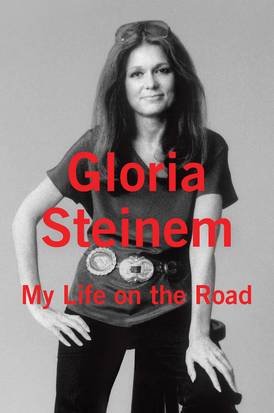

Gloria Steinem’s eighth book is part feminist memoir, part autobiography of personal growth and change, part invocation to the adventure of living in the present, and part story book. Her style is relaxed and conversational but never random or sloppy. She presents four purposes of the book in the Introduction, but I found two recurring themes: the joy of serendipitous discovery while traveling to new places and the value of listening, the power of groups talking and listening, that she learned from the talking circles while in India.

The life on-the-road theme begins as she recalls that until she was ten years old her family spent most of each year travelling around the country as her father bought and sold antiques. Though she longed for a “real home” when she was a child, she is grateful for her father’s “faith in a friendly universe” and credits him with her tolerance for a life of relative insecurity. She writes with sadness about her lonely mother who worked as a journalist before she married. This migrant life ended when her parents divorced and she lived in Toledo with her clinically depressed mother. She went to Smith College on a scholarship—Government major, Phi Beta Kappa—and, then, spent two years in India on a fellowship. She studied at the University of Delhi and spent several months with a Gandhi-inspired group who walked from village to village after terrifying caste riots in east India. The walking group invited villagers to meet with them, and with each other, to share their grievances and to provide reassurance after the riots. She credits this experience with teaching her the value of listening and the amazing things that happen when people share with each other in groups.

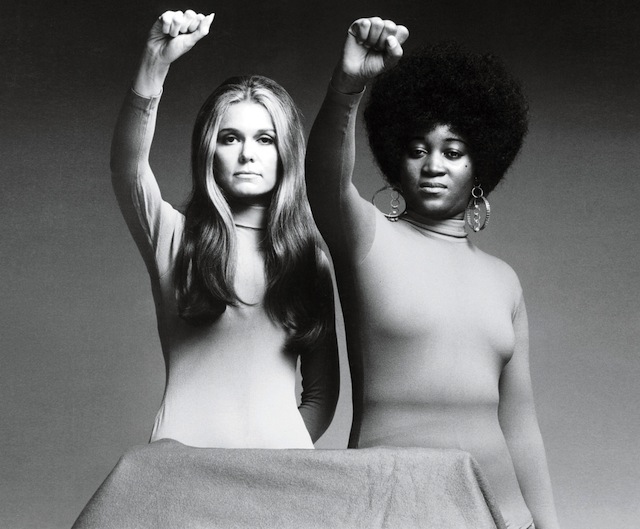

She returned to the U.S. to work as a free-lance journalist and an avid participant in political campaigns, the first being the 1952 Adlai Stevenson campaign for president. She became aware of the women’s rights-women’s liberation movement in the 1960s. In 1971, after New York Magazine published her article “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation,” she began to receive invitations to speak about feminism. Terrified of public speaking, she enlisted the help of her friend Dorothy Pitman. As a bi-racial team, they spoke at community centers, in union halls, and school gyms. As Steinem gained skill and confidence, this duo was soon traveling to college campuses, to meetings of the National Welfare Rights Organization, to speak with United Farm Workers chapters, lesbian groups, and antiwar activists. Steinem saw her job as helping the audiences become “one big talking circle” — there was always discussion after she and Pitman made their presentations. Later, she would work and travel with the inimitable Florynce (Flo) Kennedy.

Most of the stories that Steinem shares are stories from the road as she became “a public speaker and a gatherer of groups” and one of the best-known feminists in the U.S. She refers to these campus speaking engagements as the “largest slice of my traveling pie.” One of her best stories is about the often-tense 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston. This account features Bella Abzug, co-founder of Women Strike for Peace in 1961, three-term Congresswoman from New York, and tireless activist. Abzug, Congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Patsy Mink asked Steinem to help them organize the National Women’s Political Caucus, which they did in 1971 with a diverse group of notable women. There are other stories from the feminist trenches, but this book is only part feminist memoir. There is a curious and very fun chapter titled “Surrealism in Everyday Life,” and there is a chapter about her time in “Indian Country” by which she means her relationships with Native Americans, including Wilma Mankiller, deputy chief of the Cherokee Nation. Speaking of “Indian Country,” I was troubled when she confidently asserted the popular, but erroneous, notion that that the U.S. Constitution was modeled on the Iroquois Confederacy.

Steinem shares these stories in the most-unassuming way as if you were a long-time friends visiting over a cup of coffee after having not seen each other for a while. She talks (writes) about covering Eugene McCarthy after Robert Kennedy’s assassination in 1968 and about the Clinton-Obama contest in 2008. My favorite chapter, “Why I Don’t Drive,” is an account of conversations she has had with taxi drivers. Oh, the stories!

But, of the lessons that she has learned and that she shares, my favorite is this: “One of the simplest paths to deep change is for the less powerful to speak as much as they listen, and for the more powerful to listen as much as they speak.”