bureaucratic policymaking – target them for public scrutiny. In the midst of the Cold War, fear, politics, and prejudice combined “to conflate homosexuals and communists.”

The Lavender Scare offers an arresting political narrative, but Johnson also makes sure to present the very human face of this drama. Johnson utilizes extensive interviews to demonstrate the way the purges changed the lives of victims and the social milieu of Washington D.C. itself. The rapid growth of the federal government during the Depression and its relatively egalitarian hiring practices attracted large numbers of young people seeking employment, including many homosexuals hoping to escape the limitations of small town life. By 1945, Washington was, in the words of one resident, “a very gay city,” where vibrant communities thrived and authorities tolerated homosexual activity. In an effortless combination of social and political history, the author shows how the rise of the national security state transformed gay Washington, forcing many to leave and others to endure years of joblessness.

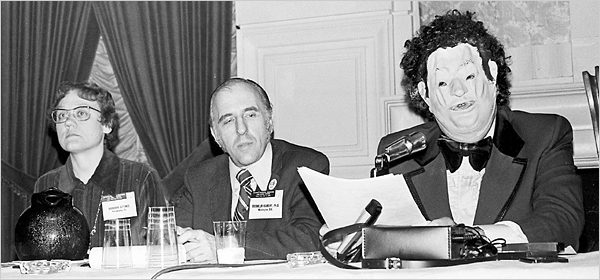

Persecution also inspired a nascent movement in defense of gay lifestyles. Activists like Frank Kameny recast the discrimination against homosexuals as an issue of civil rights. The Mattachine Society of Washington organized picketing and supported challenges to government dismissals, consciously combining “political activism with service to and affirmation of the gay subculture.” Johnson explores how these vocal demands led the government to reevaluate its policies and the connection between the private and public lives of its employees. These early manifestations of homosexual activism not only helped end decades of vocational persecution, but they also informed the networks and tactics that would come to define a movement.

In light of Frank Kameny’s death last October at the age of 86, it is appropriate to look back at the origins of the LGBT activism. The recent repeal of the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy demonstrates that cause of homosexual equality has made great strides, specifically in regard to government service. But at the same time, the continuing debate over the necessity of this policy and calls to reinstate it remind the country that Kameny’s ultimate goals have not yet been achieved. David Johnson’s smart, well-written, and truly engaging book clearly lays out the history of anti-gay sentiment in the modern federal government. It also, perhaps, hints at ways activists can continue to challenge discrimination in the future.

Photo credits:

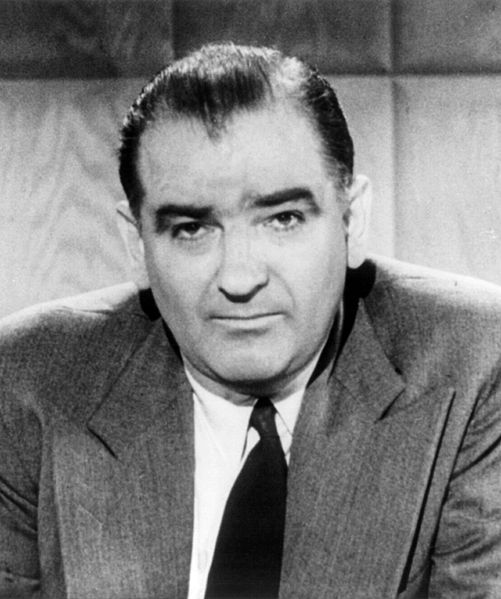

United Press, Joseph Raymond McCarthy, 1954

Library of Commons via Wikimedia Commons

Kay Tobin Lahusen, “Barbara Gittings, Frank Kameny, and John Fryer in disguise as “Dr. H. Anonymous,”” 1972

New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division via Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

Dolph Briscoe’s review of Clint Eastwood’s latest film J. Edgar, about the first director of the F.B.I.