By Dennis Fisher

You wouldn’t think much of the limestone walls hanging on for dear life as you walked along Bluff Springs to get to the grocery store or the bus stop. Not least because they are set back about thirty feet from the road and concealed by trees. I first heard something about the walls and the Sneed mansion they once supported while walking along the Onion Creek greenbelt in South Austin. “The mansion on the hill was built by slave labor,” a local told me.

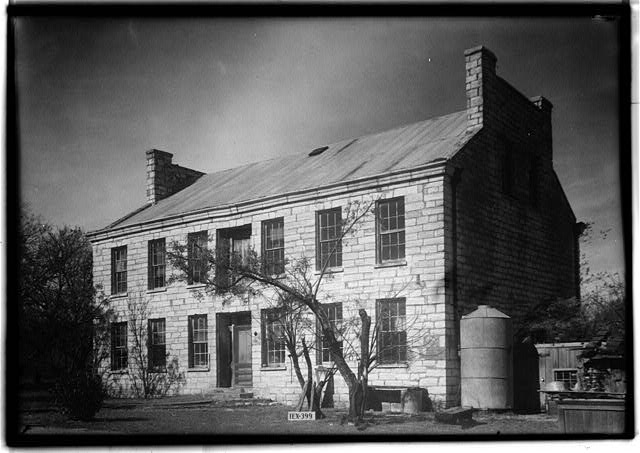

I decided to explore for myself on a recent drizzly Sunday. The entire neighborhood, mostly apartment complexes, a few empty lots, and bus stops, has grown up around this small patch of land, which has been just barely “preserved” (given its dilapidated state) by city officials. Walking past the crumbling walls of the Sneed mansion, marked by graffiti and littered with plastic bottles, evokes not only Austin’s past but also a sense of loneliness.

A 1936 photograph of the Sneed House still intact taken by the Historic American Buildings Survey (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Sebron Sneed Sr. was born in Kentucky in 1802. He spent his early years bouncing around—first in the Missouri militia in 1823 and later in Arkansas practicing law. He married Marinda Atkins of Tennessee in 1824 and they both ended up in Austin, Texas in 1848 after the conclusion of the War on Mexico, making a new home for themselves. They both joined the Pleasant Hill Baptist Church—which still stands today on William Cannon across IH-35. Sebron started the local Democratic Party chapter in 1857. It’s probably not too hard to discern what the Sneed family thought about Texas in the 1850s. Coming from the Appalachian borderlands into newly conquered territory they probably hoped to prosper in a land that would soon expell its Native inhabitants—Tonkawa, Apache, and Comanche peoples around here—and in a place where black slavery was firmly entrenched and outside of the reach of the troublesome former Mexican government as well as the current Federal one—up until 1861, that is, when Lincoln was elected to the presidency. Sebron Sneed Sr. owned 21 people as property in 1860. One of them, Nancy Jane, was purchased by Sneed as “the highest bidder . . . of a certain mulato girl” in Arkansas in 1848 just before he relocated to Texas. We have no idea what Nancy Jane, almost entirely lost to us in the historical record, must have thought, felt, and dreaded–torn from her relatives and brought to a strange land.

Daguerreotype of Marinda Atkins (1809-1878), wife of Sebron Sneed, ca. 1849-1850 (Image courtesy of Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library)

The location chosen for Sneed’s mansion still makes good sense. It stands on a hill that lifts slightly to the west but then drops down to where IH-35 currently sits. The land gently slopes downward on all remaining sides. Close by on the north and east sides of the house wind small streams that gently make their way downhill. Limestone, soft and porous, is readily available in this area. All of south Texas (and extending down into Guatemala and Belize) was covered by a shallow sea some sixty million years ago, which left behind as its primary legacy a thick layer of limestone—great for building houses and pyramids as well as collecting and channeling water into natural wells, creeks, and aquifers.

Sneed made his money in the legal profession. His papers, located at the Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas, are full of promissory notes from clients. In 1860, he paid fifty dollars in “occupation taxes” as a lawyer. By looking at his tax receipts we find that he owned enslaved people, horses, cattle, and land in Del Valle (just east on Highway 290)—the numbers vary from year to year suggesting he sold people as well. In 1864, he paid his county taxes in kind with 545 bushels of corn. During the war he made money by selling two enslaved men—Peter and Isaac—to Confederate General Magruder for building fortifications at Galveston. If Sebron saw Texas as a promised land, his vision and future rested firmly on the foundation of white supremacy. Furthering that vision, Sneed opened his mansion in south Austin as a recruiting station at the outset of the Civil War and later as a convalescent home for returning wounded soldiers. Both he and his son fought in the war—he as a provost marshall and his son as a captain. Sebron Sr. would die in 1879, at the time engaged in “agricultural pursuits”—the records shed little light on this post-war aspect of his life. He would be buried in the adjoining family cemetery along with his wife, other family members, and “infant Sneed.” After the war, his son moved downtown to Colorado and 3rd and kept busy as a lawyer, acting Comptroller, and later as superintendent of Travis County schools.

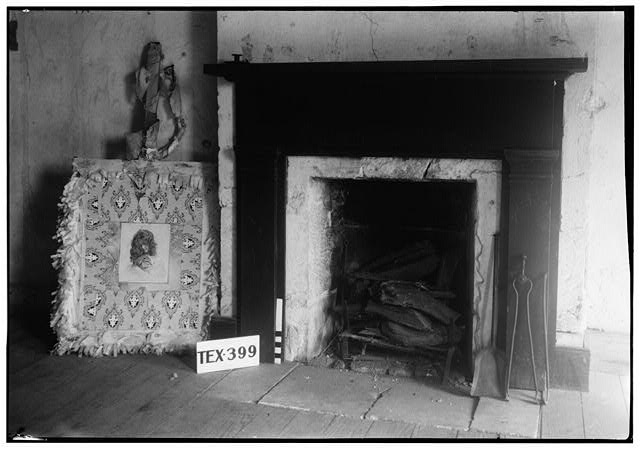

Second floor fireplace of the Sneed House, 1936 (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Today echoes of that era linger in both small and not so subtle ways. Ranch owners along the Onion Creek greenbelt still regularly take their horses out along the trails and locals flock to McKinney Falls to play along the limestone and creeks that crisscross the area. Confederate flags still find a place at rallies at the capitol as well as on t-shirts and pickup trucks. But today south Austin at William Cannon and IH-35 looks very different. Anglo-Americans, African-Americans, Native-Americans, Mexican-Americans, and Mexicans all call this place home. Hispanic Texans constitute the majority of enrolled students in a state that could swing Democratic in a decade or less in a country that has twice elected an African-American to be president. Looking at what remains of the Sneed mansion serves to remind us of the very different histories that have inhabited these places.

If you’d like to learn more about the Sneed family:

The Sneed House’s city zoning information

A guide to the Briscoe Center’s Sneed family papers

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.